Can people power also be successful in defeating the more diffuse evils of oligarchy and corporate rule?

Published in the December 2014 issue of the New Internationalist.

Twenty-five years ago, one of the most decisive and unforeseen waves of grassroots revolt in modern history swept through Eastern Europe. First, in Poland, came the triumph of Solidarity, whose stunning electoral success in 1989 was made possible by nationwide strikes the year before. Then, in Hungary, marches in the spring and summer hastened far-reaching negotiations between government and opposition leaders.

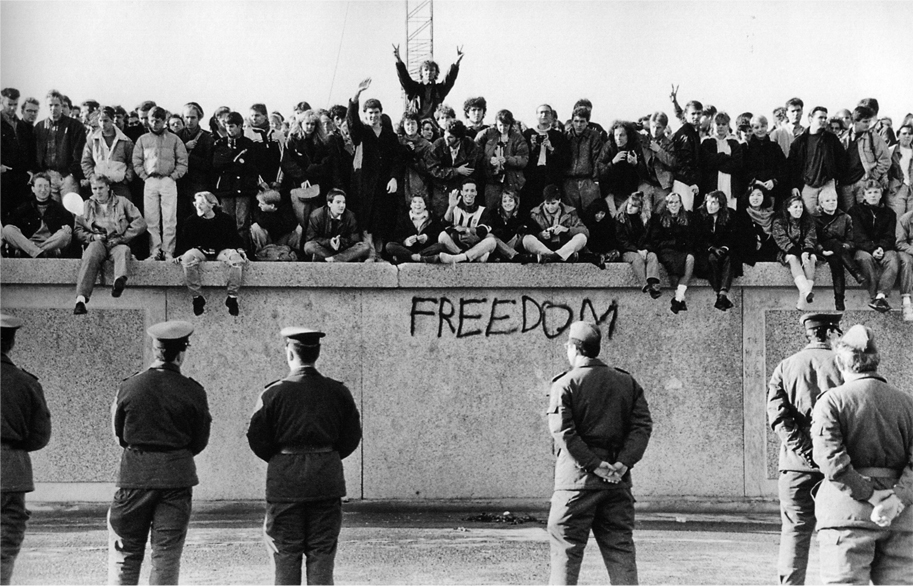

Reforms there prompted a mass exodus of East Germans, who began crossing via Hungary into the West. Those who stayed in the German Democratic Republic grew increasingly vocal in their dissent: Weekly protests in Leipzig spread to Dresden and East Berlin. On November 9, 1989 authorities who had notions of allowing limited passage through the hated Wall found themselves famously overwhelmed by emboldened citizens.

The crowds came bearing pickaxes.

That same month, the bludgeoning of student protestors in Czechoslovakia set off the mass rallies of the Velvet Revolution, which promptly and improbably lifted resistance playwright Vaclav Havel into the country’s presidency.

Few could have imagined that the end of communist rule in Europe would come about neither through nuclear confrontation nor, with rare exception, through military coups—but primarily through the force of civil resistance.

Today, the power of unarmed uprising to topple undemocratic governments has been amply demonstrated. We are now presented with a different question: Can people power also be successful in defeating the more diffuse evils of oligarchy and corporate rule?

The answer depends in no small part on how we understand the history of events such as revolutions of 1989. Because the type of social movements needed to combat climate change and to challenge economic exploitation—movements that are disciplined, daring, and disruptive—must be able to thwart the apathy of historical determinism and spot unexpected possibilities for change.

Many analysts downplay the importance of popular resistance in Eastern Bloc countries. Instead, they focus on the geopolitical forces that set the stage for the Soviet Empire’s collapse. They note the mounting economic crises of state socialism, exacerbated by decades of competition with the West. They stress Mikhail Gorbachev’s signals that he would tolerate reformism and not follow the brutal example set by the Chinese government at Tiananmen, also in 1989.

Certainly, this perspective raises a valid point: social movements do not operate in a vacuum. Modern theories of civil resistance recognize that the success of popular campaigns depends not only on the strategies and skills of activists, but also on political and economic conditions.

The danger is that, in overemphasizing such conditions, political scientists talk as if the sledgehammers that brought down the Berlin Wall wielded themselves. They overlook the creativity and courage that it took to stand up to the Stasi—traits which will be needed in the future if genuine democracy is to win out over the unchecked prerogatives of profit and privilege.

It is important to remember that, like the great bulk of Wall Street analysts on the eve of the 2008 economic crisis, the talking heads of the time were caught utterly off guard by the revolutions of 1989. They assumed that Cold War alignments were firm and downplayed the likelihood of momentous upheavals. Gorbachev’s overtures notwithstanding, one correspondent wrote for the leading journal Foreign Affairs in 1987, “there is no prospect of fundamental change in relations between [Warsaw Pact] countries and the USSR.”

There is a lesson here. We are constantly presented with developments that historians might some day name as critical forces prompting social transformation. We have not seen the end of financial calamities, for one, and we have witnessed just the start of dislocations resulting from global warming. But only with hindsight can we see how history’s varied and unruly forces conspire to turn small, hopeful outbreaks of resistance into epochal uprisings.

Those who rebelled in 1989 did not know how ripe were the opportunities that hung before them. We can be thankful, and inspired, that they nevertheless dared to seize them.

__________

Photo credit: University of Minnesota Institute of Advanced Studies / Public domain.