Technocratic liberals treat movement groups as another “special interest” rather than a central pillar upholding their ability to govern.

Published in the March 2017 issue of the New Internationalist.

In an eloquent farewell speech given ten days before he left office, U.S. President Barack Obama challenged supporters, “If something needs fixing, lace up your shoes and do some organizing.”

For many American progressives, the exhortation brought back the feelings of hope and excitement that Obama once evoked. Back in 2008, the prospect of electing a president with a background in community organizing was a thrilling one.

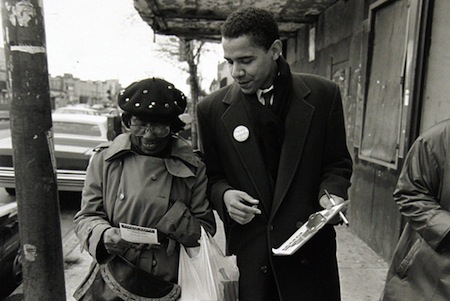

Working on Chicago’s South Side in the 1980s, Obama trained in the organizing lineage of Saul Alinsky, bringing together public housing residents to fight for community improvements. The future president often claimed to have been shaped by the experience, and in some of his strongest rhetorical moments he evoked the power of social movements to force change.

But taking seriously the idea of Obama as an organizer creates a demanding standard for evaluating his legacy. We must ask: Are social movements stronger at the end of his tenure than they were at the beginning?

Unfortunately, by this measure, his presidency falls short.

Compared with the unfolding horror of the Trump administration, there is much to make us feel already nostalgic. Progressives taking stock of Obama’s accomplishments have found both positives—including the extension of health coverage to millions and the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—and negatives—the continuation of extralegal assassination via drone strike and the failure to seriously rein in Wall Street power when finance was most vulnerable. But whatever criticisms we have, the overall thrust of his public policy was infinitely preferable to what we are seeing with Republicans in control.

However, if we use the lens of organizing to evaluate success or failure, it leads to a tougher reckoning of Obama’s time in office.

The fortunes of the labor movement provide a critical bellwether. Under Obama, the percentage of the workforce in unions continued a decades-long decline, falling from 12.4 percent to 11.1 percent. This is distressing because organized labor remains the most important institutionalized power bloc on the American left.

Unfortunately, the politicians who seem most attuned to the vital role of unions are Republicans, who move ruthlessly to curtail union power whenever they can. When conservatives in Kentucky and Missouri assumed power over state government after the November election, their first priority was to push forward so-called “Right to Work” laws, which suppress union membership and hinder efforts to collect dues.

During Obama’s tenure, four new states—including former union strongholds—passed these laws, and others limited the ability of public sector workers to organize. The impact became quickly evident. In Nevada, a state where unions, led by hotel and restaurant workers, have been strong, Hillary Clinton carried a hotly contested election. In contrast, in Michigan and Wisconsin, places where right-wing legislation has hit labor hard, Trump defied polls and won.

While their conservative adversaries understand the nature of power, technocratic liberals treat movement groups as just another “special interest” rather than a central pillar upholding their ability to govern. When Democrats gain majorities, measures to bolster organizing rights are never priorities. And so the party consistently fails to reverse the damage done—let alone to spur labor’s revitalization.

This remained true under Obama. Key union-backed policy proposals languished, while the White House pushed pro-corporate trade deals such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The grassroots drives that did flourish in the Obama era—such as #BlackLivesMatter, the pro-immigrant DREAM Act students, the growing climate movement, and the Fight for $15—encountered a White House that could sometimes be cajoled into doing the right thing. But they did not find a genuine champion in office.

In President Obama, social movements had an adversary far preferable to what they will have in Donald Trump. But the dream of having a true organizer in the White House—a president who will see social movement victories as his or her own—remains unrealized.

__________

Photo credit: White House Archives.