Many of the criticisms of microcredit are valid and deserve to be aired, yet the effort to oust Yunus is part of an unwarranted and politically motivated attack.

Published in Dissent.

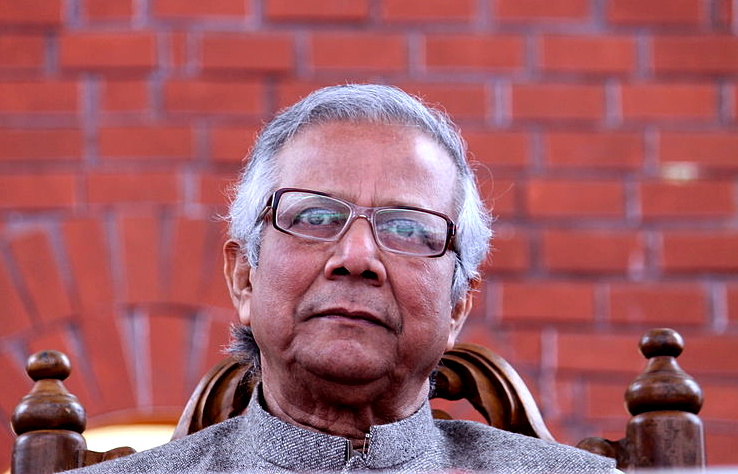

It’s final. Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus has been sacked. This week, Yunus lost his last appeal before the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, ending a two-month legal battle over whether he would be permitted to remain at the helm of the Grameen Bank, the pioneering microcredit institution he founded some thirty years ago.

The battle has drawn attention to some key shortcomings of the microcredit movement, with Yunus’s opponents—including Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina—going on the offensive. The result has been a curious situation. Many of the criticisms of microcredit are valid and deserve to be aired. Yet the effort to oust Yunus is part of an unwarranted and politically motivated attack. Moreover, when it comes to addressing the for-profit cooptation of the microcredit movement, Yunus is one of the good guys.

Officially, Yunus—who is now seventy—is being dismissed for remaining in his post beyond a mandatory retirement age of sixty for bank directors. But Yunus’ age was not an issue until, in 2007, he charged politicians like Sheikh Hasina with corruption and briefly considered forming his own political party. As the Globe and Mail reports:

“He soon backed away from that plan and today he says he wants nothing to do with politics. But many people here believe Sheikh Hasina’s mistrust and anger are unabated, and the allegations against Grameen gave her a convenient opportunity to take out a potential rival.

“Remember that in 2013 the country will again have elections—this is a way to send a message not just to Yunus but to anyone else who might be considering politics,” said Lamia Karim, a Bangladeshi native who teaches at the University of Oregon and has long studied Grameen.”

Karim, who regularly brings a clear and critical perspective to the microcredit debate, has a good article here on “The fall of Muhammad Yunus and its consequences for the women of Grameen Bank.”

Another layer of the recent controversy relates to a Norwegian documentary that aired last fall. It charged that Yunus had improperly redirected some $100 million in aid money from the Grameen Bank to a sister organization. However, a government committee cleared Yunus of charges last month, and there was never any accusation that he had embezzled money or personally profited from the transfer.

With regard to current dispute, I think it is evident that Yunus deserves a defense. There have long been criticisms of his management style—complaints that he is a micromanager and that he hasn’t done enough to cultivate leadership that could succeed him. But those are hardly compelling as critiques of the microcredit movement as a whole. And the age-related rationale for forcing Yunus out is clearly a pretext.

That said, while many of the attacks on Yunus himself are unfair, other criticisms of the microcredit movement that have received attention as a result of his ouster are well-founded. The Guardian mentions several of these:

“Hasina has accused the Grameen Bank and other microfinance institutions of charging high interest rates and ‘sucking blood from the poor borrowers.’

The attacks on Yunus come at a time when microlending—once hailed as a model that would change the lives of hundreds of millions in the developing world—faces increasing hostility from politicians across the region.

In India, politicians have accused bankers of profiting from the poor and, in some places, have banned further lending or recovery of debts. In the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, aggressive selling by scores of unregulated microfinance firms has pushed huge numbers of already desperately poor farmers deeply into debt.”

I wrote a profile of Yunus in the Fall 2009 issue of Dissent, where I described the context of such criticisms:

“Viewed modestly, placed among an assortment of tools for helping the poor, micro-loans can be fruitfully pursued along with other initiatives; in this vein, the progressive governments of Venezuela and Bolivia have each explored options for expanding microcredit as part of their policies for fostering small business. But to the extent that microcredit serves an ideological function—reinforcing the belief that an unrestrained market works to the advantage of even society’s least fortunate—it can prove tragically counterproductive.

….

As microcredit has spread throughout the world, it has spawned a growing faction of practitioners who contend that micro-lending should not be dependent on donations. In order for it to make a really significant impact, they believe, it must be profitable enough to attract private investment. Seeking to tap mainstream capital markets for their work, the bankers in this school prefer to use the term “microfinance” to describe their efforts. The tension between them and the more socially minded, profit-averse “microcredit” institutions now represents a major conflict in the field.

Some predict that the number of microfinance lenders will soon dwarf the number of institutions operating on some version of the Grameen model. The Economist noted in 2005 that, “some of the world’s biggest and wealthiest banks, including Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, HSBC, ING and ABN Amro, are dipping their toes into the water.”

….

[A]s the desire of micro-financiers to turn a profit has come into the picture, a heated debate has emerged over the question: What is an acceptable interest rate to charge the poor?

While microcredit is relatively new, usury is very old. A legion of subprime mortgage brokers, credit card companies, payday lenders, and pawnshops have made amply clear that there is nothing inherently beneficent about lending to those of limited means.

The Grameen Bank’s core loans, according to Yunus, are made at a relatively modest interest rate of 20 percent. Those who have looked critically at the issue argue that, after adding taxes, fees, and mandatory savings deductions, and then measuring annual interest rates using the norms of U.S. banking, even Grameen and other socially driven microcredit bodies regularly deal in loans that charge between 30 and 50 percent interest. With for-profit microfinance institutions, the rates can be much higher. In recent years, reporters for Business Week and the New Yorker have pointed to micro-lenders in Mexico who charge interest between 110 and 120 percent.

Compared with the demands of a loan shark exacting 200 or 300 percent interest, these terms might be considered an improvement. But they strain credibility when presented as instruments of poverty relief.”

In short, microcredit is not necessarily harmful. But when made an extension of neoliberal market fundamentalism, it certainly is.

You wouldn’t know it from his detractors, but Yunus recognizes this. Among major players in the microcredit world, Yunus has been one of the most vocal about denouncing the movement’s profiteers. In January he wrote a fine op-ed in the New York Times entitled, “Sacrificing Microcredit for Megaprofits.” There he argued:

“In the 1970s, when I began working here on what would eventually be called “microcredit,” one of my goals was to eliminate the presence of loan sharks who grow rich by preying on the poor. In 1983, I founded Grameen Bank to provide small loans that people, especially poor women, could use to bring themselves out of poverty. At that time, I never imagined that one day microcredit would give rise to its own breed of loan sharks.

But it has….

To ensure that the small loans would be profitable for their shareholders, [microfinance banks] needed to raise interest rates and engage in aggressive marketing and loan collection. The kind of empathy that had once been shown toward borrowers when the lenders were nonprofits disappeared. The people whom microcredit was supposed to help were being harmed. In India, borrowers came to believe lenders were taking advantage of them, and stopped repaying their loans.

Commercialization has been a terrible wrong turn for microfinance, and it indicates a worrying “mission drift” in the motivation of those lending to the poor. Poverty should be eradicated, not seen as a money-making opportunity.”

It is uncertain what will happen next to Grameen, and whether future changes will end up benefiting the bank’s poor borrowers. But this much is clear: efforts to vilify Yunus should not obscure his very important warning about microfinance’s alarming wrong turns.

__________

Photo credit: Faisal Hasan / Wikimedia Commons.