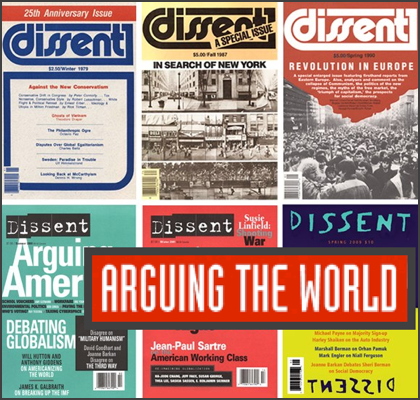

A dispatch for the “Arguing the World” blog at Dissent magazine.

Published in Dissent.

On the far side of the Atlantic, a future Queen of England has been selected. The office of the Prince of Wales announced on November 16 that Prince William, the second in line to the British throne, has become engaged to Kate Middleton, a nice, middle-class young woman who was a college classmate of his at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and whom he has been dating, on and off, for most of the past decade.

Although the term “middle class” has been widely used throughout the British and international press to describe the new princess-to-be, in this instance it means something quite unusual. As it turns out, Middleton’s parents are millionaires, having made a fortune from a small party-planning business they started. True, her mother once worked as an airline stewardess and her father as a flight dispatcher. But Middleton’s upbringing was decidedly privileged. For one, she attended high school at an elite £30,000-per-year academy. (That’s tuition and fees of about $48,000 per year at current exchange rates.)

Nevertheless, since Middleton has no aristocratic family pedigree, she is, in England, considered just a middling commoner. It is a fact absurd enough to move even the Economist to comment.

In the United States we have no formal aristocracy, but we have plenty of class absurdities of our own. In some ways, it might be even harder here to escape the reach of the “middle class.”

Whether you’re making an income just north of the poverty line or you’re bumping elbows with the nation’s most fortunate, chances are that America’s “middle class” can accommodate you within its incredibly elastic walls. After all, even Bill Gates could be considered just your average suburban computer geek made good, and Warren Buffett just a meat-and-potatoes guy from Omaha who once worked in his grandfather’s grocery store. I mean, it’s not like they’re Rockefellers or Kennedys or anything.

You can see a lot of such class confusion on display right now in the debate over the expiring Bush tax cuts. President Obama’s position has been that lawmakers should extend tax cuts for 98 percent of Americans and let higher tax rates resume for the wealthiest 2 percent—individuals making more than $200,000 per year or households bringing in more than $250,000. Republicans, in contrast, are standing up for the rich.

Except that they don’t consider those making $250,000 per year to be rich. As James Surowiecki noted in the New Yorker, Fox News has dubbed those at this income level the “so-called rich.” The Right has scored political points by playing on the aspirational hopes (in most cases delusions) of lesser-earning folks who believe that they, too, might someday soon break into the $250,000-per-year stratum.

Recently, Obama has begun to talk of “compromise,” and a number of people on the Left have agreed that a quarter of a million dollars per year is the wrong number at which to draw the class line.

In the vein, Robert Reich argues that singling out those with incomes of $500,000 per year (essentially the top 1 percent of the country) would make for both good economics and good politics. He writes:

“First, the top 1 percent spends a much smaller proportion of their income than everyone else, so there’s very little economic stimulus at these lofty heights.

On the other hand, giving the top 1 percent a two-year extension would cost the Treasury $130 billion over two years, thereby blowing a giant hole in efforts to get the deficit under control.

Alternatively, $130 billion would be enough to rehire every teacher, firefighter, and police officer laid off over the last two years and save the jobs of all of them now on the chopping block. Not only are these people critical to our security and the future of our children but, unlike the top 1 percent, they could be expected to spend all of their earnings and thereby stimulate the economy….

The politics are even clearer. Over the next two years, Obama must clarify for the nation whose side he’s on and whose side his Republican opponents are on. What better issue to begin with than this one?”

Michael Tomasky, writing from the Washington offices of the Guardian, calls for a demarcation at $1 million:

“To cut to the chase, [Democrats] have to give up on this idea that $250,000 is rich in this country. It’s just not. It’s certainly well off. The average two-income household is somewhere around $70,000, last I checked. So 3.5 times that is a lot, no doubt.

But as I’ve written before, a married cop and high-school principal can make a combined 250K after enough years of work. This couple is not a good symbol of excess. Especially if they live in a more expensive urban region—which, in fact, they are likely to, because cops’ and principals’ salaries are higher there.

Lots of liberals get furious at talk like this. But politically, it’s just stupid to lump this couple in with Bill Gates and LeBron James and hedge-fund managers….

The Democrats should aim at millionaires, meaning households with annual incomes above $1 million. That’s clean, it’s easy to grasp. Very few households make a mil, and very few [couples who strive to make $250,000 per year] think they’re going to hit the million mark. Most probably don’t even want to, in the sense that they know it’s basically impossible, so they’ve shut it out, as we do with youthful dreams of being athletes and rock stars.”

Well, you can count me among those made furious by this discussion—or at least among the irked.

I’ll admit that there’s some good political sense in what Reich and Tomasky are saying. If the Dems can make political strides around taxes by focusing on the insanely rich, rather than your standard very-well-to-do rich family, it could be a wise tactical move.

Moreover, since inequality has grown so extreme in the country—with so much income and wealth concentrated at the very tip of the pyramid—there’s economic merit to making the top 1 percent a priority. Certainly, I agree with Surowiecki when he proposes new tax brackets for the astronomically wealthy that would allow us to distinguish between “LeBron James and LeBron James’s dentist.” These new brackets would make those in the former group pay back to society a fairer share than they do now.

At the same time, the conceit that those in the 98th percentile are merely “well off” has produced some stomach-churning sights. One notable example is that of a University of Chicago law professor whose family’s take exceeds a quarter million per year (“but not by that much“) complaining that he is just scraping by. This because, after paying the mortgage on his million dollar home and sending his kids to expensive private schools, he can barely afford to pay for the lawn care and house cleaning services he enjoys, and he’s unable to invest as much as he’d like in the stock market for retirement.

After a while, the question of whether or not we call these people “rich” becomes a farce. I understand that the professor’s family may not be flying around in a private jet, and that they might feel like part of the “middle class.” But as Brad DeLong points out, the household (the total annual income of which turns out to be roughly $450,000) is making nine times more than the average American family. The professor is near the top of the income distribution in a country that is itself one of the wealthiest in the world. He thus enjoys a level of consumption and material well-being unknown to the vast majority of humanity. Yet he shows scant self-awareness of this fact.

I think there is little question that those in the 98th percentile of income can afford to pay in taxes what they were paying back in 2000—hardly a time when the wealthy in America couldn’t get a break. God forbid we ask them to pay what they would have owed back in the time of Nixon.

Do we need a better vocabulary for talking about class in America? Sure. Should we feel sorry, in this time of economic foreclosure and joblessness, for households with two highly paid professionals who are both bringing in reliable salaries? I think not. To accept the idea that those in the top two percent are not very privileged is to buy into the logic that has made the now grotesque levels of inequality in our country possible in the first place.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly called Prince William heir to the British throne. His father, Prince Charles, is in fact the heir.