Is Muhammad Yunus selling ”free market” neoliberalism in the guise of liberal do-gooderism?

Published in the Fall 2009 issue of Dissent magazine.

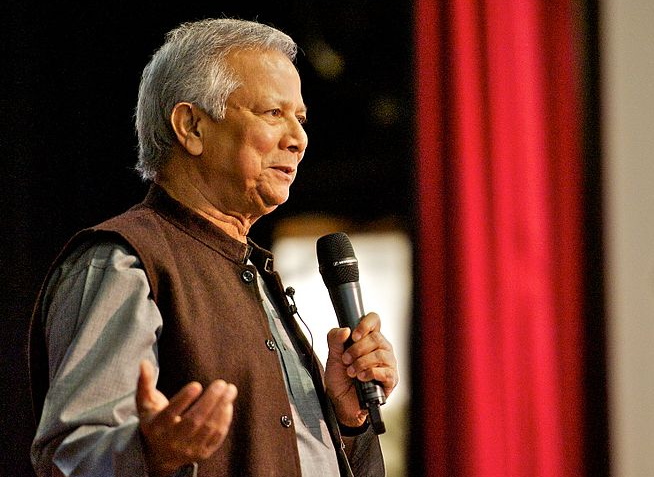

Muhammad Yunus, the Bangladeshi economist, godfather of microcredit, and founder of the now-famous Grameen Bank, enchants many different types of people with his imaginings of a better future. A popular public speaker, Yunus is a relatively short man with a silver mane, a beaming round face, and a perpetually optimistic demeanor. He seems humble even when making grandiose claims, and, with his warm-heartedness, makes whatever he has on offer seem delightfully agreeable. At his talks, he regularly draws standing ovations from socially conscious progressives, business-oriented free-marketers, and numerous personalities in between.

What Yunus has on offer, his supporters would say, is a method for ending poverty. These supporters make up a large group which includes the Norwegian committee that awarded Yunus and his Grameen Bank the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize. This makes things all the more frustrating for Yunus’s detractors. Those to the left would argue that the economist is selling “free market” neoliberalism in the guise of liberal do-gooderism. Right-wing libertarians, in contrast, contend that he is peddling communitarian snake oil in a business-friendly container.

Each position has some merit. And certainly the microcredit movement that he has spawned deserves careful and critical scrutiny. But Yunus himself, as a pitchman and a dreamer, may present something more interesting than either his backers or attackers typically acknowledge—something that may prove unexpectedly relevant in our future. That is, a pre-capitalist vision of a post-capitalist society.

* * * * *

Although the Grameen Bank is not the world’s first micro-lender, it is the most famous, and its story and Yunus’s have entered into the lore of the microcredit movement. Born in 1940, Yunus spent his late twenties studying in the United States on a Fulbright scholarship, earning a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University. In June 1972, shortly after Bangladesh won its independence, he returned to his home country to take a position as a professor of economics at Chittagong University. He dreamed he would be part of building a resilient new nation. Then, in 1974, famine struck. Yunus watched emaciated people use their last strength to travel to the cities in search of help, then slump in the streets, resigned to die.

As a teacher and an economist, Yunus became determined to “abandon classical book learning,” as he writes in his memoir, Banker to the Poor, and instead apply his knowledge to directly addressing the problems of rural poverty. Immersing himself in village life, he became aware of a disturbing financial reality. He met a woman who, working in her mud-floored hut, spent her days making intricate bamboo baskets. They were beautiful, but the woman was never able to profit from her labor. Because she had no savings, she had to turn to a moneylender in order to buy her raw materials each day. By the time she paid him off, she had only pennies to show for her efforts. Yunus surveyed the village and found that forty-two people were similarly trapped in a cycle of quasi-bonded labor even though they had collectively borrowed only $27.

Seeing the amount of misery created by such paltry sums, he offered a loan out of pocket, with the idea that the poor could pay back in small installments. The villagers were thrilled. Inspired, Yunus tried to convince mainstream banks to step in on a larger scale to provide a humane alternative to the loan sharks. When they refused, he devoted himself to creating institutions that could provide small loans to the very poor that would allow them to receive the just profits of their labors. The Grameen Bank was born. Over the next two decades, it became a celebrated success. By 2007, it had distributed six billion dollars in loans in Bangladesh, expanding to serve some seven million people in 78,000 villages.

Yunus’s experiment has been widely replicated, and the basic idea that inspired the Grameen Bank now drives a worldwide microcredit movement. At a 2006 summit, the movement claimed to have reached its goal of providing financial services to one hundred million families to help them “lift themselves… out of poverty.” Yunus posits that the poor have an entrepreneurial drive and well-honed survival skills that they can convert into household businesses if given the opportunity. Lending a poor woman $50 or $100 to buy chickens for a small farm, to purchase yarn for a home weaving operation, or to set up a taco stand outside a nearby factory can allow her to bring in enough income to make the difference between starvation and subsistence and, over time, between destitution and a dignified life.

The Grameen Bank is widely credited for two innovations: lending primarily to women and relying on support groups to ensure a high rate of loan repayment. Early in his microcredit experience, Yunus decided to break a significant cultural taboo and give money to poor women rather than to their husbands. “When men make money, they tend to spend it on themselves,” he writes, “but when women make money, they bring benefits to the whole family, particularly the children.”

Traditional banks deemed these women hopelessly un-creditworthy, as they had no collateral to sacrifice in the event that their loans, however small, went bad. Yunus contended that the poor were trustworthy, and that loans should be given in good faith. To facilitate repayment and heighten a sense of accountability, Grameen gives loans to women in groups of five, so that the groups can meet regularly and provide mutual support. “If an individual is unable or unwilling to pay back her loan, her group may become ineligible for larger loans in subsequent years until the repayment problem is brought under control,” Yunus explains. “This creates a powerful incentive for borrowers to help each other solve problems and—even more important—to prevent problems.” Today, Grameen claims a remarkable repayment rate of 98.6 percent. Other microcredit programs have similarly proven that the world’s poorest often pay back borrowed money reliably.

* * * * *

Considered in ideological terms, the social vision that Yunus sketches constitutes a curious amalgam of left and right. On the one hand, Yunus sounds like a Reaganite. In celebrating bottom-up entrepreneurialism, he rails against “handouts” and denounces the dependency created by welfare systems in Europe and the United States. The pitch for micro-lending fits neatly within the mythos of self-made corporate success. Tellingly, a recent book on the movement, entitled A Billion Bootstraps, trumpets microcredit as “The Business Solution for Ending Poverty.”

On the other hand, Yunus is harshly critical of the global economy’s insensitivity to the plight of the poorest and its erroneous assumption that “all people are motivated purely by the desire to maximize profit.” Some right-wing think tanks, such as the Ludwig von Mises Institute, accuse Yunus of promoting a “far-leftist social agenda” and engaging in “femino-socio-financial engineering.” One of their main objections is that, once borrowers enter into the Grameen system, they are encouraged to participate in a variety of social programs promoting literacy and good health. All borrowers are also made to learn the organization’s “Sixteen Decisions,” among which are, “We shall always be ready to help each other,” “We shall grow vegetables all the year round,” and “We shall take part in all social activities collectively.” According to the Mises Institute, these vows “read like a party platform for collectivist regimentation.”

To sort out Yunus’s ideological jumble, one must appreciate the context in which he developed his hands-on economic philosophy. The Grameen Bank is a product of the Bangladesh of the 1970s and 80s, a country that Henry Kissinger had famously dubbed an “international basket case.” Particularly during periods of desperate famine and catastrophic flooding, no state authority was able to ensure even minimal standards of public wellbeing. Yunus witnessed billions of dollars of foreign aid flow in to the country, only to be siphoned off by wealthy elites who controlled the corrupt government. It is hardly surprising, then, that he suspects state institutions of being more the tools of the privileged than friends to the destitute.

Furthermore, Yunus has focused his efforts on the poorest of the poor. These are individuals who lead lives of precariously minimal subsistence within traditional village economies. Referring to similarly impoverished segments of Brazilian society, liberation theologian Leonardo Boff describes these populations as people who “do not have the privilege of being exploited by capitalism.” They are almost entirely excluded from the modern economy. In this context, Yunus is indeed pro-market. But he is pro-market less in the manner of Milton Friedman than of Karl Marx, who admired capitalism’s tremendous productive capability and its power to break the exploitative bonds of feudal society.

Within their original setting, in places where the poor are left abandoned and jobless, Grameen’s networks of non-state mutual assistance and efforts to make the informal economy marginally more livable seem eminently sensible, though not revolutionary. It is when Yunus’ arguments are transposed into situations with multinational corporations, widespread employment, and functioning welfare states that they become far more conservative—and ripe for appropriation by those less altruistic than he.

* * * * *

A closer examination of microcredit shows that it may not, in the end, be an ideal solution for the precapitalist poor. First, the concept of micro-loans as a vehicle for women’s empowerment appears to have been oversold. Reporting on her field study of Bangladeshi borrowers, Lamia Karim of the University of Oregon wrote in 2008 that, although women were the formal recipients of microcredit, “I found that men used 95 percent of the loans…. In my research area, rural men laughed when they were asked whether the money belonged to their wives. They pointedly remarked that ‘since their wives belong to them, the money rightfully belongs to them.'”

Nor is the money always used for the purposes for which it is loaned. An article in the Harvard Business Review stated in 2007, “Many heads of microfinance programs now privately acknowledge what John Hatch, the founder of FINCA International (one of the largest microfinance institutions), has said publicly: 90 percent of micro-loans are used to finance current consumption rather than to fuel enterprise.” In areas where microcredit has proliferated, some individuals have gotten multiple loans from competing institutions, at times using funds from one program to make overdue payments to another.

In 1989, 60 Minutes profiled a borrower who had once been a beggar. With the help of a series of micro-loans from the Grameen Bank, taken and paid back in good faith, she was able to afford a large plot of land, a herd of seven cows, a new house with proper sanitation, education for her kids, and a small taxi for her husband to use in his own income-generating enterprise. Correspondent Morley Safer described her as “the picture of contentment and human success.”

What did not make it onto the airwaves was that, by 1996, her situation had reversed. Her husband “had contracted a stomach illness that was never properly diagnosed. To pay for his medical treatment, the couple had sold off their taxi, their land, and their cattle. She was so frail and tired, she did not trust herself to take a new loan. All they had left were four chickens.” Critics point to such instances as examples of how inspiring anecdotes of individual success understate the systemic hurdles that keep people trapped in poverty—that microcredit for the poor makes little sense absent health care, job training, and other services.

Microcredit advocates acknowledge that they must constantly reckon with a wide assortment of difficulties. But they deny that this invalidates their work. Yunus is often candid, self-critical, and pragmatic. In fact, it was the economist himself who followed up on the 60 Minutes profile and who decided to include the woman’s full story in Banker to the Poor. He is willing to admit, “microcredit cannot solve society’s every problem.”

Then again, no social program can. For its part, the Grameen Bank has gone far beyond just issuing loans. It has endeavored to couple its microcredit with health insurance, pension accounts, and emergency funds to provide relief in the event of natural disasters. Yunus counters statistic-wielding naysayers with his own evidence, both internal Grameen surveys and independent audits of allied initiatives, that show, at least in specific cases researched, that micro-loans were used for productive investments the bulk of the time and that they resulted in significant improvements in borrowers’ lives.

So what is the overall impact of microcredit? Economists who assess the available data tend to agree that it creates some genuine avenues for advancement by motivated individuals. It fosters a measure of social mobility, which in itself is a good. However, microcredit has not demonstrated an ability to reduce poverty levels on the whole.

Small loans are no substitute for the need to think big. Contrary to the idea that development comes from plucky grassroots entrepreneurs, those countries that have significantly bettered their lot in the past century, from Korea to Chile, have usually relied on aggressive macro-economic policymaking: state-directed development banking, subsidies for strategic industries, and public initiatives consciously designed to create decent jobs. As economist Robert Pollin notes, these policies “have all been closely associated with what used to be termed the ‘developmental state’ economic model,” and have all been substantially dismantled through three decades of market fundamentalism. Developmentalist strategies encountered problems of their own, but neither microcredit nor neoliberalism can claim anything close to their successes in terms of creating growing economies and healthy middle classes.

In the end, macro-decisions can make a huge impact on micro-businesses. When millions of Mexican farmers are driven from their land in the wake of NAFTA, loans for extra chickens appear terribly futile. When a factory is privatized, its union busted, and half of its employees laid off, the micro-borrowers’ lunchtime taco stands no longer seem like such great investments. Viewed modestly, placed among an assortment of tools for helping the poor, micro-loans can be fruitfully pursued along with other initiatives; in this vein, the progressive governments of Venezuela and Bolivia have each explored options for expanding microcredit as part of their policies for fostering small business. But to the extent that microcredit serves an ideological function—reinforcing the belief that an unrestrained market works to the advantage of even society’s least fortunate—it can prove tragically counterproductive.

* * * * *

Today the real problem with micro-lending is probably not the model that Yunus himself developed, but rather the fact that he may have lost control of the animal he did so much to help rear. As microcredit has spread throughout the world, it has spawned a growing faction of practitioners who contend that micro-lending should not be dependent on donations. In order for it to make a really significant impact, they believe, it must be profitable enough to attract private investment. Seeking to tap mainstream capital markets for their work, the bankers in this school prefer to use the term “microfinance” to describe their efforts. The tension between them and the more socially minded, profit-averse “microcredit” institutions now represents a major conflict in the field.

Some predict that the number of microfinance lenders will soon dwarf the number of institutions operating on some version of the Grameen model. The Economist noted in 2005 that, “some of the world’s biggest and wealthiest banks, including Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, HSBC, ING and ABN Amro, are dipping their toes into the water.”

Yunus has long expressed pride in the Grameen Bank’s ability to remain self-sufficient (he claims it has not taken donor money since 1995). And he defends the need for microcredit institutions to charge enough interest so that they can stay in business without continually begging to foundations, governments, and individual donors for new funds. But as the desire of micro-financiers to turn a profit has come into the picture, a heated debate has emerged over the question: What is an acceptable interest rate to charge the poor?

While microcredit is relatively new, usury is very old. A legion of subprime mortgage brokers, credit card companies, payday lenders, and pawnshops have made amply clear that there is nothing inherently beneficent about lending to those of limited means.

The Grameen Bank’s core loans, according to Yunus, are made at a relatively modest interest rate of 20 percent. Those who have looked critically at the issue argue that, after adding taxes, fees, and mandatory savings deductions, and then measuring annual interest rates using the norms of U.S. banking, even Grameen and other socially driven microcredit bodies regularly deal in loans that charge between 30 and 50 percent interest. With for-profit microfinance institutions, the rates can be much higher. In recent years, reporters for Business Week and the New Yorker have pointed to micro-lenders in Mexico who charge interest between 110 and 120 percent.

Compared with the demands of a loan shark exacting 200 or 300 percent interest, these terms might be considered an improvement. But they strain credibility when presented as instruments of poverty relief. Yunus himself is sharply critical of microfinance programs that charge high rates and demand collateral, dubbing their emergence “The Return of the Moneylenders.” Bolivian President Evo Morales has also denounced exploitative interest rates, threatening to put a government cap on the rates charged for micro-loans in his country.

When a borrower accumulates rapidly expanding debt, the threat of reprisal and repossession looms. It turns out that the Grameen Bank’s claim of having a 98.6 percent repayment rate is a bit of an overstatement, and this is probably a good thing. Yunus freely admits that, when borrowers fall on hard times, Grameen is often willing to provide new funds to get them back on their feet, and to generously reschedule old debt obligations. This makes Yunus’s institution a less successful business but a far more compassionate social institution.

However, the micro-loaning world is rife with stories of banking officers using coercive means to keep loans on schedule. Even within Grameen, women in a loaning group who feel compelled to police one other can resort to extreme action. Lamia Karim notes that in her research it was routine to see what Yunus calls “positive social pressure” turn ugly:

“Women would march off together to scold the defaulting woman, shame her or her husband in a public place, and when she could not pay the full amount of the installment, go through her possessions and take away whatever they could sell off to recover the defaulted sum…. This ranged from taking away her gold nose-ring (a symbol of marital status for rural women…) to cows and chicks to trees that had been planted to be sold as timber to collecting rice and grains that the family had accumulated as food, very often leaving the family with no food whatsoever.”

As microfinance continues to develop as a for-profit field, the incentives to treat borrowers leniently appreciably diminish, and the type of community organizing mission embodied in Grameen’s “Sixteen Decisions” takes a back seat to purer business enterprise. The allure of rich returns, many believe, infects the entire endeavor. This, in fact, could be the reason why Yunus has made an assault on profit an increasingly central feature of his later work.

* * * * *

If it is clear that the liberatory power of microcredit is limited at best, Yunus himself remains an engaging figure. In some respects, his new ideas might be bolder than his older ones.

Over the years, as the Grameen Bank expanded, Yunus launched several dozen sister organizations, each designed to provide additional services to the poor. These included an effort to promote traditional handwoven Bangladeshi fabrics; an initiative to develop abandoned fish farms; and, most notably, a plan to provide villages with cell phone service. Grameen Phone, founded in 1996, ultimately grew to become the biggest company in Bangladesh. Out of his experiences with these initiatives, Yunus formed his concept of “social business.”

As described in his book Creating a World Without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism, the idea of social business comes out of a critique of one of the economics profession’s core assumptions in looking at the world: that people are motivated by crass self-interest. Yunus disagrees with this precept. In reality, he writes, “[p]eople are not one-dimensional entities;” instead, they are motivated by a range of beliefs, priorities, and emotions—including the desire to do good for society. Yunus believes that the business world should be reconstructed to reflect this. “[N]ot every business should be bound to serve the single objective of profit maximization.”

In contrast to currently existing businesses, Yunus argues that “[e]ntrepreneurs will set up social businesses not to achieve limited personal gain but to pursue specific social goals”—such as creating sources of renewable energy for remote rural areas, or recycling waste products, or (in an endeavor Grameen is currently pursuing) establishing an eye care clinic that would charge middle-class patients for services but would offer free operations for the poor. The economy, Yunus writes, will be transformed by a “new breed of businesspeople, empowered for the first time to express humanistic values through the companies they found.”

Yunus accepts a role for government and existing non-profit organizations. But he explains that, “when you are running a business, you think differently and work differently than when you are running a charity.” Social businesses make use of private sector know-how and values—except, of course, the paramount value: gleaning a profit for investors. With social business, investors will provide capital out of a desire to improve the world. They might recoup their initial investment over time, but would not make money on the deal.

As a model of what a fully formed social business would look like, Yunus holds up a recent joint venture that he launched when the CEO of Groupe Danone (a major French food corporation and maker of Dannon yogurt) expressed a desire to collaborate. They decided that they would together create a self-sustaining enterprise that would sell low-cost, nutritionally fortified, slightly sweet yogurt that could serve as a nutritious snack for malnourished children in Bangladesh. Their dream came to fruition. In 2007, the first Grameen Danone factory was scheduled to produce 6,600 pounds of yogurt—made in a new eco-friendly facility, using milk from local farmers, and designed to sell for seven cents per container.

The ideology inherent in Yunus’ plan for social business is once again mixed. When discussing his vision, he celebrates corporate culture and the competitive forces of the modern marketplace. Yet, in displacing self-interest as the primary driver of human behavior, he attacks probably the single most cherished tenet of market economics. Yunus is insistent that he wants more “business”—but he wants business that would produce no profit for investors, respect high environmental standards and pay living wages, and produce quality goods at the lowest possible price to benefit the poor. To many, all this will sound decidedly socialistic. To Yunus, social business is the idea that will save capitalism, satisfying a deep human craving for “meaning” that is “totally ignored in the existing business world.”

For the poorest of the poor, the creation of such a new order might mean bypassing the existing business world altogether. In the same way that some countries in the global South have skipped over installing land lines in rural areas and have directly adopted cellular phone technology, Yunus implicitly suggests that those still living on one dollar per day might jump from a world of pre-market subsistence to living in a new, socially minded economy.

Needless to say, there are significant barriers to making a world of social business a reality. Yunus notes that the initial funding for the joint Grameen Danone yogurt project totaled $1.1 million. Meanwhile, in 2005, Groupe Danone had approximately $16 billion in sales. What would happen were the social business to ever grow large enough to truly impact the multinational corporation’s balance sheets? Here, Marx, who described the dynamics by which exploitative businesses are consistently able to pull ahead in acquiring new technology, and thus are empowered over time to drive their kind-hearted competitors into the ground, would seem to have the less rose-tinted perspective on how the business world functions. Indeed, the hijacking of Yunus’ microcredit movement by bankers he likens to the moneylenders of old provides a perfect cautionary tale for those who hope that noble motives can win out in a rapacious global economy.

And yet, being unrealistic does not necessarily render an idea irrelevant. At a time when international social movements struggle to find convincing ways to talk about economic alternatives, Yunus may deserve more than an eye-rolling dismissal. Here is a person who speaks of building a world not based on greed and profit, a world where markets still function but do not control vital aspects of life, and where a different type of socially motivated, cooperatively minded enterprise flourishes. In doing so he brings audiences to their feet, again and again, in the United States as in the rest of the world. It is only fair to ask: Is this not something of which the more calloused and incredulous revolutionary should take note?

__________

Research assistance for this article provided by Sean Nortz. Photo credit: University of Salford Press Office / Wikimedia Commons.