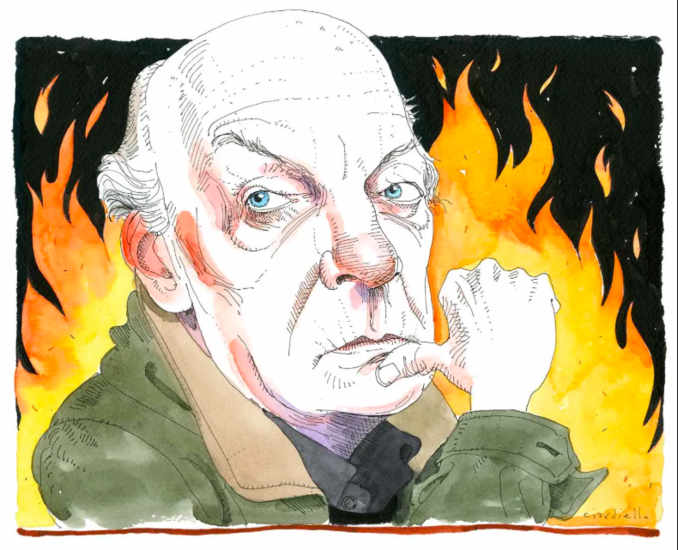

The world of Eduardo Galeano.

Published in the September 10-17, 2018 issue of The Nation.

In at least one case, a book by the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano may have saved a life. In 1997, Víctor Quintana—a Mexican congressman and anti-corruption activist—was abducted by paid assassins, brutally beaten, and threatened with death. By his account, he survived by distracting his assailants with stories about soccer—quirky and lyrical tales drawn from a history of the game that Galeano had recently published. After listening to the adventures of Pelé and Schiaffino, Maradona and Beckenbauer, the killers were moved to depart with Quintana still breathing. “You’re a good guy,” one told him.

In another instance, a book by Galeano proved less propitious. A battered copy of The Open Veins of Latin America, his seminal history of hemispheric exploitation, was found in the knapsack of a guerrilla who was killed fighting El Salvador’s death-squad government. “The book was mortally wounded,” Galeano later recalled. “A bullet hole went from the front cover right through the back.”

The tales of Quintana’s kidnapping and the slain Salvadoran guerrilla are both related by Galeano in Hunter of Stories, a final collection of the author’s work, posthumously released in 2017. Before succumbing to lung cancer in 2015, Galeano was regarded for decades as one of the most prominent literary figures on the Latin American left. He was an important popularizer of economic theory and an innovator of experimental literary vignettes. He helped pioneer the writing of Latin America’s history from below and was a memoirist who juxtaposed his life and times with surrealist collage. Long forced to live in exile, he ended his life welcomed by audiences throughout the world.

Galeano has received considerably less critical attention than other titans of Latin American literature. In part, this has been due to his chosen genre, or lack of one: He preferred the essay and the historical snapshot to the novel. Particularly in his later works, he would blend reportage, anecdote, history, myth, testimony, and travelogue together in one book. But it was also due to Galeano linking his literary ambitions with his radical politics, which some readers—particularly critics in the English-speaking world—felt were too overt and polemical. Yet without his politics, we would have little sense of who Galeano was or why his artistic evolution holds such enduring significance. Galeano’s radical commitments made him an intimate witness to many of the major turns in Latin American politics in the last 75 years. Even as he sought to evoke a common identity for the peoples of a continent that had been battered but remained unbowed, his biography mapped the region’s history.

* * * * *

Eduardo Hughes Galeano was born in 1940 in Montevideo, Uruguay to a family of mixed European origin. The period in which he grew up—from the late 40s to the early 60s—marked the height of what was known as “developmentalist” economics. During this era, various governments, notably that of Juan Perón in Argentina, implemented nationalist experiments in building up local infrastructure, protecting internal markets, and substituting domestic manufacturing for imports. The Southern Cone was developmentalism’s epicenter, with Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile amassing unusually large middle classes, and with the elites in these countries envisioning them as being on a par with rising European states.

Talented and restless, Galeano dropped out of secondary school after just two years and soon became a journalist. By age 14, he was contributing political cartoons to the socialist newspaper El Sol. By 20, he was a managing director of Marcha, a storied weekly in Uruguay. Through the 1960s, he continued to edit while pursuing his own writing. Some of Galeano’s early journalistic dispatches are included in a 1992 collection entitled We Say No. In one, he recounts his time spent with Pelé’s retinue as he awaits an interview with the soccer star—a maneuver that predated Gay Talese’s 1966 New Journalism classic “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” by several years. Scoring other high-profile interviews, Galeano published a skeptical discussion with Perón, a laudatory profile of Che Guevara (an “unheard-of case of a man who abandons a successful revolution he made along with a handful of crazies, to throw himself into launching another”), and a haunting portrait of Pu Yi, the last emperor of China, who had just completed his Maoist reeducation in a nondescript building on the outskirts of Beijing. Galeano also established a friendship with a then-rising Chilean politician named Salvador Allende.

By the 1960s, there were disturbing intimations that the authoritarian national security state was on the rise in Latin America, and that the free press would become one of its first victims. As early as 1954, Guatemala’s mild experiments in nationalist development drew censure when they dared to hint at the prospect of agrarian reform. That year, the country’s democratically elected government of Jacobo Árbenz was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup. Galeano rightly saw this as a defining event in the region’s history, and one of his first books was a combination of reporting, analysis, and personal reflection, later published in English as Guatemala: Occupied Country. Travelling into the densely forested mountains, Galeano spoke with indigenous Mayan villagers and met guerilla leader César Montes, whom he found in a tent reading Pope Paul VI’s encyclical Populorum Progressio.

By the time Galeano’s book appeared in the late 1960s, his own country’s democratic prospects were dimming. In neighboring Brazil, a coup had ousted João Goulart in 1964. As labor strikes escalated in Uruguay after 1967, repression intensified. Under the pretext of fighting off the Tupamaro guerrillas, the state curtailed civil liberties; then, in 1973, a military junta seized control. Allende’s socialist government in Chile fell just a few months later.

Because of his politics and journalism, Galeano soon found himself arrested in Montevideo. “[T]hey put me in a car,” he later wrote. “They moved me and locked me in a cell. I scratched my name on the wall. At night I heard screams.” He could only guess whether he would be detained for days, weeks, or years. In the end, “[i]t was days,” Galeano noted. “I’ve always been lucky.”

Shortly thereafter, he left Uruguay, fleeing first to Argentina, where he helped found and edit the influential magazine Crisis, and then, after the military took over in that country three years later, to Spain. In all, Galeano would spend nearly a dozen years in exile.

* * * * *

It is said that Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks. Galeano claims it took him just over 12 to write The Open Veins of Latin America. Furiously composed as conditions in Uruguay deteriorated, the book was released in 1971. Although Galeano already had several books to his name, Open Veins made his international reputation. It remained, for the rest of his life, his best-known work, eventually appearing in more than 100 official editions and countless bootleg ones.

Author Isabel Allende says that her copy of Open Veins was one of just two books—along with “some clothes, family pictures, [and] a small bag with dirt from my garden”—that she took with her as she fled Chile after Pinochet seized power. For his part, Galeano, who loved ironic reversals, delighted in claiming that the censors were the best promoters of his work. In Hunter of Stories he writes with wry humor that Open Veins “had the good fortune of earning high praise from several military dictatorships, which banned it. The truth is, that’s what gave the book prestige.”

Situating all of Latin America within a common political economy, Open Veins related how, through five centuries of plunder by European conquistadors and American corporations, the region’s abundant natural resources had been extracted to enrich a few local elites and many foreign interests. From the region’s arteries flowed the silver of Potosí and the gold of Ouro Preto, the nitrate of Chile’s pampas, and the sugar of the Caribbean islands.

Galeano emphasized that he approached his subject as a nonspecialist trying to breathe life into the typically wooden histories of the region; “I know I can be accused of sacrilege in writing about political economy in the style of a novel about love or pirates,” he wrote. Yet for all his protestations, Open Veins exhibits a great, erudite density; he not only breathed life, but he got many things right. The editors of Monthly Review Press, which published the U.S. edition, described the book as “perhaps the finest description of the primary accumulation of capital since Marx.”

Open Veins was something else as well—a key work in popularizing what became known as “dependency theory.” Traditional narratives of development held that all countries progress through a series of stages on their road to modernity. As Peruvian liberation theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez explained it, “The underdeveloped countries… were considered backward, having reached a lower level than the developed countries.” Dependency theorists, however, presented a very different thesis: They saw Latin America as a prime example of how countries at the “core” of capitalism fed off raw materials pulled from dependent economies in the “periphery,” thus stunting their capacity for modernization. These theorists argued that the wealth of the North and the poverty of the South went hand in hand. As Galeano put it, with emphasis, “Underdevelopment isn’t a stage of development, but its consequence.”

As important as dependency theory’s tenets was the fact that the theory itself originated in the periphery; it represented a bold set of propositions developed primarily by Latin Americans and rooted in their national experiences. The theory, in other words, represented an intellectual declaration of independence. Not incidentally, dependency theory became the economic framework that undergirded liberation theology, another movement in which Latin American thinkers—Gutiérrez chief among them—asserted an “epistemological break” from European models.

Not all dependency theory was Marxist, but in the hands of its more radical exponents, it suggested changes considerably more explosive than developmentalism’s limited nationalist forays. While Galeano, looking back over the centuries, presented a tale of grim and relentless exploitation, he also saw hope in history’s dialectical motions. He wrote, “The ghosts of all the revolutions that have been strangled or betrayed through Latin America’s tortured history emerge in… new experiments, as if the present had been foreseen and begotten by the contradictions of the past.” When Hugo Chávez gave Barack Obama a copy of Open Veins at a 2009 Summit of the Americas meeting—briefly rocketing the book to the top of Amazon’s sales rankings—it was a gift loaded with significance.

* * * * *

In exile, Galeano enjoyed some of his greatest artistic breakthroughs. During this time, he wrote a moving memoir of the “dirty war” period, Days and Nights of Love and War, as well as an experimental novel. His most important work in the period, however, was an expansive series of historical vignettes, published in three volumes between 1982 and 1986, called Memory of Fire.

Shortly after the publication of Open Veins, Galeano became convinced that political economy afforded him too narrow a focus. “I do not repent,” he wrote; “and yet I am afraid that [Open Veins] may reduce history to a single economic dimension. And if by history I mean reality—a living memory of reality—I mean a… life that sings with multiple voices.” Memory of Fire was Galeano’s attempt to capture these voices and present the Americas in all their sprawling diversity. To orchestrate his vast chorus, he pursued a new literary form, assembling an expansive and impressionistic history of the hemisphere in hundreds of short episodes, many less than a page long.

The narrative starts with pre-Columbian myth, progresses through conquest, colonialism, and independence, and then marches into the present time. On a given page, a reader might find Simón Bolívar or Bessie Smith, Augusto Sandino or Joseph McCarthy, José Clemente Orozco or Buster Keaton. Galeano sketches portraits of indigenous rituals and slave revolts; he shows Isadora Duncan dancing rapturously in Argentina and Pancho Villa learning to read in prison by studying Don Quixote—a tale, the author notes, written by a fellow jailbird.

Galeano saw himself contributing to an effort to rescue the region’s people from an enforced amnesia. At the heart of his pan-American vision was the idea, or perhaps the hope, that there was liberatory potential in the continent’s deepest memories. “Community—the communal mode of production and life—is the oldest of American traditions,” he later wrote in The Book of Embraces. “It belongs to the earliest days and the first people, but it also belongs to the times ahead and anticipates a new New World… Capitalism, on the other hand, is foreign: like smallpox, like the flu, it came from abroad.”

* * * * *

Open Veins and Memory of Fire, both epics in their own way, would have been enough for most careers. But Galeano continued to write for another three decades, devoting himself to the craft of the vignette. The Book of Embraces is arguably the finest example of the style. A synthesis of Galeano’s earlier experiments, the 1989 volume extended the author’s memoirs, recounting his final days of exile. Between autobiographical segments, Galeano interspersed historical sketches, political analysis, prose poems, and anecdotes related to him by others, all rendered in brief snapshots. “When I read your work what I find remarkable is my inability to classify what I am reading,” author Sandra Cisneros wrote in a tribute. Diary, history, testimony, and commentary comingle.

Galeano also employed visual artwork. In The Book of Embraces, he included his own surrealist collages, a cross between Renaissance engravings and the dancing skeletons of José Guadalupe Posada. An image might feature an Aztec warrior emerging from the bell of a tuba or a human eye blossoming at the top of a corn stalk. At one point, Galeano playfully suggested to a friend that they should invent the genre of “Magical Marxism”: “one half reason, one half passion, and a third half mystery.”

Some of Galeano’s later works are organized around specific themes, such as Soccer in Sun and Shadow (1995) and his Mirrors (2008), which extended the project of Memory of Fire into world history. Even more so than most oeuvres, though, his thousands of vignettes can arguably be seen as a single work. Not all these snapshots are equally effective: In his weaker moments, Galeano could be sentimental, predictable, or crudely agitprop, and his texts are best read alongside other histories, not as substitutes for more conventional and measured scholarship. But more often than not, his kaleidoscopic snippets offer fresh twists and stoke the reader’s curiosity about history, both well-known and obscure.

In one vignette from Memory of Fire, Galeano tells of Charles Drew, a pioneer in the creation of blood banks, who resigns from the Red Cross after the organization—wishing to avoid the interracial mixing of blood—banned donations from African Americans during the Second World War. (Drew himself was black.) In another, Galeano rails against the debasement of language, noting that the largest prison under the Uruguayan dictatorship was named “Liberty.” In yet another, he relates the story of an old man who had a chest of love letters stolen from his house, only to have the thieves mail the letters back to him, one by one.

Throughout his later work, Galeano retained a keen sense of political commitment. When he returned to Uruguay in the mid-1980s, he arrived skeptical of the limits that had been imposed on the region’s newly restored democracies. Countries emerging from military rule were saddled with debt and subject to the dictates of the International Monetary Fund, which controlled their access to international credit. Many new governments embraced the role of managing programs of austerity, privatization, and open markets. The era of neoliberal globalization had begun.

In this context, Galeano warned Latin Americans that they were less participants in genuine democracy than spectators of “The Democracy Show.” He likened the lack of choice in determining economic policy to living in medical restraints—anticipating the notorious free-market cheerleader Thomas Friedman, who would perversely try to paint neoliberalism’s “Golden Straightjacket” as a positive. In the 1990s, Galeano’s criticisms positioned him to become an articulate voice in the emergent global justice movement, the broad outlook of which he expressed in his 1998 Upside Down: A Primer for the Looking-Glass World. He attended the first Zapatista encuentro in 1996 and was a high-profile figure at the World Social Forums in Porto Alegre in the early 2000s. While Galeano was a sought-after presence in those years, he never presented himself as an official spokesperson or even as a journalist. Instead, he claimed the role of the storyteller.

* * * * *

In the spring of 2014, rumors circulated that Galeano had come to regret writing Open Veins. The New York Times ran an article on the subject, headlined “Author Changes His Mind on ’70s Manifesto.” Long-time detractors—for whom Galeano was always a one-dimensional polemicist, and dependency theory a simplistic account of relations between North and South—rejoiced. In fact, as he’d done many times in the past, Galeano had simply reiterated at a pubic event that he was neither a trained economist nor an academic historian when he wrote the book, and that—having long since felt compelled to develop a new literary language—he would suffer if forced to reread his youthful prose. As he would later explain, the smug accounts of his alleged repentance were “seriously ill with bad faith.” Any reader of Hunter of Stories, with its celebrations of feminist organizers and outrage over modern-day sweatshops, will quickly learn that Galeano remained unrepentant in his leftist beliefs to the end.

Still, a number of things had significantly changed by the last decade of Galeano’s life. Among radical theorists, dependency has long been a defunct model—not because it was wrong per se, but because it was superseded by world systems analysis, spearheaded by the sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein, which drew on dependency theory’s insights while adding more complexity.

The terrain of practical politics in Latin America had also shifted. In the mid-1960s, when Galeano was making his reputation as a journalist, another young Uruguayan socialist, José Mujica, committed himself to the cause of the Tuparmaro guerillas. Mujica was shot, captured, and imprisoned for more than a decade; then, some 40 years later, he was sworn in as his country’s president. Mujica took office in Uruguay as part of the “pink tide” that brought left-of-center governments to power in Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, and El Salvador as well. Nations that had lived through eras of military dictatorship and market fundamentalism were now being governed by some of these systems’ staunchest opponents.

Latin America’s “pink tide” corresponded to a time in Galeano’s life when he could write freely, travel widely, and lecture to attentive audiences. As the anecdotes in Hunter of Stories relate, he was someone approached in public, and not just for autographs—people wanted to tell him their stories, because it was evident that he knew how to listen. And this marked a stark reversal from a time when he was hunted by death squads instead of admiring fans. When Galeano died in 2015, at the age of 74, a number of the region’s leaders sent condolences to his family. One of them, Bolivian President Evo Morales, mentioned that when he last traveled to Montevideo, he and Mujica had stopped by to see Galeano—just a casual house visit between the writer and two heads of state.

Interestingly, though, as left-leaning governments took office throughout the region, Galeano’s commentary was subdued. He celebrated the 2006 election of Morales—Bolivia’s first indigenous president—and he cheered when Chileans elected Michelle Bachelet, a torture survivor and the country’s first female president. But he remarked little on their subsequent administrations. Ultimately, Galeano was most eloquent and enlivened as a poet of the forgotten and the subjugated—and also of utopian striving and the promise of rebirth. Of the messy politics in between those poles, he had less to say. Therefore, he left key questions unanswered: Was developmentalism doomed to sputter out, or could a new iteration be devised? Could left governments break from fossil fuel “extractivism”? Could social movements and the progressive state remain in constructive tension, or would the relationship inevitably devolve into antagonism?

Such inquiries weren’t a part of Galeano’s literary purview. And so, as they became the dilemmas of the day, the urgency of his writing on the region began to fade. Yet for all of that, there are few engaged writers who could manage to find their way through a rapidly changing landscape as gracefully. Writing in The Nation in 1987 about the first two volumes of Memory of Fire, critic Jean Franco argued that, in the time since Pablo Neruda’s Canto General (1950), the story of Latin American resistance had grown so complicated and diverse that no one literary effort, however ambitious, could hope to contain it. Certainly, there is truth to this—just as it is true that the social and political map suggested by any one life must necessarily be incomplete. But it is also the case that Galeano’s wide-ranging explorations and fragmentary style opened the door to multitudes. “A literature born in the process of crisis and change, and deeply immersed in the risks and events of its time, can indeed help create the symbols of the new reality,” Galeano insisted in a 1976 essay. “It is not futile to sing the pain and beauty of having been born in America.”