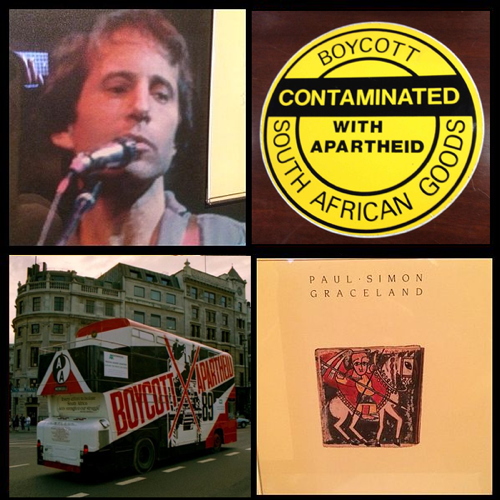

Five stars for entertainment, one for politics.

Published in the April 2014 issue of the New Internationalist.

Back in the 1980s, when this magazine reviewed musical albums, it gave two sets of stars: one for the album’s entertainment value and another for its politics.

Paul Simon’s Graceland received five stars for entertainment, one for politics.

I cherished Graceland as part of the soundtrack of my teenage years. I still love it. But in the wake of Nelson Mandela’s death, I have been reminded of Simon’s early antagonism with the African National Congress.

In January, Steven Van Zandt—well known both as guitarist “Little Steven” in Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band and as gangster Silvio Dante on The Sopranos—gave an interview recounting his efforts to organize artists against apartheid in the 1980s. Paul Simon, who recorded tracks for Graceland in violation of the U.N. cultural boycott of South Africa, didn’t come off well.

When Van Zandt and music critic Dave Marsh encountered Simon at an entertainment industry event shortly after the album’s release, Simon attacked the ANC as a front group funded by Moscow.

“What are you doing defending this guy Mandela?! He’s obviously a communist,” Simon proclaimed, according to the two witnesses. “My friend Henry Kissinger told me about where all of the money [for the ANC] is coming from.”

In producing Graceland, Simon had created a most interesting cultural artifact. Were it not a musical triumph, the decades-old controversy surrounding the album would hardly be worth revisiting. Yet the music still has the power to incite.

First there’s the issue of cultural appropriation. In its review, the NI called Simon’s album “an ingenious fusion of South African and Western music.” The New York-bred pop star shared writing credits, and therefore royalties, with South African musicians on some songs.

But not on others. The “Words and Music by Paul Simon” designation on tracks such as “You Can Call Me Al” fails to acknowledge the innovative hooks provided by guitarist Ray Phiri and bassist Bakithi Kumalo—and it squares poorly with Simon’s recent description of the tune’s grooves coming “straight from the streets of Soweto.”

Musicians including Hugh Masekela, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and Miriam Makeba ultimately defended and performed with Simon, crediting him with bringing their country’s music to a wider audience. But other Africans nodded at trombonist Jonas Gwangwa’s wry rebuttal: “So,” he said, “it has taken another white man to discover my people?”

These debates aside, it was Paul Simon’s stance on the boycott that earned him reproach from the ANC and a one-star political rating from the NI.

In his defense, Simon stresses that he had secured an invitation from South African musicians to record. He also says that he did not understand the nuances of the boycott and contends that, had anti-apartheid groups approached him before Graceland’s release—instead of after the fact—he would have been more receptive.

Yet Simon had brushed aside the counsel of Harry Belafonte, who advised him to seek approval from the ANC before recording. And as his argument with Van Zandt shows, Simon, when pressed, took the route of mouthing Reagan administration talking points rather than siding with those making overt, courageous stands against segregation and prejudice.

The moral: While everyone loves Mandela today, it wasn’t always so. Standing up for social movement dissidents and supporting the boycott of an apartheid state are not always easy or popular stances. To his credit, Simon, like the rest of the world, came to embrace the ANC leader. But his was a belated conversion.

My teenage self was convinced by Paul Simon’s mantra that “art transcends politics.”

Now, were Simon to make the same arguments to me at a party, I can only hope that I would muster something as eloquent as Little Steven’s response: “All due respect, Paulie, but… art is politics,” he said. “And I’m telling you right now, you and Henry Kissinger, your buddy, go f*** yourselves.”

__________

Photo credits: Sam Howzit / CC BY; R Barraez D´Lucca / CC BY; Djembayz / CC BY-SA (Wikimedia Commons).