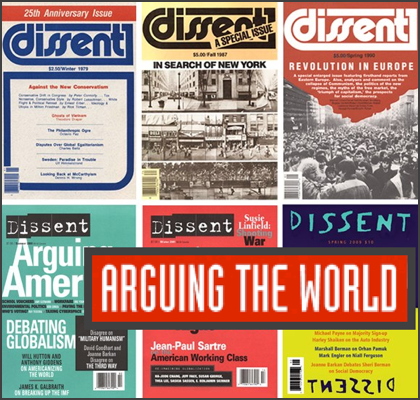

A dispatch for the “Arguing the World” blog at Dissent magazine.

Published in Dissent.

Full disclosure: I find New York Times columnist David Brooks exceedingly annoying, and I have no intention of reading his most recent book, The Social Animal.

Having said that, I’m having a good week, and Brooks a very bad one. Either that, or he’s remaining willfully ignorant of the acutely barbed criticism of his work that has been popping up at a steady clip in recent days.

It started when the Nation published a classic smackdown of The Social Animal by Gary Greenberg, a psychotherapist and the author of Manufacturing Depression: The Secret History of a Modern Disease. Fellow Dissent blogger Lindsay Beyerstein has commented that Greenberg’s review is the most satisfying evisceration of a blowhard pundit “since Matt Taibbi savaged Tom Friedman’s The World is Flat.” (I’m not inclined to argue the point, although I’m sure I’d have fun reading other entries into that category.)

Greenberg takes Brooks to task for dabbling in neuroscience and cognitive psychology and then using his “findings” in these fields to ill effect: first, to give faux respectability to the conservative columnist’s favored vision of human nature; and, second, to provide an explanation for why liberal “attempts to narrow income inequality, stabilize the economy, spread democracy, and reduce political polarization have failed.” (Namely, Greenberg summarizes, because they allegedly “don’t mesh with our neuropsychological infrastructure.“)

Greenberg writes in response:

“It is easy to wish, upon reading The Social Animal, that Brooks had stayed in his basement with his collection of books and scientific journals, occasionally sprinkling anecdotes about the latest amazing neuroscientific finding into his columns and lectures and Beltway chitchat. Not for our sake—after all, the book is no less genial, and no more infuriating, than his day-job commentary—but for his. The Social Animal is a deep and public embarrassment, a lumpy hybrid of fiction and science that fails at both, and so miserably that at least for a moment you feel bad for the guy. Because it is clear that he means every word, that this loose baggy monster, the bastard offspring of Malcolm Gladwell and Kilgore Trout, is a true love child.”

Greenberg is just getting started here, and—unfortunately for Brooks—the Nation editors gave him plenty of space to work through the main arguments and assumptions of the book. The review is well worth enjoying in full.

As I previously indicated, I haven’t read The Social Animal myself, and I have no plans to. But I’ve delved deeply enough into the literature of bullshit sociobiology to smell the crap coming from some distance. Even from a safe remove, The Social Animal reeks.

I will not excuse progressives from the fault of drawing ridiculously over-generalized conclusions from evolutionary theory and contemporary neuroscience. I recently reviewed Tim Flannery’s new book, Here On Earth: A Natural History of the Planet, in which the author makes a variety of sociobiological claims about how we might be “hard-wired” to live in sync with Mother Nature. I Am, the liberal, feel-good documentary about social engagement and the meaning of life, is another example. That film tried hard to establish that evolution has predisposed human beings toward the cooperative, democratic sharing of group hugs in public places.

I didn’t buy the argument in those venues either, but at least I didn’t have to stomach contrived parables about how post-Reagan consumer capitalism is the best of all possible worlds.

While the Greenberg review might be the sharpest blow landed against Brooks this week, it has not been the only one. Just in time for President Obama’s trip abroad, Brooks wrote a column from England celebrating the British political system. He argued that, just as the British moved “gradually” from “an aristocratic political economy to a democratic, industrial one” in the opening decades of the 1900s, the country has now entered into a peaceful end-of-history phase. Since Thatcher “liberat[ed] the economy” in the 1980s, the country’s political parties can now agree to each “come up with new ways to measure government performance, reduce welfare dependency, and improve early childhood programs.”

Alternet’s Joshua Holland pointed to a very effective response by Daniel Knowles in the Telegraph entitled, “David Brooks of the New York Times thinks he understands Great Britain. He doesn’t.” Knowles wrote:

‘No doubt Mr. Brooks’ Westminster admirers will lap this up—is there anything we love more than being told how good we are by foreigners? But this column is laughably ignorant of British history and bizarrely naive about British political culture.

Let’s take a few choice bits, starting with the opening paragraph. Apparently, from 1900 to 1920:

“Britain faced an enormous task: To move from an aristocratic political economy to a democratic, industrial one. This transition was made gradually, without convulsion, with both parties playing a role.”

Gradually? Without convulsion? I don’t know if you’re aware of this David, but most British historians believe that the First World War was pretty convulsive. And definitely not very gradual. He seems to think that Britain cast off her aristocratic rulers by a process of “constructive competition.” In fact, what happened was that we went to war, conscripted millions of young men and sent them to France to be machine-gunned. Simultaneously, our government was taken over by a clique, led by Lloyd George, which ruled autocratically from a garden shed in No. 10 Downing Street. Meanwhile, a whole part of the country—Ireland—descended into civil war. Somehow, I don’t see that as a “gradual” transformation.’

The well-earned abuse continues from there.

Of course, it should be said that picking a fight with David Brooks is not exactly the most daring move a political commentator can make. On this note, I will close with the observation of a friend. He wrote to me, “Mocking David Brooks is somehow both the lowest of low-hanging fruit and vital to our democracy. It’s a puzzle.”