Did the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization actually make a difference? Yes. Here’s how.

Published in Yes! Magazine.

Ten years ago this fall, Kevin Danaher, the bareheaded, white-goateed co-director of Global Exchange was making the rounds to student groups, encouraging young people to join in upcoming protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO). He had worked up a theatrical pitch:

“How many people here were at Woodstock?” he would ask, and, with his own hand raised, look over his audiences.

“Only me, eh? Well that’s too bad for you. But if you want to be part of something equally important and historic, you get your ass to Seattle.”

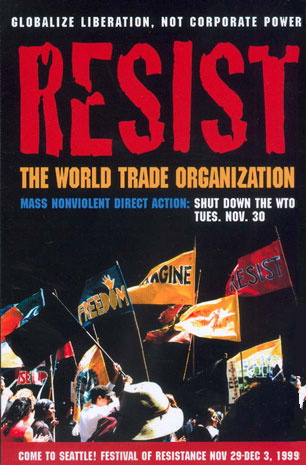

Before the fact, and amid an era of celebration for corporate globalization, this prediction of the actions’ magnitude seemed exaggerated at best. Afterwards, not so much. The protests—a massive grassroots effort by unions, environmentalists, organic farmers, solidarity activists, and diverse community groups—made headlines around the world. They marked the beginning of a new phase of popular mobilization around issues of corporate power and international trade. They even inspired a 2008 film dramatization, Battle In Seattle, which featured Hollywood stars Woody Harrelson, Michele Rodriguez, Charlize Theron, and Andre 3000.

But, in the long run, did the protests promote meaningful change?

In assessing any single historical incident, this question is a difficult one. Generally speaking, the response of many Americans is to dismiss protests out of hand—arguing that demonstrators are just blowing off steam and won’t make a difference. But if any case can be held as a counter-example, Seattle is it.

The 1999 mobilization against the World Trade Organization has never been free from criticism. As Andre 3000’s character in the movie quips, even the label “Battle in Seattle” makes the protests sound less like a serious political event and more “like a Monster Truck show.” While the demonstrations were still playing out and police were busy arresting some 600 people, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman issued his now-famous edict stating that deluded activists were just “flat-earth advocates… looking for their 1960s fix.” (Comparisons to Woodstock might not have helped with the latter charge.) In 2008, an article in the dismissively asked, “Remind me again what those demonstrations against the WTO actually accomplished?”

While cynicism comes cheap, those concerned about global poverty, sweatshop labor, outsourced jobs, and threats to the environment can witness remarkable changes on the international scene. Today, trade talks at the WTO are in shambles, sister institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund have been knocked from their once-imposing pedestals, and the ideology of neoliberal corporate globalization is under intense fire, with mainstream economists defecting from its ranks and entire regions such as Latin America in outright revolt. As global justice advocates have long argued, the forces that created these changes “did not start in Seattle.” Yet few trade observers would deny that the week of protest late in the last millennium marked a critical turning point.

* * * * *

What Happened in Seattle?

During and after the demonstrations, the mainstream media was largely focused on the smashed windows of Starbucks and Niketown—property destruction carried out by a small minority of protesters. In the past two decades, the editorial boards of major U.S. newspapers have been more dogged than even many pro-corporate legislators in pushing the “free trade” agenda. Yet, remarkably, acknowledgement of the WTO protests’ impact on globalization politics could be found even in their pages. Shortly after the event, a front-page story in the Los Angeles Times read, “On the tear-gas shrouded streets of Seattle, the unruly forces of democracy collided with the elite world of trade policy. And when the meeting ended in failure… the elitists had lost and [the] debate was changed forever.”

Seattle was supposed to be a moment of crowning achievement for corporate globalization. Big-business sponsors of the Seattle Ministerial (donors of $75,000 or more included Procter & Gamble, Microsoft, Weyerhaeuser, Boeing and GM) invested millions to make it a showcase of “New Economy” grandeur. Any student of public relations could see that the debacle they experienced instead could hardly be less desirable for advancing their agenda.

Rarely do protesters have the satisfaction of achieving their immediate goals, especially when their stated aims are as grandiose as shutting down a major trade meeting. Yet the direct action in Seattle did just that on its first day, with activists chained around the conference center forcing the WTO to cancel its opening ceremonies.

By the end of the week, negotiations had collapsed altogether. Trade representatives from the global South, emboldened by the push from civil society, launched their own revolt from within the conference. In a statement from the Organization of African Unity ministers railed against “being marginalized and generally excluded on issues of vital importance for our peoples and their future.”

The demands of the developing countries’ governments were not always the same as those of the outside protesters. However, the diverse forces agreed on some key points. Expressing his disgust for how the WTO negotiations had been conducted, Sir Shridath Ramphal, the chief Caribbean negotiator, argued, “This should not be a game about enhancing corporate profits. This should not be a time when big countries, strong countries, the world’s wealthiest countries, are setting about a process designed to enrich themselves.”

Given that less powerful countries had typically been bullied into compliance at trade ministerials, this was highly unusual stuff. Yet it would become increasingly normal. Seattle launched a series of setbacks for the WTO and, to this day, the institution has yet to recover. Efforts to expand the reach of the WTO have repeatedly failed. The overtly unilateralist Bush White House was even less effective than the “cooperative” Clinton administration at getting its way in negotiations, and the Obama administration has yet to change things.

In 2008 analyst Walden Bello dubbed the current round of WTO talks the “Dracula Round” because it lives in an undead state. No matter how many times elites try to revive the round, it seems destined to suffer a new death. Other agreements, such as the Free Trade Area of the Americas, which aimed to extend NAFTA throughout the hemisphere, and which drew protests in places like Quebec City and Miami, have since been abandoned altogether.

* * * * *

“We Care Too”

The altered fate of the WTO and other “free trade” deals is itself very significant. But this is only part of a wider series of transformations that the global justice protests of the Seattle era helped to usher in. The Seattle protests launched thousands of conversations about what type of global society we want to live in. While they have often been depicted as mindless rioters, activists were able to push their message through. A poll published in Business Week in late December 1999 showed that 52 percent of respondents were sympathetic with the protesters, compared with 39 percent who were not. Seventy-two percent agreed that the United States should “strengthen labor, environmental, and endangered species protection standards” in international treaties, while only 21 percent disagreed.

A wave of increased sympathy and awareness dramatically changed the climate for long-time campaigners. People who had been quietly laboring in obscurity for years suddenly found themselves amid a huge surge of popular energy, resources, and legitimacy. Obviously, the majority of Americans did not drop everything to become trade experts. But an impressive number, especially on college campuses and in union halls, did take time to learn more—about sweatshops and corporate power, about global access to water and the need for local food systems, about the connection between job loss at home and exploitation abroad.

With the protests that took place in the wake of Seattle, finance ministers who had grown accustomed to meeting in secretive sessions behind closed doors were suddenly forced to defend their positions before the public. Often, official spokespeople hardly offered a defense of WTO, IMF, and World Bank policies at all. Instead they spent most of their time trying to convince audiences that they, too, cared about poverty. In particular, the elites who gather annually in the Swiss Alps for the exclusive World Economic Forum became obsessed with branding themselves as defenders of the world’s poor. The Washington Post noted of the 2002 Forum, “The titles of workshops read like headlines from the Nation: ‘Understanding Global Anger,’ ‘Bridging the Digital Divide,’ and ‘The Politics of Apology.'”

Joseph Stiglitz, a former chief economist of the World Bank who was purged after he outspokenly criticized the IMF, perhaps most clearly described the remarkable shift in elite discussion that has taken place since global justice protests first captured the media spotlight. In a 2006 book, he wrote:

“I have been going to the annual meetings [in Davos, Switzerland] for many years, and had always heard globalization spoken of with great enthusiasm. What was fascinating… was the speed at which views had shifted [by 2004]… This change is emblematic of the massive change in thinking about globalization that has taken place in the last five years all around the world. In the 1990s, the discussion at Davos had been about the virtues of opening international markets. By the early years of the millennium, it centered on poverty reduction, human rights, and the need for fairer trade arrangements.”

* * * * *

Changing Policy

Of course, much of the shift at Davos was just talk. But the wider political changes go far beyond rhetoric. Specific elements of the neoliberal “Washington Consensus,” such as prying open countries’ capital markets, fell into disrepute amid widespread criticism. As Stiglitz noted in 2006, “Even the IMF now agrees that capital market liberalization has contributed neither to growth nor to stability.” That was well before the start of the current economic crisis, which has gone much further in discrediting market fundamentalist policies.

Grassroots activity translated into concrete change on other levels as well. Even some critics of the global justice movement have noted that activists have scored a number of significant policy victories. In a September 2000 editorial entitled “Angry and Effective,” The Economist reported that the movement

“has changed things — and not just the cocktail schedule for the upcoming meetings. Protests… succeeded in scuttling the OECD’s planned Multilateral Agreement on Investment in 1998; then came the greater victory in Seattle, where the hoped-for launch of global trade talks was aborted… The activists have also raised the profile of “backlash” issues — notably, labor and environmental conditions in trade, and debt relief for the poorest countries. This has dramatically increased the influence of mainstream NGOs, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature and Oxfam. Such groups have traditionally had some say (albeit less than they would have wished) in policymaking. Assaulted by unruly protesters, firms and governments are suddenly eager to do business with the respectable face of dissent.”

Various combinations of “respectable” negotiators and “unruly” dissidents forced shifts on a wide range of issues. It is not glamorous work to trace the issue-by-issue changes that activists have eked out—whether it’s compelling multinational pharmaceutical companies to drop intellectual property lawsuits against African governments seeking to provide affordable AIDS drugs for their citizens, or creating a congressional ban on World Bank loans that impose user fees on basic health care and education for the poor, or persuading administrators at more than 140 colleges to make their institutions take part in the anti-sweatshop Worker’s Rights Consortium. Yet these changes affect many lives.

Take just one demand: debt relief. For decades, countries whose people suffer tremendous deprivation have been forced to send billions of dollars to Washington in payment for past debts—many of which were accumulated by dictators overthrown years ago. Debt relief advocates were among the thousands who joined the Seattle mobilization, and they saw their cause quickly gain mainstream respectability in the altered climate that followed. In 2005, the world’s wealthiest countries agreed to a breakthrough debt cancellation agreement that, while imperfect, shifted roughly $1 billion per year in resources back to the global South.

In early 2007, Imani Countess, national coordinator of the American Friends Service Committee Africa Program, noted that the impact of the deal has been profound:

“In Ghana, the money saved is being used for basic infrastructure, including rural feeder roads, as well as increased expenditure on education and health care.

“In Burundi, elimination of school fees in 2005 allowed an additional 300,000 children to enroll.

“In Zambia, since March 31, 2006, free basic health care has been provided for all [along with] a pledge to recruit 800 medical personnel and slightly over 4,000 teachers.

“In Cameroon, [the government made] a pledge to recruit some 30,000 new teachers by the year 2015 and to construct some 1,000 health facilities within the next six years.”

“They won the verbal and policy battle,” said Gary Hufbauer, a “pro-globalization” economist at the Institute for International Economics in 2002, speaking of the groups that have organized major globalization protests. “They did shift policy. Are they happy that they shifted it enough? No, they’re not ever going to be totally happy, because they’re always pushing.”

* * * * *

A Crisis of Legitimacy

In its review of Battle in Seattle, the Hollywood industry publication Variety noted that “the post-9/11 war on terror did a great deal to bury [the] momentum” of the global justice movement. This idea has become a well-worn trope; however, it is only partially true. In the wake of 9/11, activists did shift attention to opposing the Bush administration’s invasion and occupation of Iraq. But, especially in the global South, protesters combined a condemnation of U.S. militarism with a critique of “Washington Consensus” economic policies. In the post-Seattle era, these polices faced a crisis of legitimacy throughout much of the world.

Privatization, deregulation, and corporate market access have failed to reduce inequality or create sustained growth in developing countries. This led an increasing number of mainstream economists, Stiglitz most prominent among them, to question some of the most cherished tenets of neoliberal “free trade” economics. Not only are the intellectual foundations of neoliberal doctrine under assault, the supposed beneficiaries of these economic prescriptions have been walking away. Throughout Latin America, waves of popular opposition to Washington Consensus policies have forced conservative governments from power. In election after election since the turn of the millennium, the people have put left-of-center leaders in office.

More recently, similar disaffection has reached the United States. Last year, as the current economic crisis was escalating, we were afforded the rare sight of Sen. John McCain blasting “Wall Street greed” and accusing financiers of “[treating] the American economy like a casino.” Meanwhile, then-candidate Obama decried the removal of government oversight on markets and the doctrine of trickle-down prosperity as “an economic philosophy that has completely failed.” In each case, their words might have been plucked from Seattle’s teach-ins and protest signs.

With Obama now in the White House, there is an on-going need to compel him and others in power to transform campaign-trail rhetoric into a real rejection of corporate globalization. The White House has been ambivalent about whether it will promote new “free trade” agreements. And the WTO, while bruised and battered, has not been eliminated entirely. Because its original mandate is still intact, the institution has considerable power in dictating the terms of economic development in parts of the world. Opposing this will require continued grassroots pressure.

On a broader level, huge challenges of global poverty, inequality, militarism, and environmental degradation remain. Few, if any, participants in the 1999 mobilization believed that a single demonstration would eliminate these problems in one tidy swoop. But the coming fight will be easier if the spirit that drove the Seattle protests animates a new surge of citizen activism in the Obama era.