Alex Rivera, director of the new film Sleep Dealer, imagines the future of the Global South.

Published in Foreign Policy In Focus.

Tapping into a long tradition of politicized science fiction, the young, New-York-based filmmaker Alex Rivera has brought to theaters a movie that reflects in news ways on the disquieting realities of the global economy. Sleep Dealer, his first feature film, has opened in New York and Los Angeles, and will show in 25 cities throughout the country this spring.

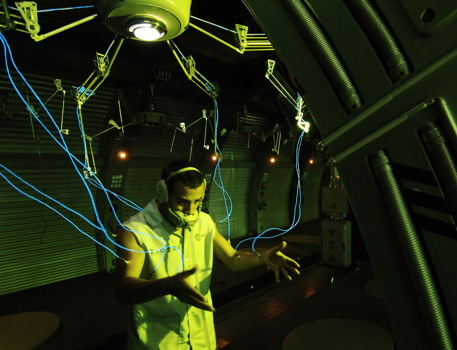

Set largely on the U.S.-Mexico border, Sleep Dealer depicts a world in which borders are closed but high-tech factories allow migrant workers to plug their bodies into the network to provide virtual labor to the North. The drama that unfolds in this dystopian setting delves deeps into issues of immigration, labor, water rights, and the nature of sustainable development.

Rivera’s film drew attention by winning two awards at Sundance—the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award and the Alfred P. Sloan Prize for the best film focusing on science and technology. Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan wrote of the movie, “Adventurous, ambitious and ingeniously futuristic, Sleep Dealer… combines visually arresting science fiction done on a budget with a strong sense of social commentary in a way that few films attempt, let alone achieve.”

Rivera spoke with Foreign Policy In Focus senior analyst Mark Engler by phone from Los Angeles, where the director was attending the local premier of his movie.

M.E.: How do you describe your film?

A.R.: Sleep Dealer is a science fiction thriller that takes a look at the future from a perspective that we’ve never seen before in science fiction. We’ve seen the future of Los Angeles, in Blade Runner. We’ve seen the future of Washington, D.C., in Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report. We’ve seen London and Chicago. But we’ve never seen the places where the great majority of humanity actually lives. Those are in the global South. We’ve never seen Mexico; we’ve never seen Brazil; we’ve never seen India. We’ve never seen that future on film before.

M.E.: Your main character, Memo Cruz, is from rural Mexico, from Oaxaca. In many ways, the village that we see on film is very similar to many poor, remote communities today. It doesn’t necessarily look like how we think about the future at all. What was your conception of how economic globalization would affect communities like these?

A.R.: One of the things that fascinates me about the genre is that, explicitly or not, science fiction is always partly about development theory. So when Spielberg shows us Washington, DC with 15-lane traffic flowing all around the city, he’s putting forward a certain vision of development.

Sleep Dealer starts in Oaxaca, and to think about the future of Oaxaca, you have to think about how so-called “development” has been happening there and where might it go. And it’s not superhighways and skyscrapers. That would be ridiculous. So, in the vision I put forward, most of the landscape remains the same. The buildings look older. Most of the streets still aren’t paved. And yet there are these tendrils of technology that have infiltrated the environment. So instead of an old-fashioned TV, there is a high-definition TV. Instead of a calling booth like they have today in Mexican villages, where people call their relatives who are far away, in this future there is a video-calling booth. There’s the presence of a North American corporation that has privatized the water and that uses technology to control the water supply. There are remote cameras with guns mounted on them and drones that do surveillance over the area.

The vision of Oaxaca in the future and of the South in the future is a kind of collage, where there are still elements that look ancient, there is still infrastructure that looks older even than it does today, and yet there are little capillaries of high technology that pulse through the environment.

ME: How far into the future did you set the film?

A.R.: I started working on the ideas in Sleep Dealer ten years ago, and at that point I thought I was writing about a future that was forty or fifty years away, or maybe a future that might not ever happen. Over this past decade, though, the world has rapidly caught up with a lot of the fantasy nightmares in the film. That’s been an interesting process.

But, you know, a lot of times we use the word “futuristic” to describe things that are kind of explosions of capital, like skyscrapers or futuristic cities. We do not think of a cornfield as futuristic, even though that has as much to do with the future as does the shimmering skyscraper.

M.E.: In what sense?

A.R.: In the sense that we all need to eat. In the sense that the ancient cornfields in Oaxaca are the places that replenish the genetic supply of corn that feeds the world. Those fields are the future of the food supply.

For every futuristic skyscraper, there’s a mine someplace where the ore used to build that structure was taken out of the ground. That mine is just as futuristic as the skyscraper. So, I think Sleep Dealer puts forward this vision of the future that connects the dots, a vision that says that the wealth of the North comes from somewhere. It tries to look at development and futurism from this split point of view—to look at the fact that these fantasies of what the future will be in the North must always be creating a second, nightmare reality somewhere in the South. That these things are tied together.

M.E.: It’s interesting that at the recent Summit of the Americas, Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez gave President Obama a copy of Eduardo Galeano’s Open Veins of Latin America. This is a book that was written over 30 years ago, but that really emphasizes the same point that you are making now, that underdevelopment is not an earlier stage of development, but rather is the product of development. That development and underdevelopment go hand in hand.

A.R.: Exactly. And I think that you can also add immigration into that mix. Because the history that Open Veins lays out is a lot about resource exploitation and transfer from South to North. And today, of course, one of the main entities that places like Mexico export is workers.

M.E.: There’s a quote from the film that says a lot. Memo’s boss, who runs this sort of high-tech Mexican sweatshop, says, “We give the United States what it’s always wanted. All the work without the workers.” Can you describe this concept of the “cybracero” that you have been developing?

A.R.: The central idea for this film occurred to me about ten years ago when I was reading an article in Wired magazine about telecommuting. The article was making all of these fantastic predictions that, in the future, there won’t be any traffic jams anymore, and no one will have to ride the subway, because everyone will work from home. Well, I come from a family that’s mostly immigrant, a family in which my cousins are still arriving and working in landscaping and construction. I tried to put them into this fantasy of working from home—when their home is Peru, 3000 miles away, and their work is construction.

And so I came up with this idea of the telecommuting immigrant, where in the future the borders are sealed, workers stay in the South, and they connect themselves to a network through which they control machines that perform their labor in the North.

The end result is an American economy that receives the labor of these workers but doesn’t ever have to care for them, and doesn’t have to fear that their children will be born here, and doesn’t ever have to let them vote.

When I started this project, the idea of a remote worker was political satire. About eight years ago, it became a reality in the call centers of India and in the idea of off-shoring information-processing jobs that could be done in real time by people on the other side of the planet.

My movie goes further by putting forward a vision of remote manual laborers. What if somebody in India could drive a taxi in New York or bus dishes in a restaurant in Los Angeles? I wonder, do we live in a world where it would be acceptable to have someone in Jakarta laying the bricks for a building that’s being built next door to us?

I think under the rules of the economy that we live with, if that were technically possible, it would be considered morally acceptable. It’s just another stage of globalization. Yet it seems so surreal, and it makes me wonder: What kind of social order would that produce? What kind of communities would that produce?

M.E.: At the same time, I think in the film you suggest that this new technology also has the possibility to connect people across great distances. I wonder how you weigh the alienating effects of technology with some of its redemptive potential?

A.R.: To me, Sleep Dealer is a parable, a myth. There are three characters: One is a remote worker. The second is a remote soldier—a person who is in the United States but flies a drone that patrols the South. And the third character is a kind of writer, a blogger, who connects her body to the network and uploads, not words that she is typing, but rather her memories. And by sharing her memories she is able to let people see these far-away realities that maybe they’re not supposed to. She’s able to use technology to erase borders for a moment.

And to me, that is the tension of the moment we’re living in. We live in a moment when the military is using technology to wage remote war. Corporations are using technology to move extraordinarily quickly around the globe to take advantage of weak environmental standards and weak labor standards.

And yet, we’re living in the moment of the social forums, which are organized over the network. We’re living in the age of the Zapatistas, who in 1994 sent messages by horseback, messages written on paper, to Internet cafes where they could be sent out as press releases and could be used to build a global network of solidarity. We’re living in a time when I’m starting to hear tremors from the labor movement about creating cross-border unions, which will also be built over the network.

So I think we’re in this moment when we don’t know who will be more empowered by this connectivity and by new technology. And that’s the battle in Sleep Dealer. It’s over the future of this connected planet and what kind of globalization we’ll be living in.

M.E.: Beyond immigration politics, the commodification and privatization of water is a major theme in the film. How did you choose water as an issue you would focus on?

A.R.: When I look at dramas of immigration, one of the things that I find unsatisfying is that they always focus on an internal dream, a dream that someone has of going to America and making his or her life better. And, instead, what I wanted Sleep Dealer to start with was this idea that immigrants from Latin America, in the places where they’re born, are usually living somehow in the shadow of U.S. intervention, that immigrants come here because we—the United States—are already there.

In my film I wanted to have a presence of U.S. power in my character’s village. And so I put in a dam. The dam controls the local water supply, and it makes traditional subsistence life much more difficult. In reality, in Latin America, it’s been banana plantations controlled by paramilitaries. It’s been gold mines and copper mines and silver mines. It’s been oil fields. It’s any number of situations that have made it hard for the people there to survive.

I chose water because it also has a symbolic and spiritual dimension to it. When my characters have their first kiss, they are by a little river. When they make love, they go down by the ocean. It would have been a lot harder to do that with petroleum.

M.E.: But, of course, struggles over the control of water are not purely metaphorical.

A.R.: When you talk to people about this, the idea that an evil corporation would go in and take the water from the people sounds so bombastic, so bizarre, that it feels like science fiction. And yet it’s absolutely happening today.

A lot of people are familiar with the story of Cochabamba, Bolivia, where an American company, Bechtel, privatized the water, and there literally was a water war. All of this stuff can sound like a bad Kevin Costner movie—the idea of a water war—and yet it’s one of those realities that, if you were to graph it, is only going to trend upwards in terms of its intensity in the future.

M.E.: The characters in the film are moved to take action about water privatization. Yet this takes the form of a highly individualized type of action—they don’t join a social movement. I wondered about the absence of more collective resistance in the movie.

A.R.: Well, I think you’ve hit on the Achilles’ heel of political narrative film. Narrative film is driven by psychology and by identifying with a character. And I think that’s why there are so few truly transcendent political films. In narrative cinema we’re used to identifying with one person, and so even if the story is anti-imperial or anti-racist or anti-misogynist, it’s usually one character’s journey in overcoming those things.

In Sleep Dealer there are three characters that represent three vast segments of our society. Those characters are in conflict at first, and then they come together. And their story is meant to have larger resonance than just the three individuals.

But I think that devising a narrative where political hope and political power doesn’t belong to one actor, but is somehow made collective, that is very, very challenging. I look at The Battle of Algiers as an incredible model, where there is a single character—Ali la Pointe—who we meet, but then his subjectivity sort of bleeds away from him and is given to a social movement by the end of the film.

That film is a masterpiece; I am but a learner. When we were writing Sleep Dealer we were trying to think about what the future of what a radically networked social movement would look like, but we couldn’t get there. Instead, I think the contribution of Sleep Dealer is in being a parable, a myth, that thinks through some of the impulses of globalization.

M.E.: How did you first come to this type of work?

A.R.: I grew up in upstate New York, and when I was 15 years old I met Pete Seeger. Without knowing who he was, I ended up doing volunteer work for one of his organizations. After meeting him I learned about his life using music and song as a part of social movements. When I went to college, that’s what I went to study—music and social movements.

M.E.: So you had taken up the claw-hammer banjo?

A.R.: I did learn how to play the five-string banjo, actually! I can still do it. But at a certain moment I decided that the banjo wasn’t the future of social movements. And I decided that through film and video you could express much more complicated and subtle arguments about the world than you can through song.

M.E.: I think you’re pissing off all of the political songwriters out there.

A.R.: With song I think you have an access to the spirit, access to the heart. But with film we have two hours with people trapped in a dark room. You can refer back to something that happened 60 minutes earlier in the film, and you can play with what your viewers remember, and you can build really intimate relationships with characters. You can lay out both an emotional journey and an intellectual argument. I don’t think there’s anybody who will say that you can do all of that in a song.

M.E.: Are you concerned with being pigeonholed as a political filmmaker or having the movie labeled as a “political” film?

A.R.: I’d be happy to be pigeonholed as a political filmmaker. For me, making a film is so difficult and so challenging that I only want to make films that are relevant to the world we live in.

M.E.: Do you see a trend toward politics, or maybe away from politics, in science fiction filmmaking today?

A.R.: Science fiction has always had a radical history, all the way from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, which is a comedic portrait of fascism, up to Gattaca, which looks at the way that DNA profiling could be used by the government, to Children of Men, to Michael Winterbottom’s Code 46.

Science fiction has always been a space for radical critique on one hand, and, on the other, for selling Happy Meals. I do think that science fiction today is at risk of being completely co-opted by superhero movies, big franchises, and xenophobic fantasies about space aliens. It has that face as well. But I think the long history, going back almost a hundred years, is of science fiction as a place for forward-thinking, radical thought.

M.E.: Perhaps unique among these movies you’ve mentioned, Sleep Dealer is a bi-lingual film, with the vast majority of the dialogue in Spanish. How did you think about language in the film?

A.R.: We need to know in our guts that we are going into a future that will be multi-cultural. I think we are seeing in the news right now that America might not be the only world power in the future, that English might not be the international language of choice. So, for me, doing a science fiction set in the South and doing it in a language that was not English was fundamental. I’d love to do a science fiction in Nahuatl, or in Tagalog, or in Pashto. The language is just part of a gesture that says, the future belongs to all of us.

I think the situation we’re in is very striking. It is as if you met somebody and you asked them, “What do you want to have in your future?” And they said, “I don’t know. I’ve never thought about it.” In the cinema, that’s what we have for the entire global South. We don’t have any cinema that reflects on the future of the so-called Third World. There’s zero.

Why is it that we’ve seen comedies from the South, we’ve seen romances from the South, we’ve seen action movies from the South? We’ve seen everything but reflections on the future. To me, the first step to getting to the future that you want to live in is to imagine it.