Does Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine hold water?

Published in the Spring 2008 issue of Dissent.

A strange contradiction afflicts nonhierarchical social movements. Those activists who are most hesitant to create formal mechanisms for naming leaders give the media the most power to choose their leaders for them. Certainly this has been the case in the globalization movement, where an anarchist ethos has prevailed. Faced with a vast network of affinity groups, spokescouncils, and local organizations, the news media have been desperate to find a few recognizable figures to present as figureheads. They have thrust a handful of writers and intellectuals into the spotlight—one of the most notable being thirty-seven-year-old Canadian journalist Naomi Klein.

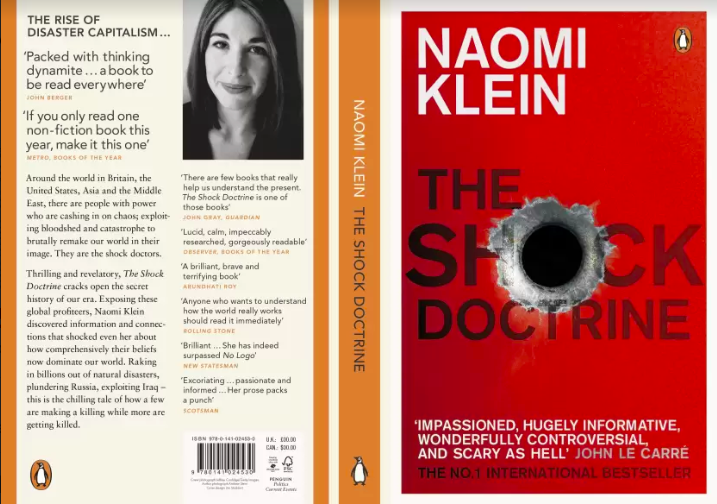

Early on, Klein benefited from an exceptional instance of good timing. Just as her first book, No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies, was going to press, historic protests erupted at the November 1999 World Trade Organization ministerial meetings in Seattle. The anticorporate movement her book chronicled went from being regarded as a loose, underground collection of international campaigns to a bona fide global phenomenon. The book sold over a million copies worldwide.

It was a fortuitous turn, but Klein’s success was not based on luck. She had read the political mood well. In the early 1990s, when she was a student in Canada, Klein writes, “campus politics was all about issues of discrimination and identity.” Doing research at some universities five years later, she noticed a shift. The students’ analysis was “broadening out to include corporate power, labor rights, and a fairly developed analysis of the workings of the global economy.” While other books were starting to argue, in Klein’s words, that “corporations have grown so big they have superceded governments,” she set out to profile the forces of resistance to these corporations. She ended up with one of the most astutely observed accounts available of the motivations, outlook, and demands of the emerging global justice movement.

A wonderfully acute piece of cultural criticism, No Logo is often referred to by journalists as a movement “bible.” This is a lazy analogy: I have never seen a globalization activist hold it up as holy writ, and the tone of the work is more guidebook than manifesto. Antisectarian to its core, the book speaks to both believers and skeptics at the same time, with its colorful examples of life in the new corporate age. Klein tells of how Diesel Jeans salesmen contended that their product was less a piece of clothing than “the way to live… the way to wear… the way to do something.” The work of multinational corporations in this era, she explains, centered on managing their brands rather than manufacturing actual products, which were all too likely made in subcontracted sweatshops in Southeast Asia. Advertisers crept further and further into schools and public spaces. And, preempting real dissent, companies lured hipsters with ironic ads and sold resistance in the form of “Revolution” cola. At the time, all this was revelatory. The book made the environmental campaigns and living-wage drives of the global justice movement seem like eminently reasonable responses.

A good part of Klein’s appeal was the lack of holier-than-thou pretense in her politics. In No Logo, she tells of working as a young adult folding sweaters in an Esprit store in her native Montreal; of how her favorite parts of camping trips with her parents as a child were when the family car passed the molded plastic sign of a McDonald’s or Burger King and she would crane her neck to linger on the cherished icon; of how “by the age of six, my older brother had developed an uncanny knack for remembering the jingles from television commercials and would tear around the house in his Incredible Hulk T-Shirt declaring himself ‘cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs.'” All this created great consternation for her hippie parents, American activists who had fled to Canada to escape the Vietnam War draft.

These experiences helped Klein to develop keen political sensitivities, however. Because she was part of a generation that could viscerally feel the seductive power of the corporate brand machine, she was able to express the fomenting desire to break free of its hold. In the end, she would proudly carry forth her family’s radicalism. Of those who have been elevated as movement leadership in the media spotlight, there are few who serve as more articulate and responsible spokespeople. Despite her growing fame, she has remained resolute in her calls for economic justice, passionate about holding herself accountable to grassroots networks of citizen activists, and fearless in taking on those who defend the privileges of the powerful. All these would prove to be invaluable traits during the Bush years.

* * * * *

NOT LONG after No Logo, Klein published a volume that collected a variety of her “dispatches from the front lines of the globalization debate.” But her next major book did not come for several years. When The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism appeared in the fall of 2007, it clearly belonged to a different era.

The book emerged out of Klein’s reporting in Iraq, New Orleans, and post-tsunami Sri Lanka. Moving among these scenes, she observed a pattern. In the case of Iraq, occupation administrator Paul Bremer followed up on the “shock and awe” invasion by announcing the creation of a radically privatized economy, structured around what The Economist called a “wish-list that foreign investors and donor agencies dream of for developing markets.” Corporations like Halliburton, Bechtel, and Blackwater rushed to cash in, performing many duties that were once seen as core functions of the U.S. military, while Big Oil lustily eyed the prospects. In the case of Sri Lanka, white sand beaches scrubbed clean by the 2004 tsunami were promptly handed over to hospitality corporations to create lavish tourist resorts, blocking small fishing villages from rebuilding. And after Hurricane Katrina, the Heritage Foundation devised a list of thirty-two die-hard neoliberal policies to be implemented in the name of “hurricane relief”—including the suspension of prevailing-wage laws and the creation of a “flat-tax free-enterprise zone.” These were swiftly adopted by the Bush administration.

Klein gives a name to this trend of “orchestrated raids on the public sphere in the wake of catastrophic events, combined with the treatment of disasters as exciting market opportunities.” She dubs it “disaster capitalism.”

“When I began this research into the intersection between superprofits and megadisasters,” Klein writes, “I thought I was witnessing a fundamental change in the way the drive to ‘liberate’ markets was advancing around the world.” As she investigated further, however, she became convinced that the trend had deeper historical roots. Ultimately, she would conclude that “the idea of exploiting crisis and disaster has been the modus operandi of Milton Friedman’s movement from the very beginning.” For at least three decades, she writes, neoliberals have been “perfecting this very strategy: waiting for a major crisis, then selling off pieces of the state to private players while citizens were still reeling from the shock, then quickly making the ‘reforms’ permanent.” This, in short, is “the shock doctrine.”

As a metaphor for the principle, Klein relates the story of Dr. Ewen Cameron’s CIA-funded experiments at McGill University in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The highly unethical Cameron used an extreme program of shock therapy to induce regression and amnesia in his patients, creating a blank slate upon which he could write a new personality. As a form of therapy, it was an abject failure. But the idea proved compelling to CIA interrogators, who later promoted electroshocks as a way of making prisoners, Klein explains, “so regressed and afraid that they can no longer think rationally or protect their own interests.” The victims are shocked into a state of openness.

In the wider implementation of neoliberal ideology, shocks are implemented at the social rather than individual level. In country after country, Klein argues, the initial shock of war, natural disaster, or economic crisis is followed by a second period of shock, in which a set of unpopular neoliberal reforms—privatization, deregulation, and cuts to social services—is rammed through while people are still too confused and disoriented to resist. Finally, in a third period of shock, repression and torture are used to silence those who dissent.

* * * * *

KLEIN USES her shock framework to connect a wide range of events. Moving chronologically, she starts by showing how the implementation of neoliberalism in Pinochet’s Chile in the 1970s followed this model. There, Friedmanite economics, previously considered far too reckless to be implemented, were imposed by a dictatorship shortly after it overthrew the democratically elected Allende government. In Argentina, a military junta implemented a set of economic reforms similar to Chile’s, in the process “disappearing” 30,000 people. Across the ocean, in the United Kingdom in 1982, “the disorder and nationalist excitement resulting from” the Falklands War allowed Margaret Thatcher “to use tremendous force to crush the striking coal miners and to launch the first privatization frenzy in a Western democracy.”

A different type of crisis, hyperinflation in Bolivia in 1985, created a moment traumatic enough for economist Jeffrey Sachs to sell his brand of extreme economic “shock therapy.” This same, all-at-once prescription for submitting to the market was issued in Russia in 1993, its mandates carried out by Boris Yeltsin after he sent tanks against the Russian Parliament and jailed opposition leaders. These are hardly the only examples. Klein argues that from Poland to South Africa to China to the countries affected by the Asian financial crisis, “[t]he history of the contemporary free market… was written in shocks.”

The Shock Doctrine is an ambitious book, an accomplished book, and an important one, too. It makes contributions in several key ways. First, Klein’s talent as a storyteller is on full display. She again shows that she is one of the few writers working in English who can simultaneously write effectively for both mainstream and radical audiences. Regardless of whether one fully agrees with Klein’s overarching argument, her chapters represent highly valuable capsule histories of market expansion.

For instance, there have been numerous retellings of how neoliberalism was implemented in Pinochet’s Chile—Greg Grandin’s Empire’s Workshop, for one, did a fine job of publicizing the tale in 2006. Yet Klein’s version of this story is singularly vivid and well researched. She provides gripping scenes of tragedy—such as when pro-Allende dissident Orlando Letelier is assassinated in Washington, D.C. After a car bomb planted under his seat detonates, “his severed foot [is] abandoned on the pavement” as an ambulance tries futilely to get him to a hospital in time. Likewise, Klein conveys the drama of more mundane events: she shows a group of Chilean-born, University of Chicago-trained economists “camped out at the printing presses of the right-wing El Mercurio newspaper” in the hours before Pinochet’s coup, racing in an adrenaline-fueled push to finish, print, and get to key military officers copies of their “five-hundred page bible—a detailed economic program that would guide the junta from its earliest days.”

Second, the core message of The Shock Doctrine is a critical one. The book, she writes, “is a challenge to the central and most cherished claim of the official story—that the triumph of deregulated capitalism has been born of freedom, and that unfettered free markets go hand in hand with democracy.” Instead, Klein aims “to show that this fundamentalist form of capitalism has consistently been midwifed by the most brutal forms of coercion.” Some critics have taken issue with this argument’s lack of novelty. They argue that anyone who takes a serious look at the development of capitalism over the past several hundred years will notice that violence is a persistent, indeed pervasive, aspect of the creation and maintenance of “free” markets.

Here I stand behind Klein. Granted, one could go back to a wide variety of political-economic classics to illustrate the point that the “free” market has historically required forceful state action to bring it into existence—the work of Karl Polanyi comes to mind as a good first stop. Yet some stories need to be told over and over again. As long as the dominant ideology insists that peace, democracy, and “free enterprise” go together as a harmonious trio, Klein is right that the talents of progressive analysts should be devoted to demonstrating the contrary in fresh and convincing ways.

A third asset of the book is that disaster capitalism, as displayed in Iraq, New Orleans, and post-tsunami Sri Lanka, is no doubt an important recent phenomenon, one that is likely to grow more significant as the effects of global warming increasingly materialize. Klein has done a great service in naming and detailing it.

* * * * *

THAT SAID, it is questionable whether the argument can be generalized to serve as the basis for a broader understanding of the global economy—whether the shock approach can accurately be called, as she claims, “the preferred method of advancing corporate goals.”

The issues Klein addresses in The Shock Doctrine reflect a more general shift in the globalization debate. In the Bush era, the politics on campus have changed once again. While just a few years ago we were frequently told that the nation-state had become obsolete and was being supplanted by transnational businesses, the state has reasserted itself with a vengeance in the wake of 9/11. For student activists, opposing the Bush regime has largely taken precedence over anticorporate campaigning. And for globalization analysts, the challenge has been how to reframe their accounting of the world order to make the state a more central part of the panorama.

The Shock Doctrine deals with this dilemma by melding the state and the market entirely. Klein argues, “In every country where Chicago School policies have been applied over the past three decades, what has emerged is a powerful ruling alliance between a few very large corporations and a class of mostly wealthy politicians—with hazy and ever-shifting lines between the two.” The proper name for this system, she writes, is “corporatism.” She explains that the “acceptable role of government in a corporatist state” is “to act as a conveyor belt for getting public money into private hands.”

In a similar vein, Klein argues that the only motivation that matters in contemporary capitalist politics is greed. Pointing out that Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, and a variety of neoconservative ideologues have deep financial ties with industries that stand to benefit from the “war on terror,” she states that any attempt to divorce their political fervor from their business interests is “both artificial and amnesiac.” She writes dismissively, “The right to limitless profit-seeking has always been at the center of neocon ideology…. With the War on Terror, the neocons didn’t abandon their corporatist economic goals; they found a new, even more effective way to achieve them.”

Stripping down politics to the profit motive will get you a long way in this world. It can be an especially useful corrective when the “crusade against communism” and “battling terrorism” are constantly invoked as noble motives, and when nothing so crass as economic interests are ever admitted. But, needless to say, the move is reductionist.

Klein’s depiction of a monolithic class of politico-corporate elites is not tailored for every political situation. It is not particularly helpful for recognizing and exploiting the differences between Clintonian “free traders,” Republican realists, and neocon fundamentalists. It provides little guidance for understanding what to make of it when the Weekly Standard opposes permanent normal trade relations with China, a key goal of corporate globalists, on human rights grounds. Nor does it allow for distinctions between different sectors of capital—recognizing, for example, that the interests of the vast tourism industry (which is currently furious about how Bush’s War on Terror has adversely affected its business) may not be the same as those of Halliburton. Finally, it denies out of hand that religious conviction or nationalism, independent of commerce, might be forces in influencing Bush administration policy.

Curiously, even though Klein is tightly focused on following the money, her book is not materialist in a way that will satisfy more traditional Marxists. She avoids exploring the structural forces—for example, the post-1973 contraction of the global economy or the declining profitability of core industries—that have shaped the rise of neoliberalism.

Klein’s insights into the use of political shock are probing, but they, too, have limits. When the book’s chronology finally makes it up to the invasion and occupation of Iraq, its argument takes a strange turn. Throughout the volume, Klein frequently invokes the “shock and awe” metaphor. Because of this, readers are led to believe that George W. Bush’s war will represent the epitome of the shock method. In fact, it is where the metaphor starts to unravel.

Iraq has been subjected to every shock imaginable. But rather than producing a state of regression and acquiescence, the onslaught has provoked intense resistance. As deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage is quoted as saying, “The U.S. is dealing with an Iraqi population that is un-shocked and un-awed.” Beyond the ethical and political implications of the botched occupation, it is just plain bad capitalism: “Bremer was sent to Iraq to build a corporate utopia,” Klein writes; “instead, Iraq became a ghoulish dystopia where going to a simple business meeting could get you lynched, burned alive or beheaded.” The author is ambivalent about the lessons. On the one hand, the corporate contractors who fled Iraq en masse had already reaped billions from government contracts, and energy companies still have their eye on Iraq’s oil. On the other hand, the crisis model has been foiled in important ways.

As it turns out, Klein explains, Bush-era disaster capitalism is not really the shock doctrine in its fullest form. Rather, it represents a late, desperate, and especially fanatical manifestation of a system that has been exhausted. After some four hundred pages, this modified thesis is unsatisfying. As Klein’s framework breaks down in Iraq, her regular repetition of the word “shock” starts to seem more like an overworked rhetorical device than a consistent and enlightening analysis.

The Shock Doctrine makes a lot of Milton Friedman’s contention that “[o]nly a crisis, actual or perceived, produces real change.” But there is no reason why this idea is inherently objectionable from a progressive perspective. In the U.S. context alone, one could argue that the shock of the Great Depression created the New Deal. Or that the civil rights movement, with its resolute nonviolence, prompted Bull Conner to unleash his attack dogs and fire hoses, creating a televised crisis that shocked the nation into action. Indeed, only the most stubbornly gradualist theory of social change would overlook the role of various “shocks” in sparking revolt.

* * * * *

IN KLEIN’S READING of the Bush years, it would be easy to forget that there exists a commercial world beyond the realms of homeland security, the defense industry, heavy construction, and oil. She contends that a “homeland security bubble”—a sector estimated in a December 2005 Wired magazine article to be worth as much as $200 billion—saved the American economy from a much deeper crash after the dot-com bubble burst. The runaway U.S. housing market, ballooning credit card debt, and China’s willingness to continue propping up the dollar receive little, if any, mention. Similarly, many of the key corporations featured in No Logo—such as Nike, Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, Microsoft, Disney, and Starbucks—almost disappear from her narrative, as if they have ceded the global economy to Halliburton, Bechtel, Exxon, and Lockheed Martin.

The result is a significantly revised vision of the nature of modern capitalism. “Democratic socialism, meaning not only socialist parties brought to power through elections but also democratically run workplaces and landholdings,” was “never defeated in a great battle of ideas, nor were [these ideas] voted down in elections. They were shocked out of the way at key political junctures,” she argues. Certainly, there is truth to the idea that many populations dubious of neoliberalism have been tortured into submission. But there is also something missing from this picture.

In The Shock Doctrine the insidious, seductive powers of multinational capital have vanished. Absent them, there is little to account for the local elites in the global South who are peacefully co-opted into supporting the American model, the insecure middle classes who align themselves with the upwardly mobile rather than with movements of working people, or the underclass of aspiring consumers who have been charmed by the alluring promises of Hollywood and Madison Avenue—all people who play much more central roles in other chronicles of the spread of market ideology. Nor is there much room left in the analysis for those children of the North who, by the age of six, already sing corporate jingles and plead for fast food—those who have never been tortured by the state but have felt an embrace that, in its own way, is plenty shocking.