The President’s trip south of the border will do little to sway a region that is demanding fairer economic policies.

Published in Tom Paine.

Whether out of a desire to escape his record-low approval ratings at home or a hunger for Mexican tamales and Brazilian rice and beans, George W. Bush is making a run south of the border. This week the president will stop in Brazil, Uruguay, Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico—making his longest-ever official visit to Latin America. Taking place at a time when feelings of animosity toward the United States are widespread, the tour will serve as Bush’s most concerted effort yet to improve relations with the region.

What are the odds that his travels will do anything to reverse anti-yanqui sentiment? Not good. Our neighbors to the south have ample reason to be resentful. They have suffered from a White House approach to Latin America that is based on a fundamentally flawed conception of U.S. national interest.

In a speech on Monday, the president contended that his trip will signal a new, more caring attitude toward Latin America and its people, including the large populations that live in poverty. But actions speak louder than words. Few things say more about the Bush administration’s outlook on the region than the appointment in February of John Negroponte to Deputy Secretary of State. Negroponte was an ardent Cold Warrior who served as Ambassador to Honduras for a stretch in the 1980s when the country became a haven for death squads and CIA-funded Contra mercenaries. Negroponte’s promotion made it ever more clear that Bush policy is being defined by Reaganite reactionaries whose conception of international relations is based on an outdated notion of U.S. power and Latin American acquiescence.

The White House continues to champion flawed economic policies for the region and seems only to appreciate democracy when Latin American elections put pro-U.S. cronies into office. This rearguard policymaking has little chance of swaying a region that is growing increasingly independent. A foreign policy that truly values democratic processes and shows genuine concern for the region’s poor would be far more likely to win allies than the diplomatic strong-arming and electoral meddling that has so often marked U.S. relations with our southern neighbors. Such a policy, however, remains a distant dream.

* * * * *

Fates Worse Than Neglect

The failure of past U.S. policy is not merely a problem for the current administration; it also presents a challenge for the Democrats. Before gaining a majority of seats in Congress, the Dems claimed that the President had failed to pay enough attention to Latin America. In 2004, John Kerry argued in his campaign that Bush’s Latin America policy was marked by “neglect, failure to adequately support democratic institutions, and inept diplomacy.” Since then, various Democrats have repeated the charge, using the language of “neglect” whenever Latin America comes up.

Yet now that the Democrats hold more power, this observation no longer suffices as a position on hemispheric affairs. Under President Clinton, Democratic policy toward Latin America focused on promoting an aggressive “free trade” agenda and pushing poor countries to pursue a corporate-friendly path to development. Clinton, after all, was the president who ushered the North American Free Trade Agreement through a Democratic-controlled Congress. Clinton further envisioned spreading NAFTA throughout the hemisphere with a Free Trade Area of the Americas. (Thankfully, the FTAA has been buried in recent years by waves of popular resistance, as well as disinterest from the new generation of progressive presidents that has won office in countries throughout the region.)

Clinton-style economic neoliberalism failed to benefit the majority of Latin Americans, and this failure is at the very root of the region’s recent swing to the left. Policies like privatizing public industries, cutting government social spending, and deregulating financial sectors may have paved the way for multinational corporations to spread. However, they produced two decades of abysmal GDP growth in Latin America. While a small elite grew fantastically wealthy, most people in the region saw few, if any, improvements to their standard of living.

The 1990s were supposed to be years of globalizing prosperity. Yet the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported in 2001 that “nearly 36 percent of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean lives below the poverty line—the same proportion as a decade ago.” This number greatly understates the number of citizens who are scraping together only meager livelihoods or relying on money sent back from family members who have migrated north. Moreover, the wealth that has been produced in the region has not been shared equally. As a 2003 World Bank report explains, “The richest one-tenth of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean earn 48 percent of total income, while the poorest tenth earn only 1.6 percent.”

Of late, economic elitism has been smacking up against the popular vote. Comfortable candidates promising pro-U.S. policies are learning that it’s hard to win elections with only that richest one-tenth of the population behind you. The Latin American populace is clearly fed up with neoliberalism’s lackluster results, and rightly so.

Democrats who propose a return to Clinton-era policy that values “free markets” above all else have missed this key lesson. They may vow to pay more attention to Latin America, but there’s no guarantee that such attention will be a good thing. Given their past relations with the United States, Latin Americans are all too aware that there are worse things than neglect. It is incumbent upon the Democrats to offer a positive vision of America’s national interest that can transcend both Bush’s Cold-War-minded approach to hemispheric affairs and the flawed corporate globalization still favored by segments of the party.

* * * * *

Beyond Hugo Chávez

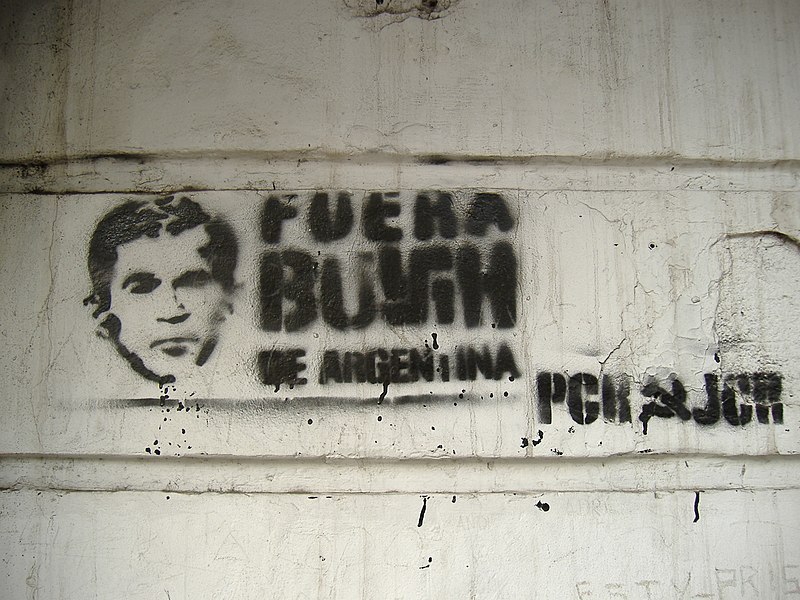

One of the key pressures motivating U.S. action to improve its image in Latin America is the rise of Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela as a formidable ideological rival. The most outspoken of the left-of-center Latin American presidents, Chávez has cemented his popularity by using the windfall of high oil prices to fund anti-poverty initiatives in Venezuela and beyond. He has sent upwards of $16 billion in aid abroad in recent years, with especially significant infusions of resources going to Bolivia and Argentina. Chávez has gone so far as to send subsidized heating oil to families that might otherwise go cold in poor sections of New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other American cities.

No doubt, there are criticisms to be made of Chávez’s style of governing, but the rabid Bush White House and the mainstream newspapers that have followed its lead have lost all sense of proportion in their outrage about Venezuela’s “checkbook diplomacy.” The denunciations make it sound as if Venezuela could have no humanitarian vision whatsoever about helping those in need, and as if the money that the U.S. sends overseas as foreign aid is offered out of pure, untainted benevolence. Given the Bush administration’s well-established ideological preoccupation with shrinking government and its distaste for social safety nets, it has little credibility to speak out about the proper way to deploy the profits from oil resources. As it is, Venezuela’s example is a powerful and persuasive one in a region that is ready for more equitable economic policies.

Chávez has charged that the intent of Bush’s trip is “to divide Latin America.” He’s right. A main White House strategy for handling newly progressive governments has been to denounce the vaguely ominous dangers of “populism” and try to separate “good” Latin American leftists from “bad” ones. Bush has selected to visit countries where he thinks he can pull leaders away from a Chávez-led regional bloc.

But the real issues go far beyond Chávez, and those who want to pin our country’s image problem in Latin America on a single antagonist ignore a central reality: Being on the U.S.’s good side hasn’t been paying off too handsomely. In Brazil, where President Lula da Silva has worked to maintain good relations with the IMF and U.S. Treasury by largely adhering to neoliberal economic mandates, GDP growth over the past four years has averaged only 2.6 percent. This places Brazil alongside Haiti and El Salvador among the hemisphere’s slowest growing economies. As Lula continues to structure his government’s budgets around massive debt payments to wealthy lenders, he is left with little funding to devote to his flagship anti-hunger program and other social initiatives.

Argentina, by contrast, has seen a 45 percent increase in economic growth since 2002, when it broke with the Washington Consensus, forced creditors to restructure its debt, and began taking a hard line with the IMF, whose recommendations had helped to produce that country’s profound economic crisis in 2001.

__________

Research assistance for this article provided by Sean Nortz. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.