A review of The Children of NAFTA: Labor Wars on the U.S./Mexico Border.

Published in the Winter 2004 issue of LiP Magazine.

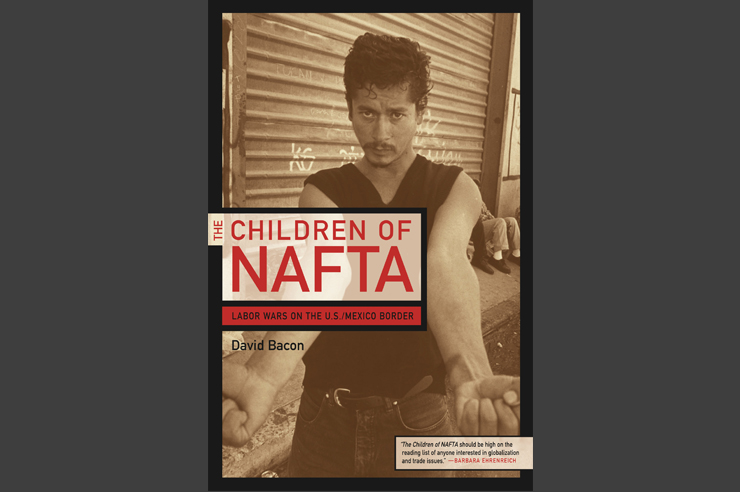

The Children of NAFTA: Labor Wars on the U.S./Mexico Border, the first book from labor journalist and photographer David Bacon, provides an important remedy to debates on trade policy mired in economic generalizations. Bacon is a reporter who thrives on the specific. His book is filled with interviews with workers, mainly from the border maquiladoras of Baja California, who articulate the human consequences of treaties like NAFTA.

“We can’t live if we don’t all work,” one twelve-year-old boy, laboring alongside his parents, tells Bacon in “the tone of someone explaining the obvious.” Indeed, explaining what should be obvious is something that Bacon and his interviewees do with great skill. Typical conditions in the border factories are horrendous, they tell us, and the labor “side agreement” to NAFTA—the rider meant to protect workers’ rights—has done nothing to improve them.

Exhibit A is Han Young, a Mexican factory making chassis for Hyundai cars, where workers who tried to form an independent union were not only fired, they were blitzed by the local SWAT team and chased for months as fugitives. In response to the workers’ grievances, the National Administrative Office (NAO)—the labor board created under the NAFTA side agreement–merely mandated a seminar on labor conditions.

Then there are the jonkeados—the junked workers. “They were workers who became so sick, so chronically disabled” from inhaling glue fumes and solvents at two auto trim factories, “that they were given special jobs” at the plant. One father testified that, as a result of his condition, his baby son was born with no kneecaps and an enlarged heart, yet the doctors would not let him donate blood for the infant, since they said his “blood was contaminated with drugs.”

These workers held out hope that their NAO complaint would force governmental action because it focused on health and safety violations, rather than unionization rights. Instead, their case reinforced a distressing pattern. “Hearings were held. Workers testified, sometimes at considerable risk. The NAO… concluded… that serious violations of the law had occurred,” Bacon writes. “And then—nothing.”

This lack of enforcement, Bacon’s interviewees contend, results from the very logic of free trade, which demands busted unions and junked, disposable workers. “What makes our country attractive to U.S. [businesses],” says Mexican professor Gema López Limón, “are low wages.”

David Bacon developed his clear-eyed view of global economics during some two decades as a organizer for unions like the United Farm Workers (UFW) and the United Electrical Workers (UE), organizations with long histories of independent radicalism. He turned to labor journalism full time in the early 1990s, just before a slate of reformers took control of the AFL-CIO and began an effort to reverse labor’s decades-long decline and to reconnect the federation with its social movement roots.

In this context, Bacon has often looked prescient. Years before the AFL-CIO reversed its previously misguided position on immigration policy in 1999, Bacon was documenting how INS raids were being used by employers as anti-union tools and arguing that labor needed to be at the fore of the effort to protect the rights of immigrant workers.

In The Children of NAFTA, Bacon notes the major shifts within the AFL-CIO, yet he seems to hold these organizational developments at arm’s length. Emphasizing the bottom-up contributions of workers organizing on the frontlines, he avoids discussing how different unions are making institutional interventions to change how the U.S. labor movement is structured and how it deploys its resources on a national level.

Since the focus of Bacon’s book is on production jobs that have fled south of the border, it is understandable that he gives manufacturing workers the bulk of his attention. His chapter on “transplanted expectations,” however, in which he brilliantly explains how immigrants are bringing “their culture, traditions, and forms of social organization” to U.S. movements, is glaringly bereft of reporting on immigrant janitors, hotel housekeepers, and laundry workers. Unions in the fast-growing, low-wage segments of the economy’s service sector have lately waged the most aggressive campaigns amongst immigrant workers–often scoring impressive contracts–and have most boldly pushed the AFL-CIO to redirect its resources to take on corporate titans.

Lacking these more heartening campaigns, The Children of NAFTA is a book filled with sad endings. Direct action sometimes secures gains for maquila workers, in one case winning “buses to and from work, a ten percent pay bonus, and uniforms twice a year.” But more often unions in the border factories are busted, strikes are broken, and international hearings offer no recourse.

Journalists tracking the resurgent labor movement’s efforts to find a successful strategy to take on multinational corporations will have to learn from Bacon’s dogged local reporting–from his vivid evocation of the experiences of those who stand up for dignity in their working lives. But they will also have to show the institutional processes by which labor’s internationals and federations are slowly being remade to build new power. We will need more than David Bacon, but we will also need many of him.