A series of post-9/11 reflections.

September 2001

Shortly after 9 AM last Tuesday, when we still thought the attack might be a freak accident, I walked down the street in my Brooklyn neighborhood to Fort Greene Park. There, from on top of the hill, you had a clear view over the river to where the World Trade Center stood. On this day, that meant you clearly saw one, then two flaming Towers, perfectly framed. I thought of bringing my camera to document the unreal scene, but I soon found that the view was hardly unique. In fact, it was identical to those shot by hovering helicopters and shown everywhere on TV.

Only by turning around did I see the more singular and arresting photo. Already early that morning, a crowd of people had gathered on top of the hill. No one talked much; it was not a social affair. They all stood facing the same direction, eyes locked. With the low-angle morning sun illuminating their bodies, they glowed, looking as if they watched a Martian saucer touch down in lower Manhattan.

* * * * *

1.1

That first morning, facts led fluid and unconfined lives. The television news reported bombing on Capitol Hill, fire on the Washington Mall, eight separate planes hijacked. These assertions would stand for some time, then fade away without proper correction or disavowal. The accepted version of events that emerged from this confusion simply asserted itself by strength of repetition, and not by contrasting itself with previous reports.

Some confusion results naturally in trying to make sense of bewildering events. Other confusion is political.

During the earliest speculation of who and why, television commentators mentioned the demonstrations against the IMF and World Bank, scheduled for the end of the month in Washington, DC. In doing so, they insinuated that protesters might be responsible for the terrorism. This infuriated me: The warped security mythology about violent protestors in places like Seattle had fully reversed reality. It was as if the police officers had been the ones who dressed up like butterflies and choked through clouds of tear gas. As if the protesters had been shooting the rubber bullets and pepper spraying riot troops, troops locked together and seated cross- legged in the middle of the street. As if the Italian protester, 23-year-old Carlo Guiliani, had delivered a bullet, rather than taking one in the face.

As I calmed down, I realized that perhaps I overreacted to the passing implication of global justice protesters. Nevertheless, this served as my first inkling that now, amidst the bipartisan declarations of war, words would bear a different relation to the truth.

In the official response to the attacks, as on TV, information would go missing and specifics would shift. The point that holds steady is the war.

Friday’s New York Times featured a biographical profile of Osama bin Laden. Astonishingly, while it describes his Cold War guerrilla efforts against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, it all but excises any ties to the United States—erasing past CIA support for bin Laden’s activities. A story on the same page talks of President Bush making diplomatic calls in preparation for his own potential attack on Afghanistan.

These items recall Orwell’s descriptions of the shifting alliances between Eurasia, Oceania, and Eastasia; in the states of 1984, who one counts as friend or foe may reverse abruptly, but officials eliminate any inconvenient history by never making “mention of any other alignment than the existing one.”

According to the Times, whose “deep knowledge” of Afghanistan will President Bush consult in his invasion? Russia’s, of course.

* * * * *

1.2

My partner Rosslyn organizes for the Hotel and Restaurant Employees Union, Local 100. Members of the union include the employees of Windows on the World, the restaurant that sat atop Tower One of World Trade Center, famous for its majestic views of the city.

On Wednesday, September 12, when much of the city was shut down, Rosslyn went in to work. Throughout the day, people filled the union hall. Workers from Windows who had not been scheduled to work Tuesday wept alongside families who were missing a loved one. After a few hours, everyone came together to begin a painful reckoning.

Members worked slowly through a list of employees on the disastrous morning’s shift. As they read each name, they shared any information they had about their co-workers: who had called in sick that day; who had been running late to work; who might be in the hospital. Eighty workers are still missing.

In the following days, people from other union shops in lower Manhattan also came into the office, worried about being out of work and being able to support their families when the building that housed their cafeteria had suffered structural damage. As they met the grieving families, or learned that a fellow activist had not been accounted for, these initial concerns no longer seemed as important.

“None of our members who was working that day walked out of the building,” one organizer said to a New York Daily News reporter present at the Wednesday meeting. At the time, he thought that three or four of them might have been dug from of the rubble and taken to the hospital. “But no one got out on their own two feet.”

* * * * *

1.3

On Friday evening, September 14, I went to a vigil on 14th Street, in Manhattan’s Union Square. As the sun set, more and more New Yorkers pressed into the square. I knew some friends intended to come to join with a South Asian arts organization and with other groups calling for peace. I looked amongst the people carrying signs saying, “Islam is not the Enemy” and “Justice not Revenge.” But it was impossible to search out individuals, or even to determine where the group ended. The density of the square merged everyone into a single mass.

All around people held lit candles, and a choral group nearby began leading songs, beginning with “The Star Spangled Banner” and “God Bless America.” Where I stood, some felt uneasy, fearful of the direction in which this patriotism might lead. I remembered Rosslyn telling me of her train ride home on Tuesday, when an apparently drunken man on the subway ranted incessantly: “They’re fags. They’re a bunch of fags. Their women are whores. I fought in Vietnam, for the USA. One hundred percent American. Those Palestinians are a bunch of fags.”

But at the vigil, the tension quickly broke. The choir also sang peace songs: “We Shall Overcome” and “This Little Light of Mine.” It became clear that the content of the songs was not as important as their familiarity, their place in a shared musical canon. Indeed, people responded perhaps most enthusiastically as we joined in singing “New York, New York.”

I live in a house with seven other people, where we can gather and discuss the unfolding events. Many others have come to join us, beginning already on Tuesday morning. Because our neighborhood is not far from the water, people who walked across the Brooklyn Bridge from the enflamed financial district stopped here to rest, carrying reports from the scene and bits of the morbid ash on their clothing.

Hearing their many stories, I appreciate the rare and fortunate nature of the exchange. I learn how easy it is to be isolated in front of the television, and how difficult to escape settings in which everyone seems to be calling for blood.

The vigils are important for this reason. People experience a form of public response distinct from the Washington politicians’ fevered reactions. They engage in a dialogue about varied experiences of tragedy, and thus resist moves to reduce these into a vicious form of nationalism. Mayor Guiliani has helped to establish this alternative as a form of official response, showing a remarkable humanism with statements focusing on the effort to save lives and denouncing acts of hatred.

In our house, fear of anti-Arab violence is not an abstraction. Thursday morning I sat at the breakfast table as one of my housemates, a columnist for Midday in Bombay, lamented having an Arabic last name: Ansari. In writing his column Tuesday, he contemplated how, amidst a rising tide of xenophobia, he would have to strategize to “keep his face and accent from the streets.” He began that same day, by shaving off his beard.

* * * * *

1.4

A few years ago I served as a speechwriter for Oscar Arias, the former President of Costa Rica and 1987 Nobel Peace Laureate, who toured regularly to lecture on issues of demilitarization, arms control, and globalization.

At one point, I was working on a speech for an upcoming event at a college with a conservative reputation, where faculty members migrated between the campus and the Department of Defense. We knew that, even in the best of circumstances, there would be some unsympathetic listeners in the audience. But to compound the problem, the event came on the heels of one of our frequent bombings of Iraq.

I remember that the environment felt hostile, filled with clamorings of war. I wrote into the speech a quote by Martin Luther King, which I had recently read in his 1967 work, Where Do We Go From Here?

“The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral begetting the very thing it seeks to destroy. Instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may murder the liar but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence you murder the hater, but you do not murder hate… Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

When Don Oscar and I sat down to read over the material, he quietly reviewed the quotation. To my surprise, he grew angry and turned toward me accusingly:

“That passage is very important,” he scolded. “Why haven’t we been using it before?”

* * * * *

Chapter 2

April 2002

“Dead or alive” militarism has the advantage of being simple, but it has the notable downside of making the world a more dangerous place. President Bush rarely lacks zeal in expanding his “Axis of Evil” headhunting. Were it not for the opposition of the entire Arab world as well as many European allies, the U.S. would have launched a new attack on Iraq weeks ago. And even this reason for restraint may not have kept the Administration at bay, had not the conflict between Israel and Palestine inconveniently flared up.

Regardless of whether Bush’s staff could articulate a convincing anti-terrorist rationale for a new campaign in Iraq, their refusal to submit evidence for international review, their flimsy coalition-building, and their macho swagger alienate citizens throughout the international community. Already the arrogant rhetoric of “infinite justice” has left millions abroad who criticize U.S. military interventions to stew in their resentment.

In protests outside the headquarters of the World Bank signs reading “More World, Less Bank!” accompany calls of “No Blood for Oil.” Progressives are not the only ones to see the connection. At Fall 2001 meetings of the World Trade Organization in Doha, Qatar, American Trade Representatives argued that “free trade” stands with national security at the fore of national concerns in foreign relations. The need to satisfy the United States’ insatiable thirst for oil indeed remains a key unspoken motivation behind Bush’s drive to launch a new crusade in the Middle East. And domestically, many conservative observers draw links as they describe both anti-corporate and anti-war demonstrations as unpatriotic and even treasonous.

Nevertheless, protests will grow throughout 2002, as the invasion of Iraq is postponed.

* * * * *

Chapter 3

February 15, 2003, is likely the largest day of coordinated international protest in history.

Starting from within view of the United Nations’ headquarters, a wall of faces stretched some twenty blocks up Manhattan’s First Avenue. The antiwar rally then widened to cover over large sections of Second and Third Avenues as well. Whether the crowd size was closer to the pessimistic 100,000 estimated by authorities or the 400,000 claimed by organizers, two facts hold true: The demonstrators’ presence in New York was massive, and still it made up only a fraction of the weekend’s global mobilization against an invasion of Iraq.

The Los Angeles Times reports that at least a million people showed up for the largest ever march in London, two million rallied in Spain, 500,000 in Berlin, and 200,000 in Damascus, Syria. Another couple million demonstrated in Rome, and over 150,000 turned out in Melbourne, Australia, according to the Associated Press. Reuters says that more than six million people in over 350 cities across the globe joined in protests. Activists report well over ten million people.

Indian writer Arundhati Roy helped to articulate the source of this widespread outrage. “The Bush Administration has launched a two-pronged attack,” she said in a telephone call broadcast through the streets of New York. In addition to its military maneuvers in the Middle East, Roy argued, the White House has commenced a separate attack “on the intelligence of the human race.”

It amazes me how thin a veil President Bush has kept over his plan for “regime change.” Of course, the presentations given at the UN by Secretary of State Colin Powell speak of disarmament rather than the selection of new leadership in Baghdad. But the idea is hardly hidden. The White House suggests elaborate plans for the post-war governance of Iraq. And it has given the headhunt for Saddam Hussein, a brutal but petty thug, an importance that overrides concern for our economy, the need for international cooperation, and even the capture of Osama bin Laden.

In the context of global protest, those who demonstrated in New York, as well as some 200,000 who gathered in San Francisco on Sunday, committed a uniquely pro-American act. They said that we, too, are appalled. They distinguished the fundamental decency of the American people from the renegade regime now in Washington. They refused to accept assassination as a national virtue. And they asserted that the way to overthrow tyrants is through movements for free speech, democracy, and human rights.

Few protest signs were as succinct and as significant in this respect as one held by a woman in front the Dixieland band that animated a carnivalesque procession of Bread and Puppet activists from Vermont. Her sign said simply: “Americans Against War.”

* * * * *

3.1

Several factors conspired to chill dissent in New York. A high of 24 degrees on Saturday, coupled with biting winds, assured that activists seeking warmth would keep nearby delis and news stands filled. In the weeks before the protest, city authorities battled organizers over permits. They provided a rally site only a few days before the event, creating confusion about whether would-be demonstrators would even have a legal place to meet. Authorities never granted sanction for a march on the UN.

The “Code Orange” terror alert also created uncertainty in the city as the weekend neared. Friday night in the subways, I was surprised to find soldiers in full fatigues carrying machine guns. It is something I grew accustomed to when living in Central America, but never expected to see on my trip home to Brooklyn. I wondered if the rally would be similarly militarized.

The next morning, however, the soldiers were gone. Saturday at 10:30AM is not normally a peak hour for the trains, yet I stepped onto a subway car filled with people wearing buttons and carrying signs. Rally planners could foretell with relative accuracy how many busloads were coming in from out of town. But it was the unpredictable local turnout that would ultimately determine the size of the event. “New Yorkers are the ‘x’ factor,” one United for Peace and Justice organizer said to me earlier in the week. The packed subways eliminated doubt that the city had responded.

Having been denied the right to assemble and process in an orderly fashion, the attempts of various groups to get to the rally site themselves became marches. “Feeder” protests snaked through Manhattan’s streets, deploying from all corners. Puppeteers gained momentum walking alongside Central Park, teachers set out from St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and the “Militant Mothers Bloc” gathered between the two stone lions that guard the New York Public Library. There was a march for everyone, from the Interfaith Ministers for Peace to students down from New Haven, who yelled, “Bush’s war is going to fail, kind of like he did at Yale.”

The police bid to deny official space for these processions produced a traffic nightmare. On many streets, cars stood still for hours as marchers swarmed around. Next to one vehicle, still running its engine, activists chanted, “Hey, Hey. Ho, Ho. SUVs have got to go.” Apparently oblivious to how such a vehicle might have been treated in a European demonstration (one car was reportedly overturned in the Athens protests on Saturday), the driver shot perturbed glares at those who wrote anti-war slogans in the dust on his hood.

Organized labor served as an important constituency in the rally. Unions ranging from the City University’s Professional Staff Congress to the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) sent sizable delegations. The healthcare workers union, 1199, went so far as to provide United for Peace and Justice with an office in its 42nd street building. Its politically powerful President, Dennis Rivera, addressed the rally as a featured speaker.

A key message coming from local labor representatives, as well as the national Labor Against the War coalition that New Yorkers helped form, was conveyed by a sign reading, “We Can’t Afford to Rule the World.” Many argued that at a cost that will run over $100 billion, this “preemptive” war in fact undermines the economic security of working people in this country.

Diverting attention from the recession and maintaining a focus on foreign affairs has thus far served the White House well. Some critics have suggested that the Bush Administration’s decision to announce a high terror alert for only the second time since the 9/11 attacks may have been politically motivated. “I think the high terrorist alert is part and parcel of gearing up for war,” said Bill Dyson, a State Representative from Connecticut, as he joined the New York rally. “They’re trying to scare the hell out of everyone and create hysteria.”

I have argued a different position. We have little reason to doubt that many dangers are real, because the Bush Administration’s unilateralist adventures abroad have succeeded in creating a more perilous world.

In either case, we face a dystopian situation: Those in power are able to thrive off of “combating” the same dangers that they busily cultivate. It is a state of perpetual war.

For New Yorkers, the added insult is that much of this is done in our name. My indignation about the exploitation of the city’s grief as a justification for war was rekindled when Angela Davis spoke from the rally’s podium. Davis contrasted the “march of fear”—a stream of people rushing to the hardware store to buy duct tape and plastic sheeting—with the “march of courage” taking place in cities throughout the world.

This rhetoric appealed to me because it mirrored two different types of patriotism that emerged after 9/11. Following the attacks on the World Trade Center, people in New York came together to honor the heroic acts of public safety workers, to assert our commitment to democracy, and to affirm the strength of our communities. Those residents who came out of their apartments to flood Midtown on Saturday recalled the distinctive sense of national community that swelled in the city almost a year and a half ago. Such feelings contrasted sharply with the statements of nationalism coming from Washington, DC. Those were phrased in fundamentalist tones, and claimed our grief as a call for vengeance.

The warlike sentiment may have dominated of late, ruling over a smirking State of the Union. But this weekend, New York City prevailed.

* * * * *

3.2

On Friday, February 14, I spoke with Ben Waxman, a senior at Philadelphia’s Springfield Township High School, one of over 150 schools planning for a national student strike on March 5. “A lot of the kids in my school enlist in the military to get money for college. They come up to me and say, ‘Ben, I don’t want to get shipped to Iraq.’ They want to stop this war.” Waxman explained that “It’s mostly some teachers and administrators that are against us. They say, ‘Saddam Hussein is Hitler.’ And, ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about.'”

The response in Congress to the American people’s skepticism about invasion bears much in common with the paternalism of those high school authorities. “There is no debate, no discussion, no attempt to lay out for the nation the pros and cons of this particular war… This chamber is hauntingly silent,” said Robert Byrd (D-WV) in a recent speech before the Senate. It appears that little will stop President Bush from having his invasion.

It is in these times when protest seems the most futile that it is perhaps the most important. An Associated Press story released Saturday reads, “Rattled by an outpouring of anti-war sentiment, the United States and Britain began reworking a draft resolution… Diplomats, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the final product may be a softer text that does not explicitly call for war.”

A “softer text” was not the demand of the individuals who demonstrated this weekend, nor is it enough to stop a war. Yet such a document provides an unusually sudden acknowledgement of the ability of protest to influence those in power. And it carries a reminder of a vital tradition in democratic political life: When the official avenues of discussion have been closed, democracy demands dissent.

* * * * *

Invasion

Before the invasion of Iraq, as part of the “Cities for Peace” campaign, some 140 U.S. communities passed antiwar resolutions, including large cities like Chicago, Detroit and Los Angeles, as well as small ones like Telluride, Colorado and Salisbury, Connecticut and Des Moines, Iowa.

Early in the morning of March 20, 2003, the day after the war began in Iraq, activists descended en masse on the San Francisco financial district. Protestors tied up the main thoroughfares and blocked the entrances to major office buildings, acting “like sand in the gears,” as one headline in The San Francisco Chronicle read. A mock construction crew closed off a highway ramp with orange cones, road flares, and “Men at Work” signs. After the first day, Alex Fagan, San Francisco’s Assistant Chief of Police acknowledged the historic proportions of the actions. “This is the largest number of arrests we’ve made in one day and the largest demonstration in terms of disruption that I’ve seen,” he said. Protests continued in force for another three days.

* * * * *

Chapter 4

May 2003

Since the invasion of Iraq has ended, a tone of vindication and bravado has seeped into the national mood. Television newscasters and the Department of Defense agree: America is delighted. Soldiers are giving high-fives. Those of us who opposed the president and his generals should be ashamed in the face of a brilliantly successful war.

There is one question, above others, that this prevailing self-satisfaction works to silence. Amidst the atmosphere of recrimination, few will risk asking, “What was the cost?”

On televisions overseas, the Marine blitz and Air Force bombs extracted a human price. While Donald Rumsfeld’s talking head became the singular icon of war in the United States, the rest of the world held up photos of Ali Ismaeel Abbas, the 12-year-old boy who lost his parents and eight other relatives, along with both of his arms, in the bombing of Baghdad.

No doubt some have exploited such images for propagandistic purposes. No doubt the pursuit of carnage at times became tasteless sensationalism. But what was the impact for Americans of seeing so few, if any, of those who died?

There are estimates available of the number of civilians killed in the war. A group of 19 volunteers in England, the creators of a Web site called “IraqBodyCount.net,” estimate that there were a “minimum” of 2,050 deaths as of late April, when the actual invasion ended. This total reflects the lowest numbers provided in news reports of deadly incidents. A more complete tally would have to add the hundreds, maybe thousands, whose deaths were never reported by any source—those buried quietly in the rubble, or those who were wounded and later died in one of Iraq’s overflowing, and ultimately looted, hospitals.

No country, “coalition” or otherwise, has undertaken this reckoning. “A Swiss government initiative launched in the middle of the war,” says John Sloboda of IraqBodyCount, “was abandoned under political pressure.”

* * * * *

4.1

The dilemma this presents is an old one, and a dangerous one, too: What is the weight of a life? How many before it matters? Few can offer good answers. Those who look only at the bloodiest moments of war discount other lives. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqi citizens died as a result of the decade-long sanctions, for which Saddam Hussein bears much culpability, but which the United States had the power to lift all along. Many more would have died if sanctions were prolonged. And we have no way to know how many will be killed in future invasions inspired by Iraq’s conquest, or in resultant acts of retribution.

Washington, of course, kept careful track of the 166 U.S. and British troops killed in action. It shunned, however, the idea of a civilian body count. Many journalists, particularly on television, took this official position as their marching orders.

Even in the most responsible of our newspapers, one idea became a mantra: “a precise number [of civilians who were killed] is not and probably never will be available,” said The New York Times. “The final toll may never be determined,” said The Washington Post. Again and again, reporters noted the difficulty of making an exact tally.

It was, on face, a statement of humility, an honest acknowledgement of the chaos inherent in military conflict. Yet, at some point, this tendency—this refusal to count, or to even try—grew into something else.

It became a form of political denial.

* * * * *

4.2

The rare dispatches that scratched through the surface of the government’s stance on civilian deaths revealed a human side of war—in which young soldiers feared for their lives and relied on quick, difficult decisions—but also, at the same time, a startling desensitization to human life. In one oft-cited report by The New York Times, a Sergeant Schrumpf recalled an incident in which Marines fired on an Iraqi soldier standing among several civilians. One woman was killed. “I’m sorry,” the sergeant said, “but the chick was in the way.”

Another Times reporter wrote of a situation in which Marines attacked a caravan of vehicles approaching them from the distance, not knowing if these might be filled with enemies or, as it actually turned out, with innocents:

“One by one, civilians were killed. Several hundred yards from the forward Marine positions, a blue minivan was fired on; three people were killed. An old man, walking with a cane on the side of the road, was shot and killed. It is unclear what he was doing there; perhaps he was confused and scared and just trying to get away from the city. Several other vehicles were fired on…. When the firing stopped, there were nearly a dozen corpses, all but two of which had no apparent military clothing or weapons.

“Two journalists who were ahead of me, farther up the road, said that a company commander told his men to hold their fire until the snipers had taken a few shots, to try to disable the vehicles without killing the passengers. ‘Let the snipers deal with civilian vehicles,’ the commander had said. But as soon as the nearest sniper fired his first warning shots, other Marines apparently opened fire with M-16s or machine guns….

“[A] squad leader, after the shooting stopped, shouted: ‘My men showed no mercy. Outstanding.'”

* * * * *

4.3

The number of civilians killed does matter, if only to remind us that invasion is not a video game. It matters, because it shows that however sophisticated its tools, war will always claim its “collateral damage,” its innocent bystanders.

A callous indifference toward such lives is not limited to the sergeants and squad leaders on the front lines. It is the position fostered by a government that does not count its victims, even as it lines up more conquests: next Syria, then on to Iran.

It is an attitude that survives outside of wartime, guiding our prejudices against those living in countries whose names we never learned to pronounce, countries that our shock-jocks call “turd world” nations.

In order to break the cycle of war and deprivation, hatred and terrorism, the United States some day must start counting not only the dead from this conflict, but all those whom we perpetually disregard. And it must start holding itself accountable to them. For as it does, we will learn that this is not a matter of two thousand, or even two hundred thousand.

The majority of this world will rise to be counted.

* * * * *

Chapter 5

July 4, 2003

The news, simply put, is that the world hates us. Less than two years ago, following the attacks of 9/11, outpourings of sympathy for the United States flowed from around the globe. Yet those in power in Washington have swiftly converted that goodwill into distrust and contempt.

Poll results released by the Pew Research Center in the first week of June verified the fears that critics of President Bush’s military adventurism voiced all along. “Anti-Americanism has deepened, but it has also widened,” said Pew director Andrew Kohut. Not only has negative sentiment about our country intensified in places like Turkey, Indonesia, and the Middle East, “you now find it in the far reaches of Africa… People see America as a real threat.”

Amongst our traditional allies, 85% of the French, and 70% of Germans, Spanish, Australians, South Koreans and Canadians feel that the U.S. does not take the interests of other countries into consideration.

That this qualifies as a new low for American diplomacy is hard to dispute. But another question remains: Does it really matter? Given the United States’ overwhelming military might, what difference do opinion polls make?

* * * * *

5.1

Global power is not premised on a taste test, nor, as Bush himself put it, a “focus group.” Some may feel content with the idea that, confronted with Machiavelli’s famous question concerning “whether it is better to be loved than feared or feared than loved,” our President simply opted for the latter.

There are reasons why this view is short-sighted, however.

At a minimum, most people recognize that global resentment threatens our safety. Looking at the world and asking, “Why do they hate us?” does little good if the next question is “Who cares what they think?” Alienating our allies preempts the type of cooperative police work needed to track down terrorists. And while our investments in tanks and missiles may intimidate rival states, they do little to quell fanaticism.

Yet this self-interested concern for our own security produces only the most limited, the most fearful reason for why the people of the United States should pay attention to world opinion. It should not be too much to hope that a regard for the views of others can grow from a sense of fellowship and solidarity, more than our fear of attack from abroad.

Aren’t we against terrorism everywhere? Isn’t the peace that we seek a global one? If the events of 9/11 do not inspire a sense of sympathy for those in the world who are regularly confronted with their vulnerability, than we have failed to absorb a vital lesson.

* * * * *

5.2

Maybe it is moralistic to hope for this type of solidarity. Maybe such sentiments have no place in diplomatic affairs. But this is not the point of contention in current U. S. foreign policy. The peculiar fact is that, on today’s world stage, everyone claims to stand in the interest of the world community, to act on behalf of the poor.

President Bush, it seems, wants to be loved.

The White House’s vision of the world is highly moralistic. Most fundamentally, it invokes the idea of freedom to justify its actions. In an op-ed written for the anniversary of September 11th, the President announced that “securing freedom’s triumph” is “America’s great mission.” Freedom is what separates us from the “evil-doers.” It demands that we “liberate” foreign nations.

There is no need to speculate about what this freedom will entail. A very particular view of the concept resides openly within the rhetoric. There is “a single sustainable model for national success,” announced the Bush Administration’s National Security Strategy. It requires “free enterprise” and “free trade” in “every corner of the world.”

“If you can make something that others value,” the White House says, “you should be able to sell it to them. If others make something that you value, you should be able to buy it. This is real freedom.”

Autonomy and self-determination appear to lie outside this “single model,” outside of “real freedom.” European peoples are not free to decide, as a precautionary measure, to instate a ban on genetically modified foods. Rather, the U.S. upholds the freedom of agribusiness to access foreign markets. (In this case, another of Bush’s moral arguments contends that Europe stands guilty of “hinder[ing] the great cause of ending hunger in Africa,” a cause that CEOs apparently hold dear.)

The type of freedom offered by military “liberation” can also prove circumscribed. The media watchdogs at Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting noted a March 19 slip by Tom Brokaw, in which the NBC anchor voiced a sentiment that lies only slightly beneath the surface of Washington’s neoconservative foreign policy: “We don’t want to destroy the infrastructure of Iraq,” he said, “because in a few days we’re gonna own that country.”

International public opinion puts the lie to our President’s do-good crusade. Those who make up the majority of the world say no. They tell the White House to stop doing them any favors. They assert that real freedom does not permit imperial ambition.

There is also a hopeful message, though; it suggests that perhaps they do not hate us after all. When asked to distinguish between the American people and the government, large majorities in France, Germany, Britain and Italy held a favorable view of the American people. Elsewhere, too—in Indonesia, Morocco, Pakistan, Nigeria—those who spoke negatively of our country referred to the government holding power in Washington, rather than its citizens.

Rejecting the “liberation” of pre-emptive strike and the “freedom” of corporate expansion should not mean shrinking into isolationism. Americans are inextricably linked to those who speak through opinion polls and international protest. Their distinction, between our people and our government, should guide a moral vision for the world.

* * * * *

Chapter 6

March 2004

As Bush proclaimed “Mission Accomplished” at the end of April 2003, a perception emerged that the peace movement was a failure because it was unable to stop the invasion. There is no doubt, however, that the visible, outspoken, and sometimes disruptive global protests significantly shaped public understanding of the war.

In the wake of the protests on February 15, 2003, The New York Times famously labeled “world public opinion” as the second of “two superpowers on the planet.” In several countries, most notably Spain (where the anti-war left just succeeded in ousting a pro-war government) forces standing in opposition to the invasion and occupation of Iraq have significantly altered the balance of power within their governments. It is possible that international outrage stopped the administration from fulfilling neoconservative desires to follow- up on the invasion of Iraq with assaults on Syria and Iran.

Due to strong expressions of dissent, the war in Iraq was framed as a fiercely disputed affair. The taint of controversy limited the surge of support that any U.S. president can expect to receive when commanding troops overseas, and set the stage for the later scandals that would plague the Bush administration. The relentless scrutiny and criticism by the peace movement of the faulty case for invasion would ultimately gain mainstream traction and leave the President flailing to defend his wartime lies and deceptions.

Movement critiques helped to discredit the popular myth of a link between Hussein and Al Qaeda, disrupting contentions that the Iraq war was an effective way to fight terrorism. Denunciations of the administration’s corporate pandering appeared especially trenchant following a series of no-bid contracts offered to well-connected U.S. businesses, as well as after persistent scandals about Halliburton profiteering. The administration’s misuse of police powers to target opponents of the war helped to feed a backlash of civil libertarians calling for the repeal of the Patriot Act.

In winter 2004, after search teams in Iraq failed to produce weapons of mass destruction, the central justification of the war collapsed and public support of the invasion weakened. In this context, critics of the war effort have found many of their arguments more readily accepted than ever.

* * * * *

6.1

Still, John Kerry’s “anti-war” position is barely passable—something he belatedly adopted after initially voting to authorize an invasion. For better or worse, the candidate keeps up “presidential” appearances by explicitly distancing himself from claims that a U.S. “empire” exists. He instead prefers to talk about Bush administration “mistakes” and errors of judgement. The peace movement may have good reason to support Kerry, but we would be foolish to expect him to voice our views of U.S. policy for us.

Concerning the immediate future, the main institutions of the U.S. peace movement have been well aware of the need to approach a coalition effort with an agenda of their own. The newspaper War Times, while celebrating Bush’s poor showing in the polls, argues for the need “to continue to push our peace demand ourselves—and push Democrats to follow.” Many activists would take from this a plan for “critical support” of John Kerry. Of course, when it comes to mainstream presidential candidates, the U.S. left has proven itself better at the “critical” part of things than at “support.” Along similar lines, United for Peace and Justice’s 12-month strategy paper speaks of “shaping the debate.” This is an admirable goal, but probably is too ambitious and diffuse to plan around effectively.

* * * * *

6.2

When the White House tries to portray its Iraq conquest as a victory for freedom and justice in the world, peace activists have a more specific job: to challenge the rosy story line, to expose the lies, and to highlight the true costs of neoconservatism. Already, we have made considerable strides in this direction, forcing the administration into what The New York Times describes as a “slow retreat… a day-by-day, fact-by-fact backing away from assertions they made with such confidence nine months ago.”

Writer Naomi Klein, among others, is now forcefully arguing that the privatization of Iraq’s economy will be a vital front in this effort. As each of the leading justifications for war—first the weapons of mass destruction, then the links with al Qaeda—has fallen away, Bush has increasingly been forced to fall back on humanitarian reasoning. His apologists now frame the war as an effort to promote democracy. It will be incumbent upon peace activists, drawing on a wider analysis of global injustices, to raise questions about what version of “freedom” the White House is actually offering.

After all, what kind of democracy is the Bush administration promoting when the occupying authority has already sold away the Iraqi economy—where virtually everything is newly privatized, where there are no limits on the controlling interests of foreign corporations, where profits are expatriated, and where pre-arranged Structural Adjustment programs put handcuffs on national policymakers? Freedom for a well-connected corps of multinational profiteers and true self-determination for the Iraqi people are two very distinct things. It’s the job of the peace movement to publicize the difference in a way that can resonate with a large portion of the American electorate.

* * * * *

Conclusion

May 6, 2004

From the start, the Bush administration’s response to the 9/11 attacks was phrased in militaristic terms. Rather than an international police action-—a manhunt for terrorists who perpetuate crimes against humanity—the White House launched a “war,” suggesting that our security would be based on military might.

That idea was flawed.

I drew this collection from essays published in the last two and a half years. Sadly, the war is not over, and it will not end soon.

In the past years we have witnessed the tragic failure of the neoconservative doctrine that “unquestioned U.S. military preeminence” should form the foundation of world order.

If we are to end a perpetual war, Americans must force the White House to understand that alternatives exist, and that real security will depend on pursuing them.

__________

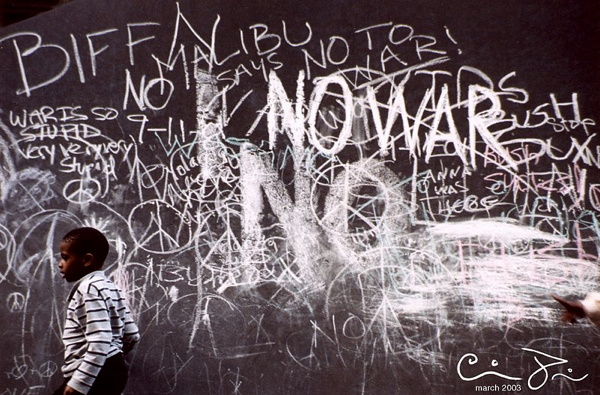

Top photo credit: Señor Codo, Graffiti in Daley Plaza, Chicago / Wikimedia Commons.