While spying on one’s allies may not be unusual at the UN, new charges against the US and Britain paint a damning picture of the unseemly push for war in Iraq.

Published on TomPaine.com.

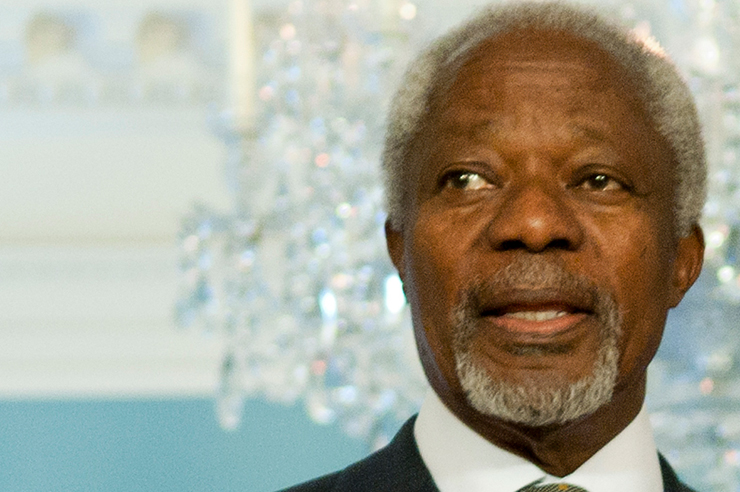

We now know, from disclosures in Britain and from senior officials at the United Nations, that US and British intelligence aggressively spied on UN diplomats—from Kofi Annan and Hans Blix to allies from Mexico and Chile—to prevent any delay of an invasion of Iraq. As more nefarious details of the spying have come to light, it has become increasingly clear why US news agencies that thus far have been uninterested in probing these revelations should take another look. The story raises important questions about whether the American public will have a chance to examine the full record of how our country was led to war.

For those who follow international diplomacy, it is no surprise to hear that spying takes place at the United Nations. But this fact should not obscure the bigger picture. In light of the President’s crumbling case for the urgency of war in Iraq, many Americans would no doubt be interested to learn about underhanded efforts to stop allies from crafting a compromise UN resolution that would have given more time for arms inspections to proceed.

Last Thursday, former British cabinet member Clare Short came forward with charges that her government had secretly recorded Secretary General Kofi Annan’s private conversations during the weeks of delicate negotiations before the invasion. On Saturday, UN arms inspector Hans Blix accused the proponents of war of spying on him as well, indicating that a Bush administration official had shown him photographs that only could have been taken by unscrupulous means.

These revelations are merely the latest pieces of bad news for President George Bush and Prime Minister Tony Blair, who face growing outrage about their treatment of allies like Mexico and Chile who disagreed with their militaristic stance on Iraq. Last March a whistle-blower from British intelligence leaked a memo to the London Observer showing that the Bush and Blair governments were secretly monitoring the six non-permanent members of the UN Security Council.

The memo belies White House claims that it viewed war as a last resort. In an important scoop, the Observer explains that the leak suggested “that despite the US agreeing to more time to find a resolution, it secretly used intelligence from spying on those negotiations to kill the last hope of a UN resolution” that might have prevented an invasion.

“At every step,” the newspaper’s reporting alleges, the intelligence operation “attempted to undermine the independent deliberations of the Security Council as it stood on the brink of war.”

The most revealing testimony comes from Former Mexican UN Ambassador Adolfo Aguilar Zinser, who says that, with the knowledge of independent negotiations obtained by spies, the US intervened to prevent a compromise resolution. “When they [the US] found out, they said you should know that we don’t like the idea and we don’t like you to promote it,” he said.

“We were looking for a compromise and they say, ‘Do not attempt it.'”

The White House has some explaining to do, and it should be pushed by reporters to do it. That’s why the American public is ill-served by news reports that shrug off the surveillance as a “long-standing” practice.

The New York Times, while running stories about how the UN spying scandal has exploded in Britain, has tended to downplay charges about espionage against Blix, Annan, and other allies. The paper’s editors have emphasized that “Spying on the conversations of even friendly diplomats has a long history, and those who follow intelligence issues will not be surprised by the latest allegations.” The Times contends that “The news here may be less the surveillance and more the willingness of a former cabinet official from Mr. Blair’s own party to reveal such sensitive intelligence information in public.”

This position misses a key point. Even if surveillance at the UN itself is not shocking, the reports about covert US and British activity reveal unseemly information about how these governments strong-armed allies in the push for war. Similarly, the idea that the White House might have viewed Hans Blix, whose inspections were proceeding all too successfully to support US militarism, as the enemy is certainly a noteworthy story. The British Independent writes, “The alleged bugging of Dr Blix… is being viewed in diplomatic circles as part of a concerted effort to sabotage attempts at a peaceful solution to the Iraq crisis.”

Even the Times acknowledges that “if Mr. Annan’s communications were intercepted, laws, as well as diplomatic crockery, may have been broken,” and that “[s]ubstantive harm may have been done as well” if Annan was not able to work effectively. US news agencies should be working to determine how illicitly obtained information about Annan and Blix was actually used, and what “substantive harm” resulted.

Moreover, it is clear that much of the world views the prewar UN spying with considerable disdain. In past weeks, the story has heated up in Mexico and Chile, whose government officials have lodged official protests. Under intense diplomatic pressure to cooperate with the US war effort, many foreign officials did not speak out when the memo was first revealed. But that reluctance has now disappeared. Current Mexican Ambassador to the UN Enrique Berruga characterizes the spying as “a serious break with a series of rules of the game in the world of multilateral diplomacy.”

In Britain, Blair tried to quiet the scandal by dropping the charges against the agent responsible for leaking news of the spying. Unfortunately for him, fresh allegations from Clare Short and Hans Blix surfaced within days, making it likely that the British public, at least, will have an opportunity to get a clear view of the ugly tactics used to push a the latest Gulf War.

The US media’s “ho-hum” response to the UN spying is perhaps not surprising, given that Americans seldom give much weight to international opinion. But President Bush’s success in offending the world community is no small matter. Any real pursuit of terrorist networks will require international cooperation and the responsible use of intelligence agencies. US actions against allies who opposed the Iraq war didn’t help that pursuit.

In the past months, as they have been subjected to increasing scrutiny, the major rationales used to justify the Iraq war have steadily eroded. Before the elections this fall, the tactics used to push the war effort on the international scene also deserve full examination. Reporters and elected officials should seize opportunities to shed light on prewar diplomatic maneuvering and to ask hard questions about the lasting impacts of Bush administration policy.

The lively public discussion that has emerged overseas suggests that the UN spying scandal is an excellent place to start.

__________

Research assistance for this article provided by Jason Rowe. Photo credit: U.S. Department of State.