The famous writer championed a proud tradition American anti-imperialism.

Published in Global Beat Syndicate.

It was autumn, electoral campaigns were in full swing, and U.S. intervention abroad represented a crucial issue separating the political candidates. Amidst the excitement, one of America’s foremost literary personalities made a homecoming that was both celebrated and politically charged.

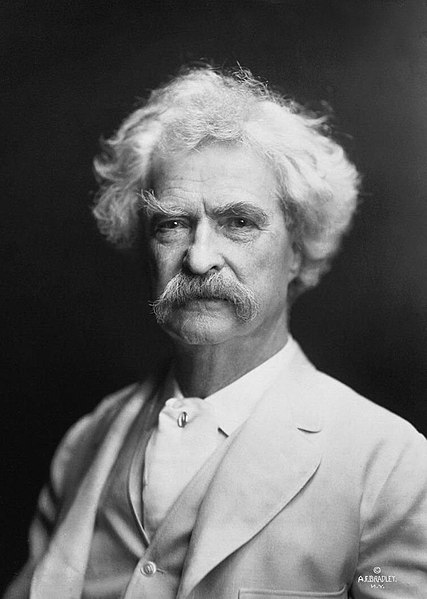

The writer was Mark Twain and the year was 1900. The nation was engaged in an intense debate over its military action in the Philippines, a country that it had recently bought for $20 million dollars at the conclusion of the Spanish-American War. Twain, who had been living abroad for nearly ten years, brought a prescient analysis of the situation.

Initially, he had supported the war. “I said to myself, here are a people who have suffered,” Twain explained, echoing the White House’s rationale for action. “We can make them as free as ourselves, give them a government and country of their own, put a miniature of the American constitution afloat… start a brand new republic to take its place among the free nations of the world.”

“But I have thought some more, since then,” he said. Upon reading the 1898 Treaty of Paris and questioning the official motives for war, Twain concluded: “We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem.”

“And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

By the turn of the century, Mark Twain, born Samuel Clemens, had already established his place amongst America’s most revered authors. He had never hesitated to weigh in about politics. (“Suppose you were an idiot and suppose you were a member of Congress,” he famously quipped. “But I repeat myself.”) As Twain Scholar Jim Zwick has documented, anti-imperialism became a cause to which the writer would make one of the most serious political commitments of his life.

Twain’s skepticism about US involvement in the Pacific grew throughout the first decade of the new century. President Theodore Roosevelt declared an official end to war in the Philippines on July 4, 1902, but the US would maintain controlling a military presence for decades, facing frequent skirmishes. As Twain had warned, “we have got into a mess, a quagmire from which each fresh step renders the difficulty of extrication immensely greater.”

The writer was offended that an ostensible fight for independence ended with a close American guard over Filipino assets, charging that “Uncle Sam paid that $20 million for his entrance fee into society — the Society of Sceptred Thieves.”

And when apologists for the White House, like General Frederick Funston, argued that anti-imperialist critics should be “hanged for treason,” Twain retorted that he was “quite willing to be called a traitor — quite willing to wear that honorable badge — and not willing to be affronted with the title of Patriot and classed with the Funstons when so help me God I have not done anything to deserve it.”

Needless to say, if Mark Twain were alive today, he would not be surprised to see that George W. Bush professes his admiration for “Theodore Rex,” nor that the President recently pointed to the Philippines as a model for Iraqi “liberation.”

While Bush declared “Mission Accomplished” with top gun bravado some six months ago, our military has only been drawn deeper into the occupation of Iraq. The official “Peace Toll” of US soldiers killed reached 100 in mid-October. And with the administration resisting European demands for timely elections, there is no exit in sight.

Few have been more enthusiastic about the US occupation than firms with close ties to the White House, such as Halliburton and Bechtel, which have received billions of dollars in well-publicized no-bid contracts.

Remarkably reminiscent, the administration has also cultivated a “with us or against us” culture that labels dissenters as unpatriotic, or worse. In one recent incident, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld suggested that criticism of the war in Iraq helps terrorists.

In challenging US militarism, Twain was not acting alone. He was backed by the Anti-Imperialist League, an organization that said that Roosevelt’s brand of expansionism violated the nation’s core beliefs in freedom and liberty. Today more than ever, we do well to honor the tradition of Americans who oppose the creation of empires — ours or anyone else’s.

And as for Iraq, we should remember Mark Twain’s sentiments regarding the people of the Philippines. “I thought it would be a great thing to give [them] a whole lot of freedom,” he said, “but I guess now that it’s better to let them give it to themselves.”

__________

Research assistance for this article provided by Jason Rowe. Photo credit: A.F. Bradley / Wikimedia Commons.