Bush Administration abuses perpetuate an atmosphere of intolerance against immigrants.

Published in Z Magazine.

The Justice Department was resolute: “We make no apologies,” officials said about their pursuit of homeland security. And while some might find this attitude from law enforcement authorities reassuring, the release of a critical report from the Department’s own inspector general was not an occasion where intransigence should make anyone feel safe.

In late May, an internal Department of Justice review confirmed what critics had long charged were frightening violations of civil liberties and due process in the wake of 9/11. The report showed that the 762 non-citizens who were rounded up after the attacks were put in cells where the lights were never turned off and kept in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day. They were cuffed and shackled in leg irons before they were moved. And guards slammed them against walls in advance of videotaping their statements.

The report showed that, when detainees went to contact their lawyers, guards gave them wrong numbers to dial, or interfered with their calls. And that authorities lied to those outside as well: When family members asked after a loved one at the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, New York, they were repeatedly told that the person was not being held at that facility.

In the end, none of those Muslim men who were held in the post-9/11 sweep was charged with crimes relating to terrorism. (Zacarias Moussaoui, the only individual with relevant charges pending, was in custody before the attacks.) Many were never even suspected of such crimes; although they did not learn of their charges for weeks on end, they were held only for minor immigration violations. The common denominators among them were race and religion.

Accusations of mistreatment at the hands of federal authorities are not new. Family members and community organizations have been working to publicize the plight of detainees since their initial arrests. Yet the internal report not only confirms the claims of these activists, it points to a wider trend: In the age of “homeland security” immigrant rights have come under an intensified assault. And government abuses are only feeding the atmosphere of intolerance.

Since most of the detainees have been deported or released, commentators overwhelmingly spoke about the contents of the inspector general’s report in past tense. Many, while critical, appeared to agree with Joseph Billy Jr., the FBI’s overseer of counter-terrorism in New York City, who pointed to special circumstances and cited “the tenor of the times after 9/11.”

But a flood of news items since the report’s release in late May show that the government’s actions do not reflect an anomalous period of abusiveness. They mark instead an official attitude that increasingly views immigrants as criminals, rather than a key source of strength and diversity for our country.

For its part, the Justice Department’s attitude of indignation mutes its vows to implement reforms based on the inspector general’s recommendations. As other observers have noted, the Administration has taken an unbalanced stance: Ashcroft’s lieutenants swear they have done nothing wrong—and that it will never happen again.

Meanwhile, the Department’s attorneys continue fighting in court to defend their practices. They have been distressingly successful in legitimating tactics that strike at core protections afforded by our legal system. On May 27, the Supreme Court rejected a challenge to secret deportation proceedings, which are closed to family members, the press, and the public.

Three weeks later, on June 17th, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the Justice Department practice of secret arrests—holding suspects in secret and refusing to release the names and locations of detainees. Dissenting Judge David S. Tatel called the decision an “uncritical deference to the government’s vague, poorly explained arguments” for withholding basic information about suspects’ conditions, an act that prevents watchdogs from determining whether the Bush Administration is violating the constitutional rights of those in custody.

The President assures us that he is not waging a war on Islam, and that he wants to work with local neighborhoods to locate the real terrorists. Yet he has treated huge numbers of Arab and South Asian non-citizens as suspects, fueling discrimination against immigrant communities. Since last November, the government has mandated that non-citizen men from 25 nations report for mass “special registrations.” Except North Korea, all are predominately Muslim countries. Among the 82,000 people who waited in long lines to voluntarily comply with the order to register—a contingent unlikely to include a lot of terrorists—hundreds were shackled and jailed for problems as trivial as falling a few credits short of the course-load requirements on a student visa.

Some 13,000 who registered were given orders to appear for court proceedings that could possibly result in expulsion from the country. Deportations and fear of discrimination has sparked an exodus of residents from neighborhoods like New York’s “Little Pakistan” on Coney Island Avenue, where storefronts and restaurants are emptied.

Didn’t the White House officially end racial profiling? On June 17, the Bush Administration announced with great fanfare prohibitions on the discriminatory policing practices that have attracted so much attention in the past decade. But, as the ACLU pointed out, the guidelines were released by the Justice Department’s civil rights division, the same office that “has come under increasing fire over the past year for dropping a number of ongoing cases against municipalities accused of police brutality and racially prejudicial law enforcement.” Moreover, the “ban” only perpetuates selective persecution committed in the name of national security. Top officials point to exceptions in the new rules for investigations involving “terrorists,” and assure us that programs like Special Registration will continue.

Muslims, Arabs, and South Asians are not the only ones under attack. In the third week of June, Amnesty International and Physicians for Human Rights each released reports decrying the treatment of asylum-seekers—those who come to our country to escape torture and oppression abroad. These investigations show that already poor conditions have only worsened in the past year. About one-third of all children in the custody of U.S. immigration authorities, although accused of no crime, are reportedly subjected to shackling, verbal abuse, solitary confinement, or exposure to the adult prisoner population.

Finally, on Arizona’s border with Mexico, a new wave of vigilantism has risen since 9/11. Increasingly large groups patrol the desert suited in camouflage, vowing to take homeland security into their own hands. Organizations like the Civil Homeland Defense militia have ties to white supremacists and are suspected by immigrant rights advocates of involvement in the murders of undocumented Mexicans, but have thus far escaped serious scrutiny from local authorities.

In response to these gangs, the White House has taken a frighteningly ambiguous position. Ari Fleisher responded to questions about the militias by saying, “The president believes that the laws of the land need to be observed and the laws need to be enforced.” As Max Blumenthal reported in Salon.com, this “might mean one of two things. Perhaps it was a warning that militia groups should stay within the law. Or perhaps it was an acknowledgment that federal agencies have failed at the border—and a careful way of cheering on the vigilantes.”

It would be nice to have a President who is above suspicion of supporting vigilantism. But we are not so fortunate today. In early March, when he was working to pressure Mexico to side with the U.S. in U.N. deliberations about the Iraq War, President Bush publicly worried—or threatened—that a “No” vote could lead to reprisals against some of the 28 million Mexicans living in the United States.

“I don’t expect there to be significant retribution from the government,” he noted in an interview with Copley News Service. But then he called attention to the “backlash against the French, not stirred up by anybody except the people,” and said that if Mexico opposed the U.S. “there will be a certain sense of discipline.”

As New York Times columnist Paul Krugman commented at the time, “These remarks went virtually unreported by the ever-protective U.S. media, but they created a political firestorm in Mexico. The White House has been frantically backpedaling, claiming that when Mr. Bush talked of ‘discipline’ he wasn’t making a threat. But in the context of the rest of the interview, it’s clear that he was.”

While White house spin doctors may claim that the President’s posturing falls short of a threat, George W. Bush’s apparent disregard for the safety of immigrants goes hand in hand with the abuses perpetuated by his Justice Department. And, ultimately, it’s hard to tell which is worse for the future of the country: that the climate of fear and discrimination nurtured in the age of homeland security is making life less safe for millions of people living in this country. Or that the Bush administration makes no apologies.

__________

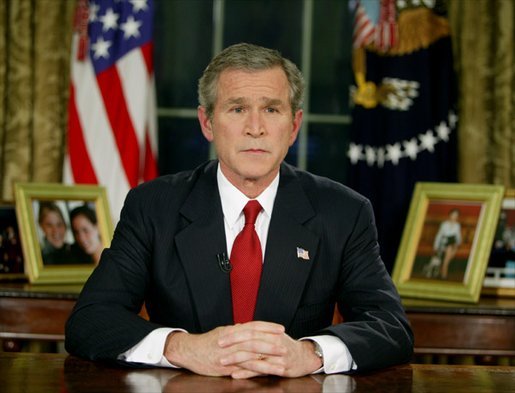

Research assistance for this article provided by Katie Griffiths. Photo credit: White House / Wikimedia Commons.