Does International Public Opinion Really Matter?

Published on AlterNet.

The news, simply put, is that the world hates us. Less than two years ago, following the attacks of 9/11, outpourings of sympathy for the United States flowed from around the globe. Yet those in power in Washington have swiftly converted that goodwill into distrust and contempt.

Poll results released by the Pew Research Center in the first week of June verified the fears that critics of President Bush’s military adventurism voiced all along. “Anti-Americanism has deepened, but it has also widened,” said Pew director Andrew Kohut. Not only has negative sentiment about our country intensified in places like Turkey, Indonesia, and the Middle East, “you now find it in the far reaches of Africa… People see America as a real threat.”

Amongst our traditional allies, 85% of the French, and 70% of Germans, Spanish, Australians, South Koreans and Canadians feel that the U.S. does not take the interests of other countries into consideration.

That this qualifies as a new low for American diplomacy is hard to dispute. But another question remains: Does it really matter? Given the United States’ overwhelming military might, what difference do opinion polls make?

Global power is not premised on a taste test, nor, as Bush himself put it, a “focus group.” Some may feel content with the idea that, confronted with Machiavelli’s famous question concerning “whether it is better to be loved than feared or feared than loved,” our President simply opted for the latter.

There are reasons why this view is short-sighted, however.

At a minimum, most people recognize that global resentment threatens our safety. Looking at the world and asking, “Why do they hate us?” does little good if the next question is “Who cares what they think?” Alienating our allies preempts the type of cooperative police work needed to track down terrorists. And while our investments in tanks and missiles may intimidate rival states, they do little to quell fanaticism.

Yet this self-interested concern for our own security produces only the most limited, the most fearful reason for why the people of the United States should pay attention to world opinion. It should not be too much to hope that a regard for the views of others can grow from a sense of fellowship and solidarity, more than our fear of attack from abroad.

Aren’t we against terrorism everywhere? Isn’t the peace that we seek a global one? If the events of 9/11 do not inspire a sense of sympathy for those in the world who are regularly confronted with their vulnerability, than we have failed to absorb a vital lesson.

Maybe it is moralistic to hope for this type of solidarity. Maybe such sentiments have no place in diplomatic affairs. But this is not the point of contention in current U. S. foreign policy. The peculiar fact is that, on today’s world stage, everyone claims to stand in the interest of the world community, to act on behalf of the poor.

President Bush, it seems, wants to be loved.

The White House’s vision of the world is highly moralistic. Most fundamentally, it invokes the idea of freedom to justify its actions. In a New York Times op-ed written for the anniversary of September 11th, the President announced that “securing freedom’s triumph” is “America’s great mission.” Freedom is what separates us from the “evil-doers.” It demands that we “liberate” foreign nations.

There is no need to speculate about what this freedom will entail. A very particular view of the concept resides openly within the rhetoric. There is “a single sustainable model for national success,” announced the Bush Administration’s National Security Strategy. It requires “free enterprise” and “free trade” in “every corner of the world.”

“If you can make something that others value,” the White House says, “you should be able to sell it to them. If others make something that you value, you should be able to buy it. This is real freedom.”

Autonomy and self-determination appear to lie outside this “single model,” outside of “real freedom.” European peoples are not free to decide, as a precautionary measure, to instate a ban on genetically modified foods. Rather, the U.S. upholds the freedom of agribusiness to access foreign markets. (In this case, another of Bush’s moral arguments contends that Europe stands guilty of “hinder[ing] the great cause of ending hunger in Africa,” a cause that CEOs apparently hold dear.)

The type of freedom offered by military “liberation” can also prove circumscribed. The media watchdogs at Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting noted a March 19 slip by Tom Brokaw, in which the NBC anchor voiced a sentiment that lies only slightly beneath the surface of Washington’s neoconservative foreign policy: “We don’t want to destroy the infrastructure of Iraq,” he said, “because in a few days we’re gonna own that country.”

International public opinion puts the lie to our President’s do-good crusade. Those who make up the majority of the world say no. They tell the White House to stop doing them any favors. They assert that real freedom does not permit imperial ambition.

There is also a hopeful message, though; it suggests that perhaps they do not hate us after all. When asked to distinguish between the American people and the government, large majorities in France, Germany, Britain and Italy held a favorable view of the American people. Elsewhere, too—in Indonesia, Morocco, Pakistan, Nigeria—those who spoke negatively of our country referred to the government holding power in Washington, rather than its citizens.

Rejecting the “liberation” of pre-emptive strike and the “freedom” of corporate expansion should not mean shrinking into isolationism. Americans are inextricably linked to those who speak through opinion polls and international protest. Their distinction, between our people and our government, should guide a moral vision for the world.

__________

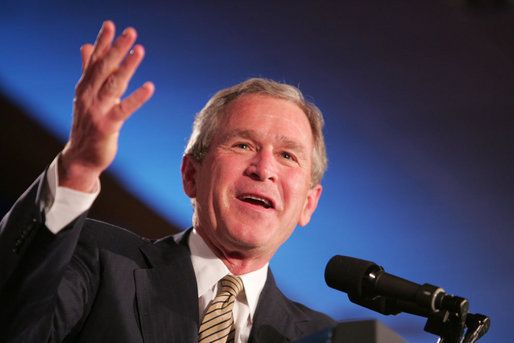

Research assistance for this article provided by Katie Griffiths. Photo credit: U.S. Federal Government / Wikipedia Commons