With Congress seemingly locked into war, democracy demands dissent. The protest in New York delivered.

Published on ZNet.

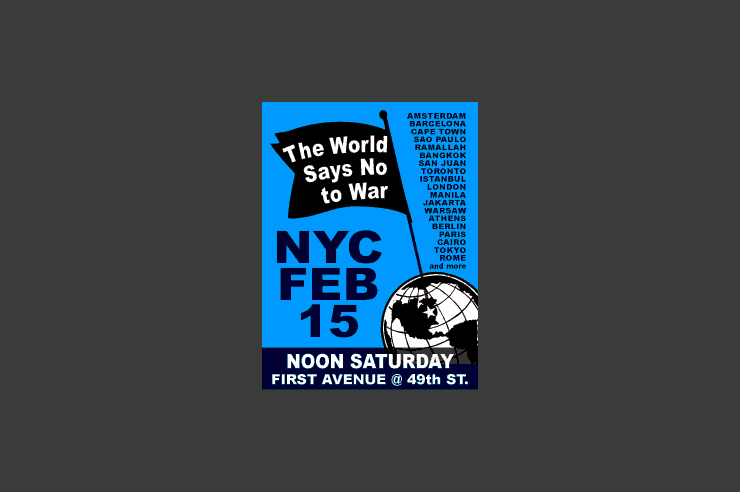

Starting from within view of the United Nations’ headquarters, a wall of faces stretched some twenty blocks up Manhattan’s First Avenue on Saturday. The antiwar rally then widened to cover over large sections of Second and Third Avenues as well. Whether the crowd size was closer to the pessimistic 100,000 estimated by authorities or the 400,000 claimed by organizers, two facts hold true: The demonstrators’ presence in New York was massive, and still it made up only a fraction of the weekend’s global mobilization against an invasion of Iraq.

The Los Angeles Times reports that at least a million people showed up for the largest ever march in London, two million rallied in Spain, 500,000 in Berlin, and 200,000 in Damascus, Syria. Another couple million demonstrated in Rome, and over 150,000 turned out in Melbourne, Australia, according to the Associated Press. Reuters says that more than six million people in over 350 cities across the globe joined in protests.

Indian writer Arundhati Roy helped to articulate the source of this widespread outrage. “The Bush Administration has launched a two-pronged attack,” she said in a telephone call broadcast through the streets of New York. In addition to its military maneuvers in the Middle East, Roy argued, the White House has commenced a separate attack “on the intelligence of the human race.”

It amazes me how thin a veil President Bush has kept over his plan for “regime change.” Of course, the presentations given at the UN by Secretary of State Colin Powell speak of disarmament rather than the selection of new leadership in Baghdad. But the idea is hardly hidden. The White House suggests elaborate plans for the post-war governance of Iraq. And it has given the headhunt for Saddam Hussein, a brutal but petty thug, an importance that overrides concern for our economy, the need for international cooperation, and even the capture of Osama bin Laden.

In the context of global protest, those who demonstrated in New York, as well as some 200,000 who gathered in San Francisco on Sunday, committed a uniquely pro-American act. They said that we, too, are appalled. They distinguished the fundamental decency of the American people from the renegade regime now in Washington. They refused to accept assassination as a national virtue. And they asserted that the way to overthrow tyrants is through movements for free speech, democracy, and human rights.

Few protest signs were as succinct and as significant in this respect as one held by a woman in front the Dixieland band that animated a carnivalesque procession of Bread and Puppet activists from Vermont. Her sign said simply: “Americans Against War.”

The “Code Orange” terror alert also created uncertainty in the city as the weekend neared. Friday night in the subways, I was surprised to find soldiers in full fatigues carrying machine guns. It is something I grew accustomed to when living in Central America, but never expected to see on my trip home to Brooklyn. I wondered if the rally would be similarly militarized.

The next morning, however, the soldiers were gone. Saturday at 10:30AM is not normally a peak hour for the trains, yet I stepped onto a subway car filled with people wearing buttons and carrying signs. Rally planners could foretell with relative accuracy how many busloads were coming in from out of town. But it was the unpredictable local turnout that would ultimately determine the size of the event. “New Yorkers are the ‘x’ factor,” one United for Peace and Justice organizer said to me earlier in the week. The packed subways eliminated doubt that the city had responded.

Having been denied the right to assemble and process in an orderly fashion, the attempts of various groups to get to the rally site themselves became marches. “Feeder” protests snaked through Manhattan’s streets, deploying from all corners. Puppeteers gained momentum walking alongside Central Park, teachers set out from St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and the “Militant Mothers Bloc” gathered between the two stone lions that guard the New York Public Library. There was a march for everyone, from the Interfaith Ministers for Peace to students down from New Haven, who yelled, “Bush’s war is going to fail, kind of like he did at Yale.”

The police bid to deny official space for these processions produced a traffic nightmare. On many streets, cars stood still for hours as marchers swarmed around. Next to one vehicle, still running its engine, activists chanted, “Hey, Hey. Ho, Ho. SUVs have got to go.” Apparently oblivious to how such a vehicle might have been treated in a European demonstration (one car was reportedly overturned in the Athens protests on Saturday), the driver shot perturbed glares at those who wrote anti-war slogans in the dust on his hood.

Signaling the movement’s broadening mainstream appeal, organized labor served as one of the most important constituencies in the rally. Unions ranging from the City University’s Professional Staff Congress to the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) sent sizable delegations. The healthcare workers union, 1199, went so far as to provide United for Peace and Justice with an office in its 42nd street building. Its politically powerful President, Dennis Rivera, addressed the rally as a featured speaker.

A key message coming from local labor representatives, as well as the national Labor Against the War coalition that New Yorkers helped form, was conveyed by a sign reading, “We Can’t Afford to Rule the World.” Many argued that at a cost that may run over $100 billion, this “preemptive” war in fact undermines the economic security of working people in this country.

Diverting attention from the recession and maintaining a focus on foreign affairs has thus far served the White House well. Some critics have suggested that the Bush Administration’s decision to announce a high terror alert for only the second time since the 9/11 attacks may have been politically motivated. “I think the high terrorist alert is part and parcel of gearing up for war,” said Bill Dyson, a State Representative from Connecticut, as he joined the New York rally. “They’re trying to scare the hell out of everyone and create hysteria.”

I have argued a different position. We have little reason to doubt that many dangers are real, because the Bush Administration’s unilateralist adventures abroad have succeeded in creating a more perilous world.

In either case, we face a dystopian situation: Those in power are able to thrive off of “combating” the same dangers that they busily cultivate. It is a state of perpetual war.

For New Yorkers, the added insult is that much of this is done in our name. My indignation about the exploitation of the city’s grief as a justification for war was rekindled when Angela Davis spoke from the rally’s podium. Davis contrasted the “march of fear”—a stream of people rushing to the hardware store to buy duct tape and plastic sheeting—with the “march of courage” taking place in cities throughout the world.

This rhetoric appealed to me because it mirrored two different types of patriotism that emerged after 9/11. Following the attacks on the World Trade Center, people in New York came together to honor the heroic acts of public safety workers, to assert our commitment to democracy, and to affirm the strength of our communities. Those residents who came out of their apartments to flood Midtown on Saturday recalled the distinctive sense of national community that swelled in the city almost a year and a half ago. Such feelings contrasted sharply with the statements of nationalism coming from Washington, DC. Those were phrased in fundamentalist tones, and claimed our grief as a call for vengeance.

The warlike sentiment may have dominated of late, ruling over a smirking State of the Union. But this weekend, New York City prevailed.

The response in Congress to the American people’s skepticism about invasion bears much in common with the paternalism of those high school authorities. “There is no debate, no discussion, no attempt to lay out for the nation the pros and cons of this particular war… This chamber is hauntingly silent,” said Robert Byrd (D-WV) in a recent speech before the Senate.

This may begin to change. Congressman Dennis Kucinich (D-OH), who took the stage in New York, is positioning himself as a leading anti-war representative, and he will soon announce his candidacy for President. Nevertheless, at the present moment Congress seems locked into war, and it appears that little will stop President Bush from having his invasion.

It is in these times when protest seems the most futile that it is perhaps the most important. An Associated Press story released Saturday reads, “Rattled by an outpouring of anti-war sentiment, the United States and Britain began reworking a draft resolution… Diplomats, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the final product may be a softer text that does not explicitly call for war.”

A “softer text” was not the demand of concerned individuals who demonstrated this weekend. Yet such a document provides an unusually sudden acknowledgement of the ability of protest to influence those in power. And it carries a reminder of a vital tradition in democratic political life: When the official avenues of discussion have been closed, democracy demands dissent.

That’s what the streets of New York, and the protests of millions worldwide, delivered.