Florida sugar growers milk taxpayers, farm workers, and endangered wetlands.

Cattails love sugar almost as much as people do. The stalky, marshland plants huddle in dense bunches on uncultivated areas bordering South Florida’s sugar farms. And the bunches are expanding ever southward into the wetlands. Technically, it’s not the sweet crop itself that they adore, but the phosphorus-laden fertilizers that run off the fields. Thriving on the chemicals, cattails suck oxygen from the swamp and crowd out native plants, destroying the established biological order.

In Florida, the swamp that they are destroying is known as the Everglades.

It is impossible to understand the fate of this world-renowned ecosystem without knowing the history of companies like U.S. Sugar and Florida Crystals. Florida growers took the lead in domestic sugar production through a combination of public subsidy and private malfeasance. They heaped dual abuse on migrant farm workers and Everglades wetlands. They have relied on handouts and trade protections, passed down for decades by politicians who are otherwise wont to praise the rectitude of “free markets.” And they have so effectively converted a fraction of their wealth back into political contributions that proponents of reform in Washington, D.C., are scarcer than impartial vote recounts in Palm Beach County.

Today, an expanded environmentalist campaign struggles to save the endangered Everglades. But fresh defeats handed to them this summer by Florida Governor Jeb Bush show that their adversary, Big Sugar, is as potent as ever.

* * * * *

For decades, the hand-cut harvest of sugar cane in Florida persisted among the United States’ greatest domestic disgraces. Until the U.S. Sugar Corporation was indicted in 1942 for violating Constitutional prohibitions against slavery, the then-infant industry lured African-American workers in southern states with promises of free transportation and payment of six dollars a day. A typical recruit told an interviewer that when he arrived, he learned that he owed eight dollars for the ride, plus another ninety cents for his cane knife and sharpener, plus room and board. He also learned that he would receive $1.80 for a day of labor. Many who tried to escape were apprehended by gun-wielding overseers, who happened to be deputized sheriffs for the county.

With too few U.S. citizens willing to endure such treatment, programs to bring seasonal workers from places like Jamaica, Barbados, and Haiti began in the 1940s and expanded vastly in the wake of the Cuban Revolution, when the embargo of a foreign competitor allowed Florida sugar production to expand ten-fold. Growers paid the migrant workers a brutal piece rate, demanding that one ton of sugar be cut per hour. Those who complained vocally or organized to go on strike—as 300 did in 1982 at Atlantic Sugar Growers—swiftly found themselves in Miami’s international airport, awaiting deportation.

In his 1989 book, Big Sugar, author Alec Wilkinson writes of a public relations film screened in the 1980s by the Florida Sugar Cane League. Discussing the cane cutters, the film’s narrator describes the workers’ plight as an ancient vocation. “To watch a West Indian wield a cane knife,” the voice says, “is to see a centuries-old art.” In fact, Wilkinson explains, the statement—something akin to celebrating African-Americans’ historic love of picking cotton—was flatly untrue. “Very few West Indian men… ever held a cane knife before arriving in Florida.”

“You mash your back from the never-ending turning and bending,” a Jamaican migrant told Wilkinson. “Your hand become like part of a machine; look at my palm; the [cane knife] rest here; it make a channel for its shape. When you go home, that one hand you have been cutting with you can’t use. It’s no good for anything else; you got to use the other one until it heal.” He concluded: “Our lives one day shorter for each day we cut cane.”

In the mid-1990s, workers who for years had been paid less than the legal minimum wage joined class action lawsuits to sue the cane growers, sometimes successfully, for millions of dollars in back wages. The victory, however, prompted more industrial maneuvering than lasting justice. For the 1997 season, the U.S. Sugar Corporation switched to 100 percent mechanical harvesting.

By then, the battleground for critics had definitively shifted: to the environment. Although the exploitative “guest worker” program became a thing of sugar’s past, the industry faced a high tide of public awareness about its role in permanently crippling the once-pristine Everglades.

* * * * *

Before developers set out to drain, channel, and control the famous wetlands, the bio-region consisted of a unique 6,000-year-old “river of grass” that stretched 100 miles from Lake Okeechobee to the Florida Bay. That Everglades has been all but lost to the demands of a growing population and an emergent sugar industry. By 1920, state and private interests carved four massive canals to divert water directly into the Atlantic Ocean, creating dry farmland. After the federal Army Corps of Engineers took over the “reclamation” in the 1940s, they built a complicated systems of levees and established a hydraulic system that bore little resemblance to the wet, flooded summers, and trickling winters that once defined the life of the Everglades.

The area now preserved as Everglades National Park is in fact only a dying remnant of the complete ecosystem. To its north is a large swath of land divided into Water Conservation Areas, which keep coastal residents of Miami, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach supplied with drinking water and protected from natural flooding. (The narrow strip of coastal South Florida now holds 5 million residents.)

Further North, the land closest to Lake Okeechobee is now known as the Everglades Agricultural Area. It is a massive farm, containing 700,000 acres used in the production of sugar cane. Sugar is a dry-land crop that must be constantly irrigated and never flooded if it is to survive. The fickle water requirements of the farms have gone far in dictating the hydraulic conditions for the rest of the Everglades—often leaving the National Park parched.

The industry’s other main impact on the environment comes from the spread of phosphorus and nitrogen fertilizers. While developers had imagined that the mucky soil pulled from the swamp would be fantastically fertile, sugar growers in fact have needed to spread tons of chemicals over their crops. Run-off from their fields has dramatically altered the chemical balance of the low-nutrient Everglades. Scientists indicate that the ecosystem would naturally contain phosphorus at a level of 5 to 7 parts per billion (ppb). Even a change of a few ppb can make a detectable difference and cost millions of dollars to eliminate through filtration. In past decades, swamplands catching runoff from the sugar farms contained levels of phosphorus measuring between 200 and 500 ppb.

In a November 1999 essay in Harper’s magazine, writer Paul Roberts explains that, “as concentrations rise even slightly, native plants, such as saw grass, react—first by growing to monstrously unnatural sizes, then by dying off and giving way to phosphorus-loving species, such as cattails.” The dense cattails prevent wading birds from landing, and kill off the algae that feeds Everglades fish.

It is uncertain whether the damage from the industry’s chemicals, and from the sugar-friendly water-management regime, will prove irreparable. But it is clear that these two developments must be reversed for the Everglades to recover. If and when that will happen is a question of politics.

* * * * *

Prosecutor Ken Starr’s report detailing the sexual misadventures of President Bill Clinton provides some interesting glimpses into how political power works in America. During one meeting between Clinton and Monica Lewinsky, the report explains, the couple was interrupted by a phone call from an irate campaign donor. Lewinsky remembered the name as “Fanuli.” In fact, it was Alfonso Fanjul, a South Florida sugar baron. Clinton promptly returned the call.

Over the years, the Fanjul family has grown accustomed to such high levels of political servicing. As owners of the Florida Crystals Corporation, Cuban-born Alfonso “Alfie” Fanjul, Jr. and his brother Jose, or “Pepe,” have the largest sugar cane holdings in the country. Their personal fortune is estimated conservatively at $500 million. Between 1990 and 2003, the sugar industry, led by the Fanjul brothers, sent $19.3 million in political contributions to Washington, according to the Center For Responsive Politics. Growers spent tens of millions more on local elections, especially in Florida. For the Fanjuls, the American two-party political system entails a simple division of labor: Alfie is a Democrat, Pepe a Republican. Leaders from each party eagerly seek the Fanjuls’ assistance as “Pioneer” class donors and campaign committee chairmen.

Historically, Big Sugar’s political clout has been needed to keep intact massive federal protections for the industry, which cost consumers an estimated $1.4 billion per year. In recent times, government supports and trade protections maintained a price of 18 cents per pound for domestic sugar, twice the global market rate. “Some people win the lottery; other people grow sugar,” writes libertarian James Bovard.

Increasingly in the past decade, growers have also used their political access to thwart Everglades restoration. In 1998, at the same time cane cutters were pursuing the lawsuits that would result in the mechanization of the sugar harvest, environmentalists also took legal action. That year, the U.S. Attorney in Miami sued Florida for failure to enforce clean water regulations. Big Sugar held up the challenge in court for years. Furthermore, growers began lobbying aggressively to control the legislative settlement that would ultimately emerge from the battle.

They won. Under the 1994 Everglades Forever Act the federal government and the taxpayers of Florida will ultimately put out $8 billion to clean up the wetlands, while polluters will pay a pittance. The law caps sugar industry payments towards water filtration systems at $320 million. As the Environmental News Network reported, the elder conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas, then 103 years old, demanded that her name be removed from the title of the legislation, which she considered a betrayal.

Subsequently, growers succeeded in defeating a variety of proposals to have polluters pay more. Alfie’s 1996 call to President Clinton happened only hours after Al Gore had publicly promoted a “penny tax” on sugar to fund restoration efforts. Because of Florida’s importance in U.S. presidential politics, it’s hardly surprising that the tax died a quick and quiet death.

In the most recent chapter of the dispute, Florida Governor Jeb Bush signed a state law in May that pushes back the deadline for reducing pollution levels to 2016. Under the new law, the state will wait 13 years before fully enforcing a 10 ppb phosphorus standard that was established in the late 1990s. The Palm Beach Post described the bill as “of, by, and for the sugar growers.”

Although federal officials threatened that Florida could lose national funding because of its unwillingness to uphold environmental standards, Big Sugar has not checked its political bravado. This summer, Florida Crystals and U.S. Sugar filed lawsuits demanding the removal of District Court Judge William Hoeveler, who originally mandated the tough phosphorus standards and who criticized Florida’s governor for signing the new legislation. Many on the American Right look forward to the day when George W.’s younger brother might become the third member of the Bush Dynasty to move into the White House. No doubt, if Jeb ascends, Big Sugar would be close behind him.

* * * * *

Their political influence has earned the Florida growers a place of infamy in American popular culture. The Washington Post notes that on The Simpsons, “Marge led a campaign against the villainous Mother-Loving Sugar Corp.” Fictional White House staffers on The West Wing demanded that Everglades money come “from the same place the pollution does—the sugar industry!” And it’s not hard to imagine on whom the evil sugar barons in the Hollywood movie Strip Tease, Joaquin and Wilberto Rojo, might be based.

In this context, the industry complains that it is a scapegoat. Growers point to the fact that their phosphorus pollution has decreased by 56 percent in the past decade. And they claim that other factors—like surging population growth and its attendant development—have even worse environmental impacts in South Florida.

It is true that America’s appetite for strip malls, golf courses, and superhighways may ultimately be as destructive as its taste for sugar. However, the improvements that have taken place in the sugar industry are the product not of growers’ benevolence, but rather public pressure. Today, corporate officials tout their “well-paid” workforce as reason to keep government subsidies, never mentioning how they fought determinedly into the new century to prevent migrant cane workers from winning their back wages in court. Similarly, the industry’s newly green press releases conveniently leave out its stalwart opposition to strong restoration measures.

Real environmental protection will come only with more public scrutiny of Big Sugar, not less. Until this pressure comes, political contributions will continue flowing north from Florida. And, in the Everglades, the cattails will continue sprawling south.

__________

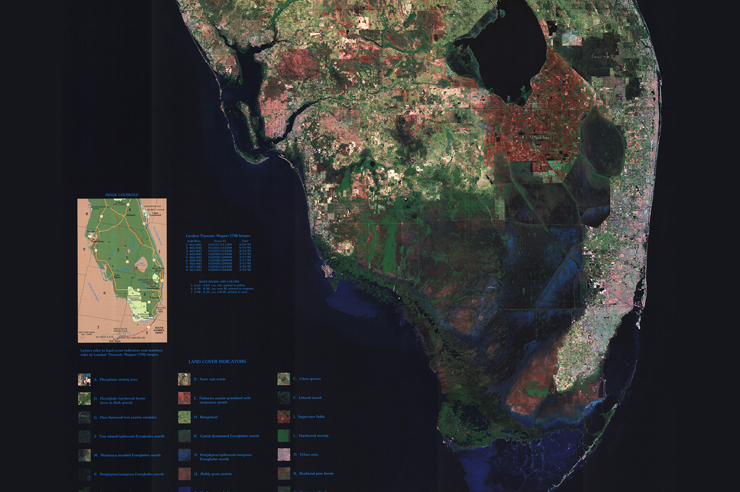

Photo credit: U.S Geological Survey / Wikimedia Commons.