On the surface, it would seem that getting lost requires little instruction, and that few of us would want to improve whatever talent for it we might possess. But in her new book, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit offers a compelling case for a state more commonly avoided than aspired to. Early on she quotes theorist Walter Benjamin: “Not to find one’s way in a city may well be uninteresting and banal. It requires ignorance—nothing more. But to lose oneself in a city—as one loses oneself in a forest—that calls for quite a different schooling.”

With a series of loosely intertwined personal essays, Field Guide aims both to help give us the necessary education in existential abandon and to explain the merits of this state of mind. Solnit writes, “To lose yourself: a voluptuous surrender, lost in your arms, lost to the world, utterly immersed in what is present so that its surroundings fade away. In Benjamin’s terms, to be lost is to be fully present, and to be fully present is to be capable of being in uncertainty and mystery.”

Solnit’s concern with consciousness and identity opens a broad terrain. A writer could go in many different directions in describing the processes of losing the self and then finding it again. That’s precisely what Solnit does. Her style is tangential, associative. She jumps from analyzing the movie Vertigo and its love affair with the San Francisco Bay Area, where she lives, to discussing a love affair of her own in the Mojave desert, to recounting the story of the Spanish conquistador Cabeza de Vaca. This explorer, after being hopelessly lost in the American interior, spent years wandering in search of his countrymen, only to discover, once he found them, that he had more in common with the native peoples he had come to admire than with their colonizers.

Solnit is idiosyncratic and learned. Of her young adulthood, she writes, “Punk rock had burst into my life with the force of revelation, though I cannot now call the revelation much more than a tempo and an insurrectionary intensity that matched the explosive pressure in my psyche,” and then she unexpectedly draws into her punk world Keats, Nabokov, Borges and the Road Warrior. You can only guess whether she will next plumb meaning from a friend’s off-handed remark or a passage out of Thoreau.

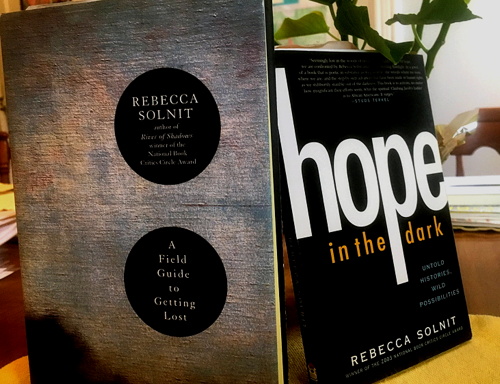

Amid her free-form meandering, you quickly detect a sense of control. The guiding intelligence of Solnit’s personal essays recalls Annie Dillard, while her naturalist’s affection for the Southwestern desert and the Great Salt Lake are reminiscent of Terry Tempest Williams. Then again, Solnit herself is no neophyte. Prior to Field Guide, she published eight books, including Savage Dreams, a work rooted in her anti-nuclear activism at the Nevada Test Site, and River of Shadows, a book about photographer Eadweard Muybridge that won the Nation Book Critics Circle Award.

Solnit’s profile as a political writer has risen considerably over the past couple years, in part due to Tom Engelhardt, whose TomDispatch.com distributes not only his own essays focusing on the U.S. occupation of Iraq, but also work by authors he has befriended, Solnit prominent among them. Out of her essays for TomDispatch came her eighth book, Hope in the Dark, a primer on activism in foreboding times.

“I’m concerned she can get away with saying things that aren’t true because they’re pretty,” a friend said to me of that earlier book. This seems like a genuine risk. Those of us who have grown weary of less-than-critical celebrations of “Internet organizing” and the revolutionary power of anarchist-inspired Temporary Autonomous Zones will find a few sources of complaint in Solnit’s treatise on hope. Yet there are many more things in that slim volume that are as truthful as they are poetic: “Causes and effects assume history marches forward,” she writes, “but history is not an army. It is a crab scuttling sideways, a drip of soft water wearing away a stone, an earthquake breaking centuries of tension.”

With her new Field Guide, Solnit earns our confidence with the strength of her personal reflections and cultural insights. She tells us that our word “lost” comes from the Old Norse los, “meaning the disbanding of an army, and this origin suggests soldiers falling out of formation to go home, a truce with the wide world.” She adds: “I worry now that many people never disband their armies, never go beyond what they know.” It is, no doubt, a warranted fear. And it should make us hope that Solnit finds many pupils for her tutelage in the unknown, which proves both beautiful and true.