Honoring Baker alongside Martin Luther King would highlight the long and patient work of building a social movement.

Published in The Nation.

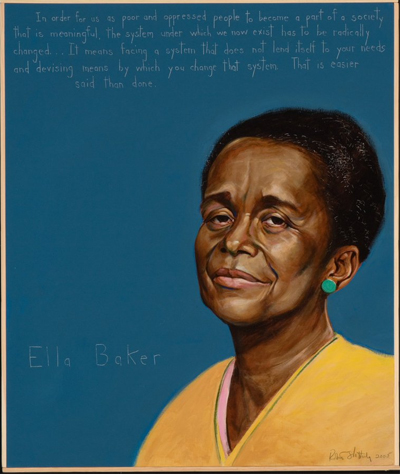

Around the country, a new holiday has started to appear: Ella Baker Day.

From North Carolina to Virginia to Maryland to New York, groups have organized events and lobbied local governments for a commemoration of a woman who was almost universally revered within the civil rights movement, but is less familiar to most Americans today. While these groups have often chosen a day in April for their celebrations, others have suggested that on the long weekend of the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday, Baker should be recognized alongside King.

King was undeniably an inspirational leader who deserves to be honored. But this weekend also should allow us to appreciate other contributors to the civil rights movement. The life of Ella Baker highlights a different model of leadership and gives insight into the long and patient work of building a social movement. While King is justly remembered as a powerful preacher and rousing orator, a political strategist and practitioner of nonviolent direct action, Baker calls attention to a more specific role: that of the organizer.

Drawing from activist Bob Moses, the sociologist Charles Payne has argued that the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s actually contained two distinct traditions. One he labels “the community-mobilizing tradition,” which was “focused on large-scale, relatively short-term public events.” Payne sees this lineage as “best symbolized by the work of Martin Luther King,” and he includes in it such well-remembered events as the March on Washington and the famous campaigns in Birmingham and Selma, Alabama. The second is a tradition of community organizing. This is a lineage, Payne writes, “with a different sense of what freedom means and therefore a greater emphasis on the long-term development of leadership in ordinary men and women,” and it is a tradition best epitomized “by the teaching and example of Ella Baker[.]”

Ultimately, both dramatic mass protest and long-term organizing were essential to the historic gains of the civil rights movement. But in retellings of what it took to secure change, the latter work is too often forgotten.

Baker herself had a diverse set of talents and a commitment to social justice that was rooted in her earliest experiences. Born in 1903 and raised in Virginia and North Carolina, she grew up hearing the stories of her maternal grandmother, a former slave who had been whipped for refusing to marry the man chosen for her by the plantation owners. A sharp debater and accomplished public speaker from a young age, Baker graduated as valedictorian of her class at Shaw University in 1927. Moving to upper Manhattan during the height of the Harlem Renaissance, she immersed herself in community affairs and served on the mastheads of two local newspapers.

Although she had long embraced the role informally, Baker officially assumed a position as an organizer when she served for much of the 1940s as a field secretary for the NAACP. She was eventually promoted to national director of branches. The work involved constant travel as she formed new organizational chapters and revived dormant ones. Congressman John Lewis, himself a towering civil rights figure, writes that Baker “single-handedly organized dozens of youth chapters of the NAACP throughout the South.” But “single-handed” does not aptly describe how Baker thought of her craft.

Her organizing was about building relationships—about forming deep ties with people who had not necessarily considered themselves part of a political movement before. She instilled in people a belief in their self-worth and ability to lead, and she cultivated their capacities for independent action. This is what Baker called the “spadework” of movement-building, less glamorous than giving a speech to a crowd of thousands or participating in headline-grabbing protests, but just as critical to generating social change, if not more so.

As Barbara Ransby, author of the biography Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, writes, Baker promoted “an inclusive style of democratic leadership” that valued local knowledge. “She had learned from her work with the NAACP, both in the South and in Harlem, that any viable social change organization had to be built from the bottom up. ‘Authentic’ leadership could not come from outside or above; rather, the people who were most oppressed had to take direct action to change their circumstances.” Pursuing this philosophy, Baker sowed countless seeds. Among those local leaders who attended her training conferences in the 1940s, for example, was a Montgomery, Alabama activist named Rosa Parks.

Baker also played a prominent role in King’s Southern Christian Leadership Council. Formed in the late 1950s, in the wake of the successful Montgomery bus boycott, the SCLC had been conceived as an organization that could carry forward the momentum of the campaign and serve as the political arm of the black church in the South. In her three years with the group, Baker would serve as its acting executive director, helping to shape its early voter registration programs and its backing of local civil rights campaigns.

Yet she chafed against the SCLC’s organizational culture, which gave a board of all-male preachers authority and relegated women to support roles. Baker rejected the imposed standards of conventional femininity: At a time when women were expected to be quiet and deferential, she was opinionated and outspoken. She elevated the work that women undertook, often far from the limelight, to sustain local struggles. She protested poor treatment of the female clerical staff at the NAACP, SCLC, and beyond. And she declined to publicly discuss her marital status—or to have her place defined by it.

As Lewis wrote in his memoir Walking with the Wind, “Long before people began using the term ‘male chauvinism,’ Ella Baker was describing it and denouncing it in the civil rights movement, and she was right. There were very, very few women getting credit for their work, and even fewer emerged into leadership positions.” Ransby quotes an interviewer who, after listening to Baker, remarked that the SCLC ministers seemed to “respect your abilities on the one hand, and fear your independence on the other.”

Baker was also concerned with what she saw as an overreliance on charismatic leadership. High-profile figureheads could be made and unmade by the media, she warned. Moreover, the belief that action must be initiated by a famous name risked disempowering the unheralded participants who make up the backbone of any movement. “In Baker’s view,” Ransby explains, “oppressed people did not need a messiah to deliver them from oppression; all they needed was themselves, one another, and the will to persevere.” Or as Baker put it herself in 1973, “People have to be made to understand that they cannot look for salvation anywhere but to themselves.”

The shape of Baker’s career reflected such beliefs. Although she was often a featured speaker, she put a greater emphasis on listening—especially to people who were rarely heard. Against the norms of many civil rights groups, she looked for organic leadership outside of the ranks of the credentialed middle class, and sought out those who were reluctant to nominate themselves.

Baker lived to the age of 83, and, into the 1980s, she was as politically engaged as her health would permit. Rather than a few moments in the spotlight, her legacy was defined by more than five decades of steady contributions to social movements. But if there was a key moment that illustrates the pivotal consequences of her decisions, it came in April 1960.

In the preceding months, young African American students had begun placing orders at segregated lunch counters and refusing to leave when they were denied service, creating a crisis for the Jim Crow order. The tactic quickly spread. Soon the sit-ins were producing hundreds of arrests, drawing national attention, and sometimes sparking enraged responses from racist onlookers. Baker recognized the importance of absorbing and expanding the energy generated by this wave of civil disobedience. Although she had been ready to resign her post at the SCLC, she convinced the group to sponsor an event to bring together sit-in organizers from states throughout the South, which she then convened at her alma mater, Shaw University, in Raleigh, North Carolina. More than 300 students attended, and the event resulted in the birth of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—a group that went far in reinvigorating the civil rights movement.

While King’s appearance at the conference generated excitement, it was Baker, the 57-year-old veteran organizer, who would nurture and guide the young people. As Ransby writes, “most of the student activists had never heard of Ella Baker before they arrived. Yet she, more than King, became the decisive force in their collective political future.” Baker was protective of the young peoples’ independence, and she advised them to form their own group, rather than being subsumed under an established organization that might limit their fearless creativity. At the same time, insisting that their vision must be about “more than a hamburger,” she encouraged them to expand their movement from a limited collegiate drive to end segregation at lunch counters into an arm of the larger freedom struggle.

Baker subsequently became a mentor to countless young activists, including Diane Nash, Bob Moses, and Bernice Johnson Reagon. James Forman, a key leader in SNCC, has argued that without Baker, “there would be no story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.” Her organizing philosophy became that of SNCC youths who, in places such as rural Mississippi, looked for leadership not in upwardly mobile professionals, but in sharecroppers and domestic workers.

Over the course of its first year, SNCC members debated whether to continue to focus on nonviolent direct action or move toward long-term community organizing, and the group threatened to split over the issue. Baker counseled against the divide, and SNCC came to embody both traditions. Its young organizers contributed to confrontational mobilizations such as the 1961 Freedom Rides—in which interracial groups boarded buses to challenge segregation in interstate travel—and the appearance of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City, where the group challenged the legitimacy of its state’s all-white official delegation. At the same time, many of SNCC’s organizers moved to small towns in the South to engage in base-building efforts and found participatory Freedom Schools that would foster local activism for years to come.

Today, Baker’s example challenges us, as Ransby puts it, “to strike the balance between mass mobilizing and organization-building; between inclusivity and accountability; and between strategic actions and spontaneous ones.” Perhaps more than with any other leader, an effort to honor her life and philosophy is not a move to canonize a saint that we might regard with awe, but rather an affirmation of a democratic endowment we hold in common: namely, the ability of all people to join in the fight for their own freedom.

___________