A review of Ready for Revolution by Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture).

Published in the March 2004 issue of Z Magazine.

Late in 2003, a collection of Martin Luther King’s papers scheduled for auction was opened for public viewing in New York City. Among the most interesting items in the exhibit was a telegram sent from Malcolm X in June of 1964. Malcolm and Martin have long been considered to embody two impulses within the civil rights movement, and the telegram put the split on sharp display: “We have been witnessing with great concern the vicious attacks of the white races against our poor defenseless people there in St. Augustine, [Florida,]” Malcolm X wrote to Dr. King. “If the Federal Government will not send troops to your aid, just say the word and we will immediately dispatch some of our brothers… The day of turning the other cheek to those brute beasts is over.”

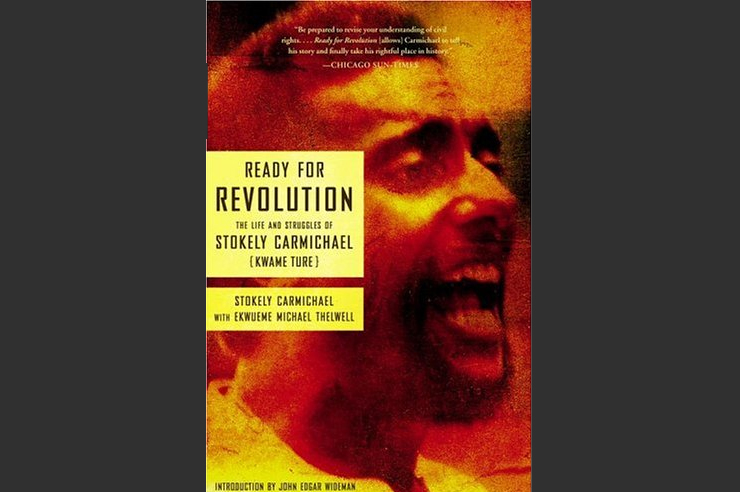

Many would dispute the idea that nonviolence had been exhausted in 1964. But within a few years, a new generation of civil rights activists would move to the forefront, advocating a distinctly un-Gandhian brand of militancy. Chief among them was Stokely Carmichael, whose autobiography, Ready for Revolution, was just published—five years after his death—with the help of his friend, the writer Michael Thelwell. The book shows several reasons why Carmichael is a leading figure in the movement’s transition. He braved some of the most dramatic and resolutely nonviolent actions of the early 1960s, yet later ushered in a new era of “Black Power.” Ready for Revolution makes a significant contribution to the U.S. civil rights literature by providing inside perspectives on how the movement’s organizing changed dramatically in only a few years. But ultimately it does little to account for how “Black Power” affected the collapse of Carmichael’s own organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Understanding Carmichael’s significance in the movement first requires clearing up several misconceptions. The mainstream media used the activist as a convenient peg on which to hang everything that suburban white America had to fear about African-American militancy. Critics blamed his inflammatory statements (“When you talk about black power, you talk about bringing this country to its knees… of building of movement that will smash everything that Western civilization has created”) for the riots that shook cities from Detroit to Newark—uprisings that clearly reflected deep social tensions, not the speech-making of a single individual.

Even the stories that have defined his image within activist circles are often off-base. On the organizer’s behalf, Thelwell convincingly argues that Carmichael’s infamous sexist remark (answering “prone” to a question about the place of women in the movement) was a joke taken out of context. Mary King and Casey Hayden, the supposed targets of the quip, defend Carmichael as being one of the men in SNCC most sympathetic to their criticisms of patriarchy within the organization. Similarly, mention of how white organizers were kicked out of SNCC during Carmichael’s leadership should not overlook the fact that he opposed the move, and that he was consistently critical of the extreme black nationalist staffers in SNCC’s Atlanta office, who, he argued, could not effectively mobilize their communities.

Ready for Revolution devotes some 800 pages to the task of debunking popular misconceptions and giving a picture of who Carmichael actually was. Given the bombast that characterized his most famous speeches, the book is surprisingly measured and conversational. Made up largely of Carmichael’s recorded oral recollections, edited by Thelwell, it provides a detailed context for his evolution as an activist.

Carmichael spent the earliest years of his life in Trinidad, surrounded by his aunts and matriarchal grandmother. At age eleven, however, he was brought by his parents to New York City. As a student at the prestigious Bronx Science High School, Carmichael was influenced by watching the Garveyite soap-box speakers in Harlem, and he befriended Gene Dennis, son of a well-known Communist Party USA figure. But his real political formation came when he attended Howard University. There he quickly rose to the leadership of the Nonviolent Action Group (NAG). As he writes of the civil rights activists, “It was a lot like finding a long-lost family that you hadn’t previously known about, but with whom you instantly recognized your kinship.” Impassioned discussions about politics frequently kept students up through the night (“NAG folk would argue with a sign post,” Carmichael says) and forged deep ties.

In 1961, as an affiliate of SNCC, Howard’s NAG sent activists to join the Congress on Racial Equality’s (CORE) 1961 Freedom Rides to integrate interstate bussing. At 19 years of age, Carmichael was one of the two youngest riders to be jailed in Mississippi’s infamous Parchman Penitentiary. Veteran activists would later recall the horror and pride they felt when seeing Carmichael writhing on the ground and singing “I’m Gonna Tell God How You Treat Me” as punitive prison wardens used metal vises on his wrists to force him to give up a mattress, one of his jail cell’s few amenities. At the same time, SNCC chairman John Lewis would write in his own autobiography that Carmichael showed “not much interest in Gandhi or the principles of nonviolence or even the Bible.” In contrast to many others in the community, Carmichael viewed the actions tactically, rather than through a religious lens. “For me and most of my friends,” he writes of nonviolence, “it was merely a valuable if limited strategy.”

In the early years after its 1960 founding, SNCC, like Howard’s NAG, was a tight-knit, interracial group of young activists. As scholar Clayborne Carson relates, SNCC quickly gained the reputation of being the “shock troops” of the civil rights movement, willing to work in the most dangerous areas of Mississippi, and pioneering new forms of nonviolent protest. Committed to on-going organizing, SNCC criticized Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) for creating “massive, temporary mobilization and press agentry as opposed to creating powerful organized communities capable of sustaining political struggle.” Carmichael writes: “Here comes SCLC talking about mobilizing another two-week campaign, using our base and the magic of Dr. King’s name. They are going to bring in the cameras, the media, prominent people, politicians… turn the place upside down, and split.”

Carmichael graduated Howard and moved south to become a full-time SNCC staffer in 1964, shortly before Bob Moses launched the historic Freedom Summer campaign. Freedom Summer was different from previous efforts because it imported hundreds of young activists from the North to work on dangerous voter registration drives. Moses picked Carmichael to lead the mobilization in the crucial Mississippi Delta. “It’s not just political sophistication” that was required, Moses relates in a quote that Thelwell includes in the book. It was “a feel for the common person which allows you to… really be accepted by them… But you could have that and not have the ability to work with the white northerners…. Stokely was able to move back and forth among all those levels.”

While Freedom Summer was a great success—culminating in the dramatic appearance of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegation at the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City—it also created organizational problems for SNCC. Carmichael writes, “SNCC now had a heightened presence and visibility nationally. As a result, the organization would soon be confronting unfamiliar problems of growth and affluence… Overnight the staff—which means the organization—was fixing to double in size.” He adds, “SNCC could never go back to being the organization/family it had once been or perceived itself to be.”

The growth in the organization also created an ideological opening. Many of the newer staff members, most vocally represented by SNCC’s Atlanta Project, did not share the organization’s earlier commitment to disciplined nonviolence and questioned the goal of integration. In 1966 the growing tension led to the first-ever contested battle for SNCC’s leadership positions. After a prolonged dispute, John Lewis, a religiously oriented activist who led the organization’s participation in the White House Conference on Civil Rights, was ousted as SNCC’s chairman. Carmichael took power. Although he personally opposed the Atlanta group, his candidacy was bolstered by the fact that he had organized the Lowndes County Freedom Organization in Alabama in 1965, an all-black political party that later became the inspiration for California’s Black Panthers.

Carmichael himself is critical of civil rights histories that suggest a sharp divide between the early “beloved community” period of SNCC activism and the later “Black Power” phase. He contends that “the new direction was simply a necessary response to current political realities.” For Carmichael, the transition may well have appeared natural and inevitable, in large part because he had long argued for a move away from “the pain-and-suffering school” of nonviolence. But lack of reflection in Ready for Revolution about Carmichael’s own choices, given the particular circumstances of the time, has two consequences: On the one hand, the organizer likely does not give himself enough credit for his insight and influence as a leader. On the other, the book lacks an honest defense of his most controversial political decisions.

It was during Carmichael’s leadership of SNCC that Ebony editor Lerone Bennett, Jr. would dub him “the architect of Black Power.” Carmichael states that after publicly championing the use of the phrase, he “spent his entire term as chairman doing little else but defining” it. He contends, both here and in earlier books, that Black Power is not a call for separatism. Rather, he explains, “this was simply about the power to affirm our black humanity… and to collectively organize the political and economic power to control and develop our communities… Being pro-black didn’t mean you’re anti-white.”

Carmichael brought several significant insights to his analysis of the concept, including the need for the civil rights movement to shift its focus from the rural South to the ghettos of the urban North. Along with this geographical move, he worked to popularize the concept of institutional racism. “When unknown racists bomb a church and kill four children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society,” he wrote. But when “five hundred Negro babies die each year because of a lack of proper food, shelter, and medical facilities… [society] pretends it doesn’t know of this situation.” Finally, he struck a powerful cultural chord. Carson quotes Bennett writing, “it was the genius of Stokely Carmichael to sense the mood gestating in the depths of the black psyche and give tongue to it.”

However, Black Power also caused serious problems for SNCC. Many mainstream civil rights leaders condemned the use of the phrase. Although Martin Luther King would not join them in denouncing SNCC, he immediately saw the organizational consequences that would come from the rhetorical positioning. He pointed to the political limitations of organizing only in majority-black communities and he also contended that, no matter how much explaining Carmichael did, Black Power would always carry a charged connotation. Unlike “black consciousness” or “black equality,” King argued, it would bring overwhelming media condemnation, alienate liberal funders, and fracture alliances with unions and other supporters.

In Ready for Revolution Carmichael admits that “Dr. King’s judgement about the ‘unfortunate choice of language’ proved to be prescient and, if anything, understated.” But at the same time, he does not take responsibility for his choices, opting instead to blame the media for its predictable overreaction. Similarly, he expresses shock in his autobiography that mainstream civil rights organizations distanced themselves from SNCC. But at the time he fashioned his politics to alienate those very organizations in order to reorient the movement in a more radical direction.

A key example of this contradiction is in Ready for Revolution’s description of the planning for the 1966 Meredith March in Tennessee. “The notion of ‘taking over’ or even ‘leading’ the march wasn’t in our thinking,” Carmichael states in the autobiography. “All we wanted was to give it direction. I honestly couldn’t think of any valid… reason why all the organizations couldn’t participate amicably.” However, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Bearing the Cross, civil rights historian David Garrow cites several earlier interviews in which the activist claimed to have purposefully driven out moderate representatives of the NAACP and the Urban League. “We wanted to pull [Martin Luther King] to the left,” Carmichael argues in this earlier account. “Once we got rid of the right wing completely, King would have to come to the left.” The moderates “fell completely into the trap and stormed out of there.”

It is disingenuous for Ready for Revolution not even to acknowledge the changed position. By neither defending nor rebuking his earlier strategies, Carmichael leaves a less useful guide for present-day activists. Under his leadership, SNCC abandoned militant nonviolence and failed to consolidate its organizing program. It would collapse completely within a few years. It is impossible to say in hindsight what decisions might have altered this fate. However, it is possible to compare SNCC with other models of the time. While Carmichael is right to argue that some change in civil rights strategy was inevitable, SCLC was also pushing for a shift to the North. Furthering their role as the “shock troops” of nonviolence, SNCC activists might have used dynamic urban direct action to highlight economic injustice and institutional racism. Instead, such creative actions were largely missing in the new stage of the movement, especially with SCLC weakened after Dr. King’s death.

Carmichael briefly served as a spokesperson for the Black Panther Party, but he observes that the organization’s lack of organizing experience and institutional memory limited their ability to form lasting structures. This weakness was exacerbated by the media firestorm and the government repression that followed the Panther’s highly visible promotion of armed self defense. Lacking effective organization, in SNCC or in the Panthers, those radicalized by the rhetoric of Black Power were largely unable to carry forward the momentum of the earlier civil rights movement.

While Carmichael was only SNCC Chairman for one year, he remained a popular speaker and media personality throughout the late 1960s. By the time the press spotlight faded, he had moved to Africa. There he took the name Kwame Ture and devoted the rest of his life to organizing for a form of Pan-African socialism. Most of the African revolutions that he supported collapsed under the pressure of foreign intervention and neo-colonialism. Ready for Revolution does not provide a very useful perspective on these events. The book’s view of fallen martyrs in Ghana and Guinea lacks any critical distance, leaving the reader wishing that Ture had applied the same level of constructive scrutiny to African leaders as he had to SCLC.

Kwame Ture always considered himself first and foremost an organizer. While finally succumbing to cancer in 1998, he maintained an admirable lifelong commitment to anti-racist politics. Documenting this dedication, Ready for Revolution will stand as a significant historical resource. But in failing to fully reckon with Ture’s own role at a pivotal movement in civil rights history, it leaves a key story untold. Organizers of the future will miss having a more probing reflection on critical times.